[EDITOR’S NOTE: This essay was originally published on Dec 12, 2018. It was the grand prize winner of the 2018 Artblog New Art Writer’s Contest! Keep your eyes peeled because this week, we announce the 2019 winners!]

Chaim Soutine and I Have Never Broken a Bone

By Talia Gordon

Earlier today I burnt my thumb on the handle of an omelet pan whilst pulling it from beneath the broiler. My left hand which is, incidentally, the hand with which I write — now, a round and translucent blister at the base of the first joint, pressed beneath the barrel of a pen, flattened to an ovoid form, uniformly white and uniformly painful. I write anyway, and it feels as though I am consciously reducing my hands to a greenish flare of nauseous pain.

At the Barnes I spend more time in front of Soutine than anyone else. I grow tired of Renoir, often, nonspecific and blurring into dreamlike familiarity; I have never been fond of false advertising. Hands do not advertise falsely. Hands, in Soutine, break in a thousand different ways. They curve wildly, both at and straying from the knuckles, as though they were slammed in a door a couple dozen times over. A half-dozen tortured hands at a time, I wander the museum staring just above the knees, watching fingers flit from place to place, unshattered or unbroken or squared or narrow, but, regardless, signs of an unaltered world, an upheld equilibrium.

Chaim Soutine was born in Russian and lived in France. I know no French; I cannot read the titles of his work except in half-remembered Spanish cognates. A language tortured into new shapes, slammed in the screen door of borderlands or Navarr or Aragorn or whatever contemporary kingdom ensured isolation. Russian I understand abstractly, or specifically, but nothing concrete. The Cyrillic alphabet looks to me, sometimes, like hands turned at oblique angles, the heft of my anglicized д, or the maimed linearity of the cursive ж, or my complete inability to differentiate between ш and щ. I think you can see a language in gesture, in the way fingers contort themselves into lettered things, complying only with the fixed rule of jointedness. There are more cognates than one might imagine.

In Modigliani portraits, Soutine has straight fingers, somewhat stubby or blunt, at any rate. Unbroken except, perhaps, the ring finger of his right hand, which curves oddly into some facsimile of a religious symbol I have never seen. No source can tell me if Soutine was right or left handed, but I like to imagine him using his left, now, a small white blister at the first knuckle of his thumb which he must take care to avoid with the handle of his brush. I imagine that, once, he presses too hard and lets go immediately, and this it is the mistake that creates a break in the third finger of some subject. That some physical pain can create corresponding metaphysical pain which I, now, can see; which I, now, feel in my hands as I wander without aim. Wandering through Europe, desultory, through languages. Through borders and back again.

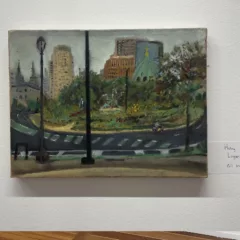

Interestingly, Soutine had intimate knowledge of bones. He painted them with some regularity, harbouring the half-rotted carcasses of animals in his studio until the neighbors complained of his audacity, of the smell, of the ensuing thirteen point eight million dollars a painting in this series would demand long after its artist’s death. Interestingly, the Barnes also houses a painting from this period, entitled “Le Lapin écorché,” which is to me a rabbit, scorched, burned to bone and cinder, though the title translates to “Flayed Rabbit.” I imagine Soutine, knowing the shape of a hand, the skeleton, the joints and the metacarpals and whatever else I once knew but he certainly did, and laughing as he misshapes them, deliberately, making both real and unreal the horrifying pain of a body made to burn.

I heard once that, in dreams, our hands change shape. The number of fingers shifts while we watch, settles at eight or nine, becomes a bear or a horde of snakes or the bunny I fed as a child, hopping into some unidentified distance for dissection. The blister on my thumb reminds me of this, sometimes, that these hands can be only my hands and that only I can be waking and wandering, that this nightmare belongs to me and only to me. I, too, have intimate knowledge of the bodies of animals, though disjointed, from years of science education; I have held a hundred cow’s eyes in my hands. A friend of mine’s job one summer was to sort through lab mice and cut out their ovaries and I like to listen to her talk about it late at night, when I cannot bear to look down, to know if my palms are becoming snakes somewhere I cannot see. I think Soutine knew about the hands, and the snakes, and the rabbits. That no painting should have living hands.

Tonight, when I dream, I will meet with Chaim Soutine once upon a time, in some blandly European countryside abounding with rabbits and disarticulated languages kept from one another, but it will not bother us. We will speak with our hands alone, eight fingers in new configurations like the Cyrillic alphabet, but with more letters. Across the field, where the grass has gone yellowed and dry, the great inferno of hell will have opened, billowing like wildfire, out and out. Our fingers will become snakes, and we, too, will recognize ourselves, and in that moment I will wake, gasping, somewhere beneath the yellowed walls of the Barnes Foundation. It will still stink of sulfur.

Talia Gordon is a sophomore at the University of Pennsylvania, where she studies English, Art History, and Russian. A poet and an essayist, Talia has long loved creative writing, and she looks forward to continuing and improving her work in the future. She is deeply interested in art, language, and the ways in which they connect and impact one another, particularly in the context of public and private spaces. She is also interested in hiking, skiing, and surviving the semester. She can be reached at gtalia@sas.upenn.edu.