Mia Rosenthal’s exhibition Earth, sky, present, past, is small and modest but enormous in scope. In just eight ink drawings, she explores humanity’s habits of observing the world around us — earth and sky — using drawing as a way to order and grasp at understanding and see connections between our present and the past.

The first three works present a celestial model of understanding the world, referencing how humans have always looked to the stars and the sky in order to understand their place in the universe.

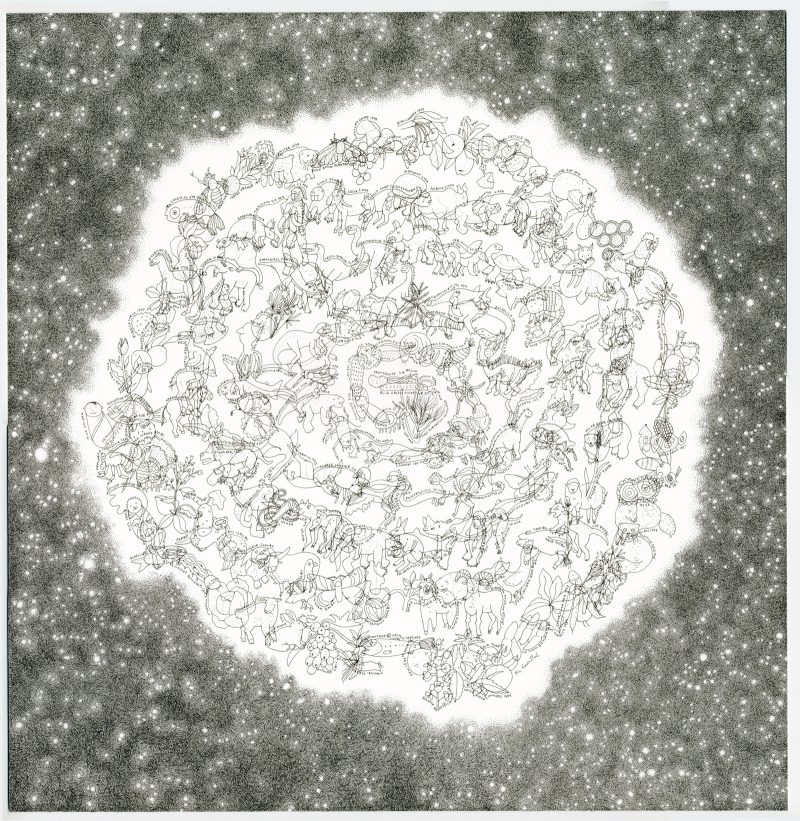

“Life on Earth” presents a cluster of carefully-labeled Earth species circling in a spiral, connected to each other, on a bright gaseous planet or star surrounded by tiny points of light in a roiling gray sky. Looking closer at this tondo-like piece, you see the incredible detail and craftsmanship at Rosenthal’s command: each plant and animal is rendered in thin black ink, while the hatched and stippled sky surrounding them must be the result of infinite patience and faith in one’s steady hand. Rosenthal jumbles together the past and present, placing dinosaurs and prehistoric mammals right alongside recognizable pigeons and sheep, allowing us to take in the grand sweep of evolution and history in a single glance.

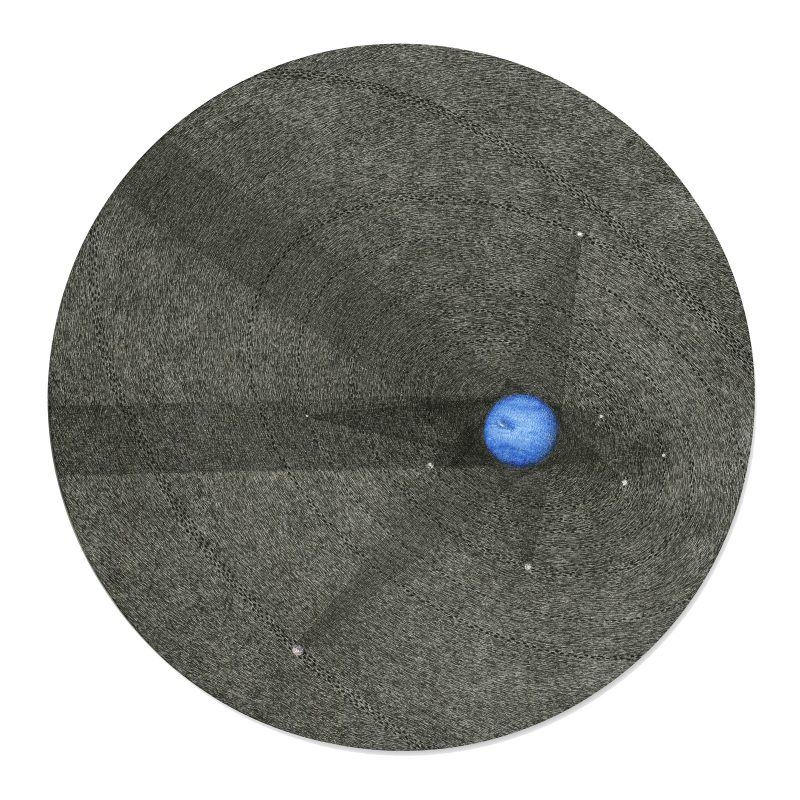

The artist suggests inter-planetary connections in two round drawings that form a vertical diptych. At the top, “Gravitons: Neptune and Moons” shows the blue planet rendered in blue ink against that velvety, densely drawn sky. The eponymous moons are only marginally larger than the negative-space stars, and are linked to one another in a warped star-shaped pattern by virtue of darker sections of mark-making. “Collider,” at first blush, is a more empty composition: like a spherical value drawing you do in art class to learn how shadows work. But stepping back, you see the inclusion of a dark ring drawn outside the edge of the round composition, creating two concentric circles. The drawing’s effect, especially mounted within the round, white frame, is that of a telescope lens, like “Collider” is a representation not just of the sky, but of how humans can observe and study the sky–with a telescope. The piece’s title nods to the Large Hadron Collider, which allows scientists to simulate the first seconds after the Big Bang created the universe.

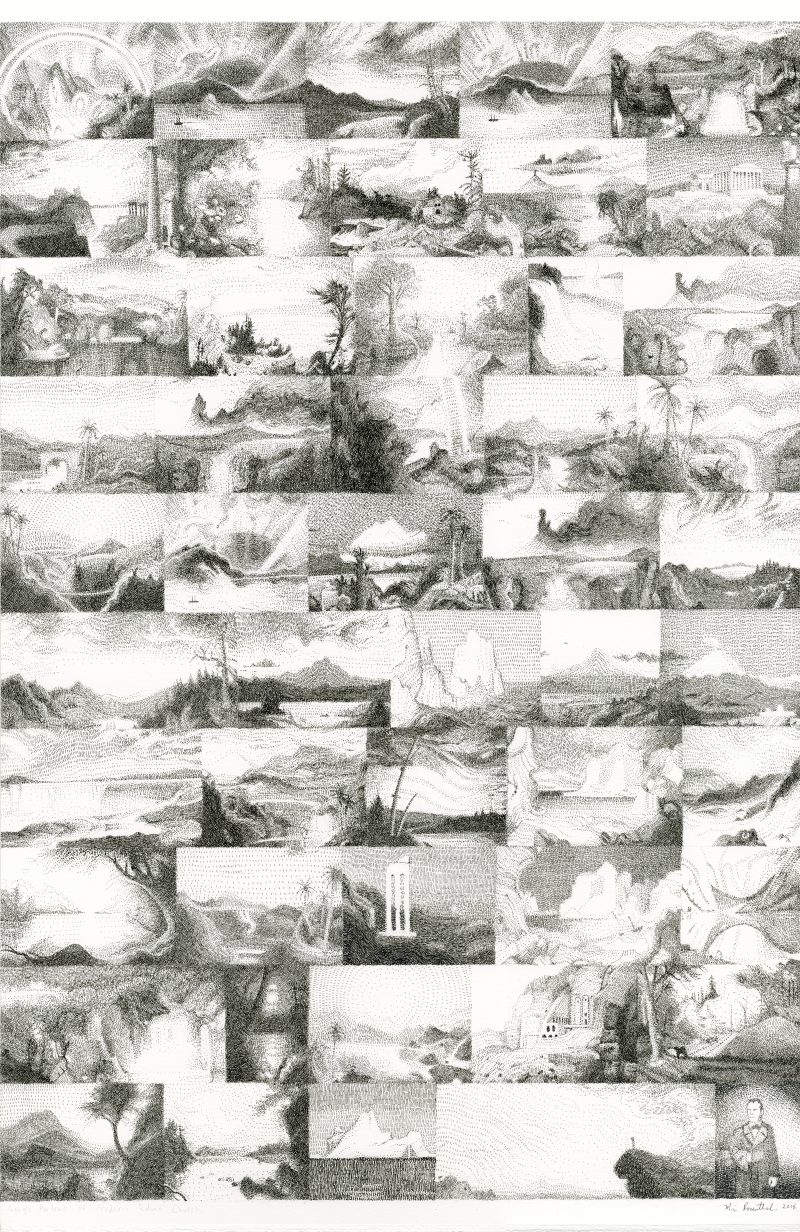

Pointing to our search for answers as a technological one, Rosenthal focuses on the human in “Google Portrait of Frederic Edwin Church.” The grid of thumbnail drawings presents Church’s famous landscape paintings as tiny adjacent squares and rectangles, all rendered in impossibly minute strokes of ink. While useful, few things look as banal as a page of search-engine image results, but Rosenthal makes them beautiful. Beside “Frederic Edwin Church” is a two-sectioned drawing, neatly divided in half left and right, but with both on the same sheet of paper. “Google Portrait: Paleolithic Cave Painting/Hubble Telescope” presents on the left the horses of the cave paintings of Lascaux as one small drawing after another in a crowded grid of search engine results. Paired with the overwhelming grid of cave painting thumbnails, the right side image of the sky seen through the Hubble Telescope is positively holistic and calming. Is the artist suggesting that you sacrifice the whole for an infinite number of parts, or, in other words, miss the forest for the trees?

The mystery with this particular work: why are these two drawings on the same piece of paper? What is Rosenthal telling us by showing us Lascaux and Hubble, side-by-side and inherently connected? The paleolithic paintings of horses are considered to be some of the earliest works of art ever created by humans, while the Hubble Telescope is a model of science, created by humans and used to explore the stars. Both grew from humankind’s wish to understand its surroundings and its place in the universe. It might be a stretch of interpretation, but I can’t help but think of how light travels in space: how the stars and the planets that we can see on Earth are actually how they looked millions of years ago, because of how far away they are from us. Looking at the stars is like traveling through time; similarly, looking at the works of art in ancient caves is a way of traveling through time to an earlier human era.

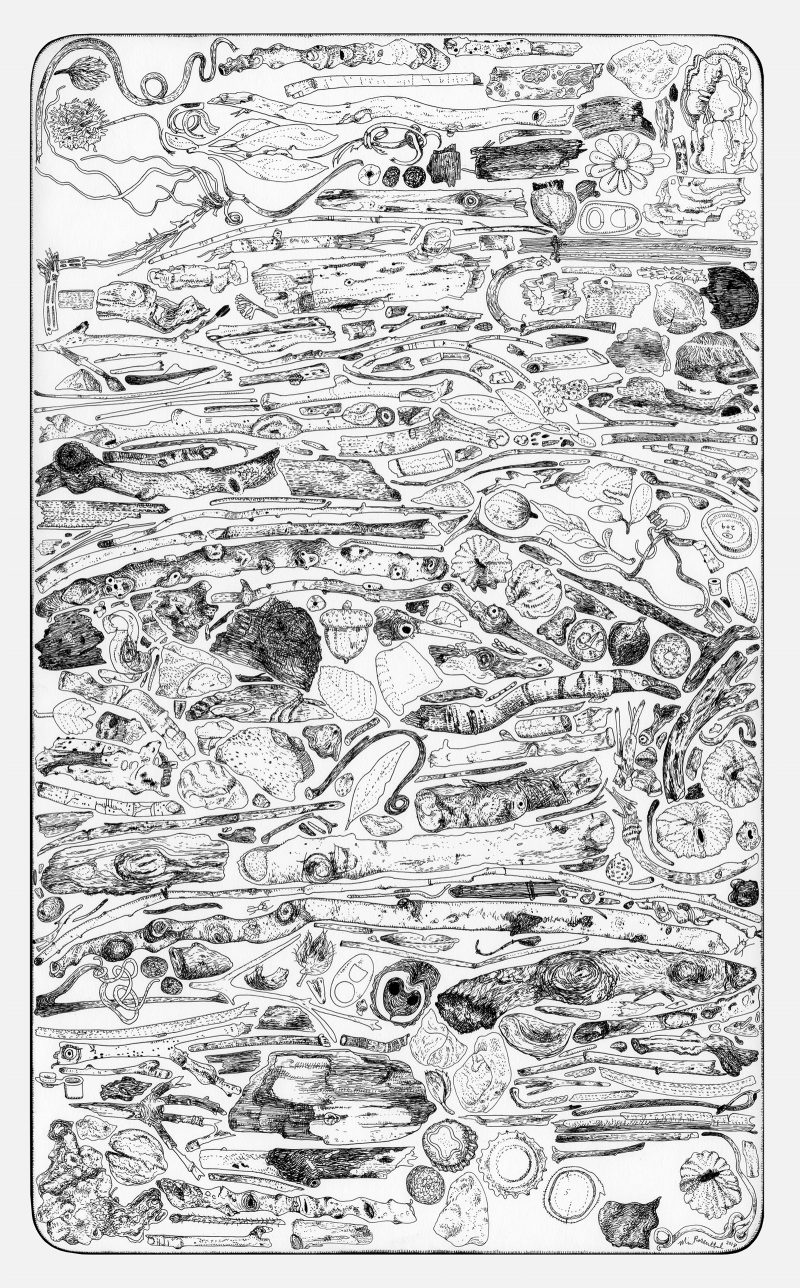

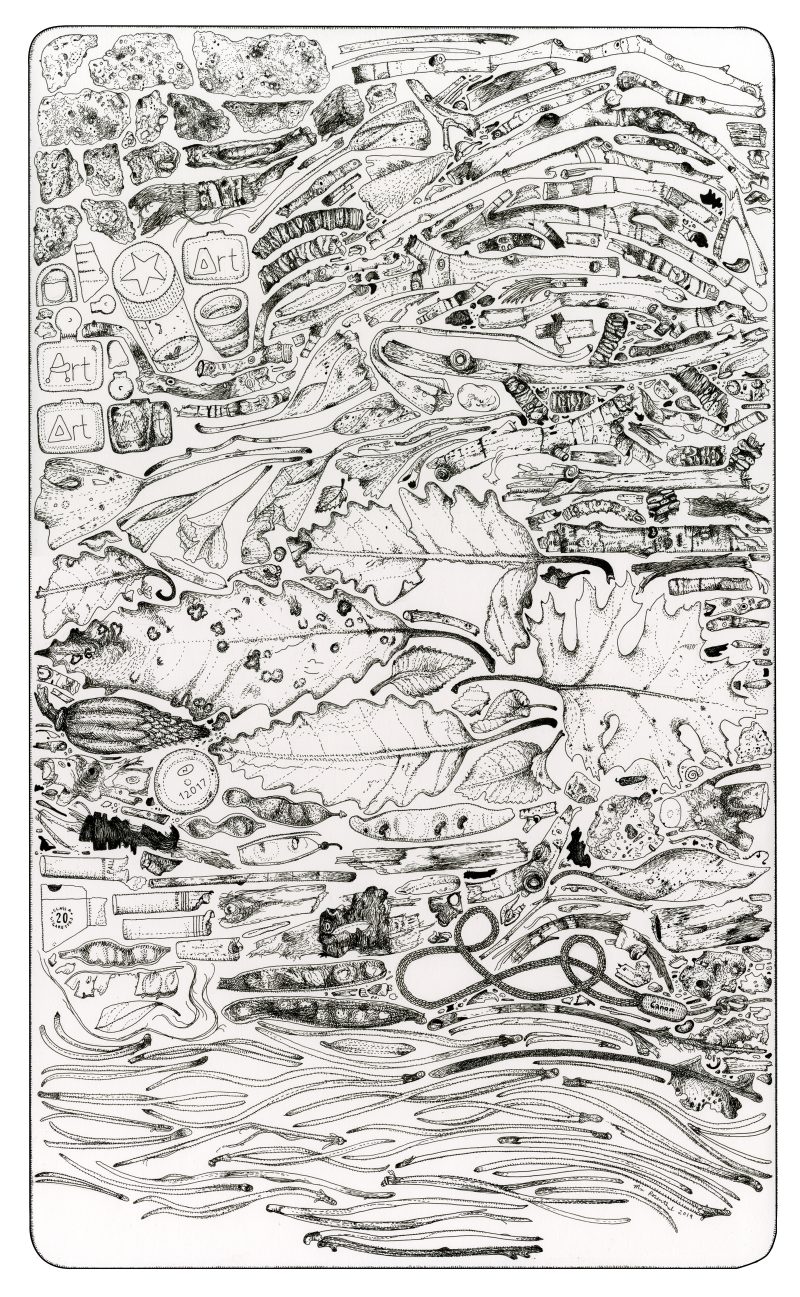

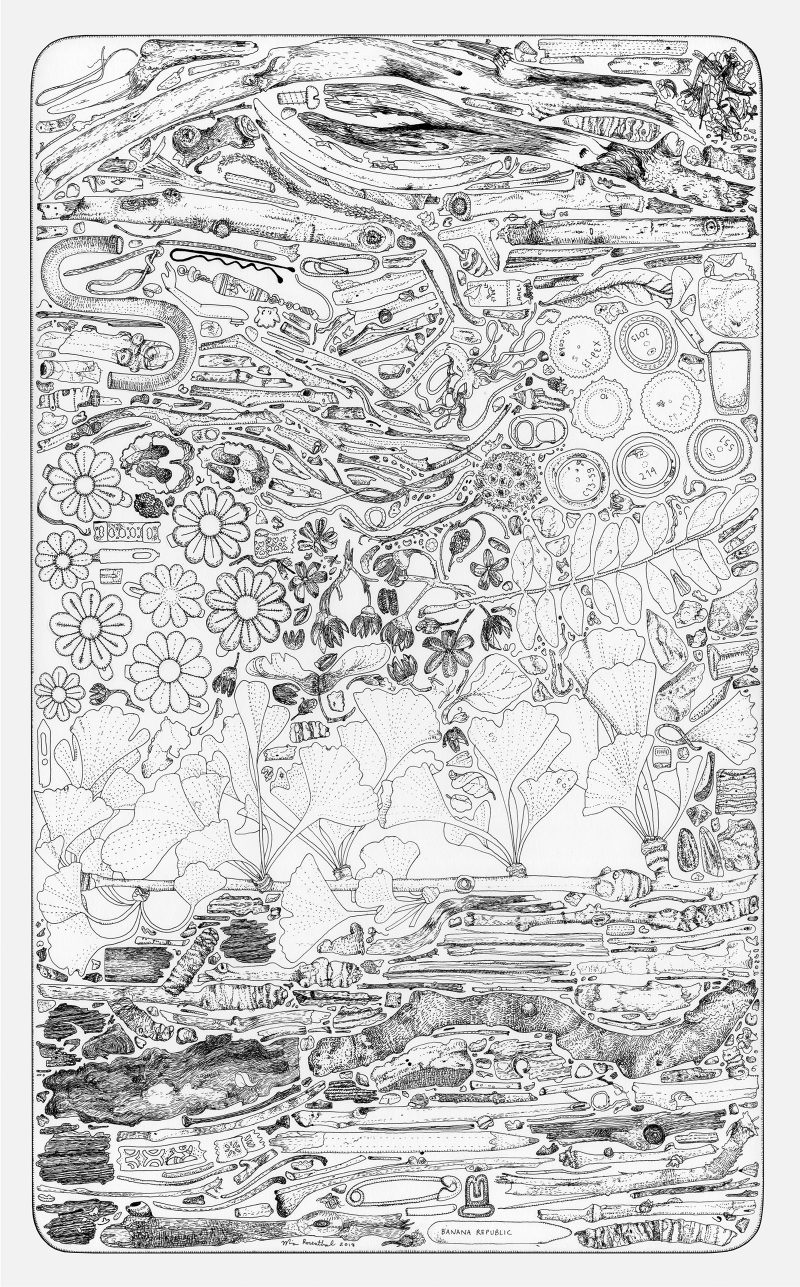

While some of the works in the exhibit deal with macro, big picture issues, some delve into the incredibly specific — like trash found in Philadelphia. We’ve traveled from looking at the sky through naked eyes, through a telescope, and into looking for answers with the internet: In three works rooted in the specific instead of the general, Rosenthal observes and draws the found objects in particular Philadelphia locations. The linework in “Found beneath the Septa Railroad Bridge,” “Found outside the Philadelphia Museum of Art (west steps, winter),” and “Found at Mt. Airy Playground” is bolder, more sustained, and less fuzzy than in the previous works, snapping the detritus at these three spots into perfect clarity. So what can we learn from the things Rosenthal found on the ground? “Septa Railroad Bridge” consists of mostly twigs and rocks–natural outdoor/landscape remnants–intermingled with the occasional Coke can opener tab, a flower hair clip, bottle caps. “Philadelphia Museum of Art” balances the natural and manufactured materials, juxtaposing large leaves with the museum’s small metal admission badges, while “Mt. Airy Playground” is more evidently cluttered with litter: amidst the gingko leaves are paper clips, keychains, a Barbie doll’s arm, a razor blade, and a repeat of the bottle caps and flower clips of the adjacent drawing.

Everyone looks at the sky; many people use Google Images; some people enjoy cave paintings, but no one looks at the crap left on the ground. With the final three drawings, Rosenthal honors her home of Philadelphia, creating an orderly taxonomy of the things that no one looks at, devoting as much detail and attention to trash as to starry night skies.

“Mia Rosenthal: Earth, sky, present, past,” GALLERY Land Collective, 57 North Second Street, Philadelphia PA, June 7 – July 5, 2019

More Photos