Wenlu “Lulu” Bao came to the United States two years ago as a student at The University of the Arts, Philadelphia. She graduated in Museum Communication with the Highest Academic Achievement Award, and went on to take up several roles as an art professional in the States. But even today, seeing a kit of pigeons take flight in Center City, Philadelphia — where the curator lives — would have her feeling for a second that she was back home. “They are exactly the same birds that I used to see everyday in Shanghai,” remarks Wenlu, curator of the show ‘Mind the Gap’ featuring six female Chinese artists, in The Delaware Contemporary.

When Wenlu was assigned to curate the show in 2018, one of the first things that she zeroed in on was the title, Mind the Gap. She was struck by a memory from years ago, when she had just stepped out of a subway in Shanghai and seen the words ‘Mind the Gap’ on the pavement. It was a warning to be careful of what’s in front, to avoid an obstacle. Metaphorically, obstacles can be feelings of insecurity, vulnerability, fear, discomfort, depression, inaccessibility, etc. Obstacles create gaps. Through the voice of Chinese female artists, Wenlu wanted to throw light on these gaps — be it geographical, cultural, or generational.

Wenlu believes that exploring the gaps helps understand our role and identity, and answer the question ‘who are we’?

“Personally, as an immigrant I have experienced a gap in communication when it comes to interaction with friends and colleagues here. There are times I just cannot take part in some conversations, especially about sports. I do believe that casual talk brings people together, it’s the culture here. But I can’t partake in it, I am okay with that,” she says, over a one-on-one chat at the gallery. “More importantly, I think it’s okay to talk about it,” she says.

When Wenlu started working on the project, a senior curator suggested her not to focus the show on topics of immigration, and challenges of being part of a minority, but simply let people enjoy art for art’s sake. But the more Wenlu thought about it, the more she was convinced that owning up one’s identity and talking about it is the only way she could create an authentic show. “Initially, I did think that being part of a minority group, by talking about the gaps in experiences, I was taking advantage of my identity. I was shy talking about my identity before, but the more I worked on the project, I realized that it’s okay to be curious about these gaps. For me, art is not separate from daily life. All the experiences that we have had is part of us,” she says.

An work by artist Meng Du features a flock of glass pigeons that look lost and melancholic. An audio speaker plays the cooing and whistling of the birds, recorded in Beijing. The work suggests the confusions and shifts that are part of the immigration trend. There are millions of South and East Asian immigrants in the United States. While the move is challenging, New York-based gallerist Echo He, (who was one of the panelists at the discussion moderated by Wenlu at The DC), points out that lack of exhibition opportunities and dedicated spaces for Asian art, make it challenging for Asian art prprofessionals to establish themselves here. Echo’s gallery space encourages works of Asian artists.

“Most people outside China still think Chinese art is synonymous with blue and white China patterns, Calligraphy, and old Classic paintings,” says Wenlu, with concern. “With this show, I wanted to show that contemporary art can borrow inspiration from the past, and still remain very contemporary.”

Many of the works in the show use some elements of Chinese heritage and give some glimpses of Chinese lifestyle, thus exposing the past, and using it to embrace the present.

For example, senior contemporary artist LIN Yan creates molds of ancient Chinese bricks using Chinese Xuan paper to create installations akin to the old gateways in Beijing, in the contemporary setting of the museum. Her works graze the subject of modernization and rapid development in the past few decades both in China and the US. Suggesting the impact of westernization are artist Caroline Chen’s series of paintings. This includes one of a family sharing food around a table that is reflective of the Chinese culture, and another of teenagers taking pictures of food on the table.

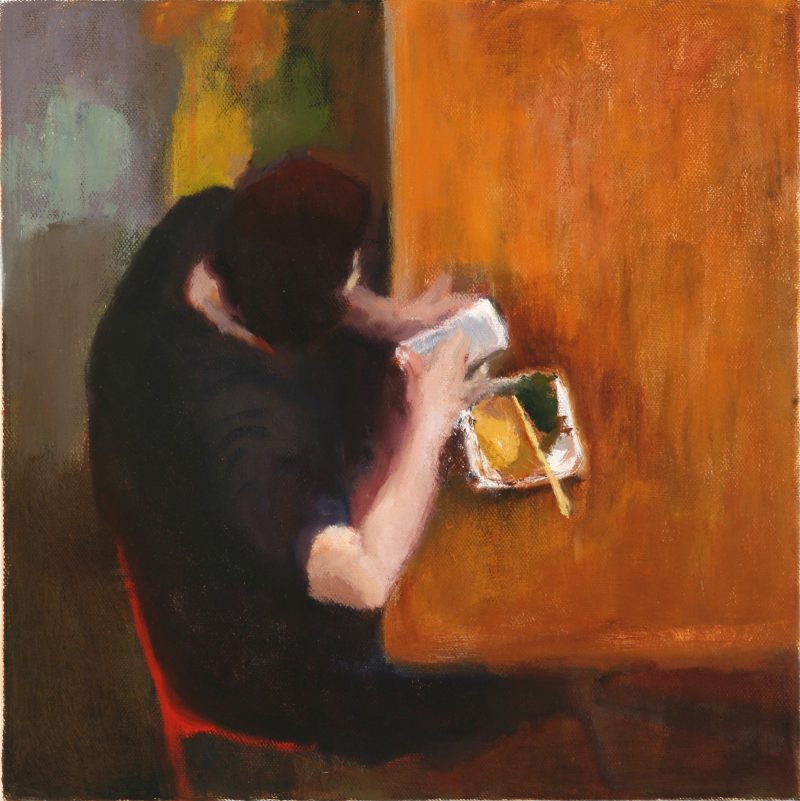

Similarly, artist XIE Kun uses steel lunch box, a ubiquitous object in 80s China, in her works. “Back in the days, you could find the steel box in every home. We didn’t have a microwave then. So we would warm up our lunch box in a bowl of hot water,” says Wenlu. Interestingly, inside all these boxes are pen and ink drawings that depict the artist’s nightmares — nudging us to think about the gaps between real and imaginary; between the feelings of fear and safety.

Be it pigeons or a steel lunch box, for a Chinese immigrant in the States, these are small treasures to connect with life back home. Says Wenlu with a laugh, “But what reminds me of Shanghai the most is an Oreo cookie! It’s funny, since it’s a US product. But that’s the only thing that tastes exactly like the cookie there.” In this case, a small cookie (sold and loved in both countries) in its sweet way, helps bridge the gap.

MIND THE GAP, Group exhibition by contemporary Chinese female artists, November 16, 2019 – January 30, 2020 (NOW CLOSED)