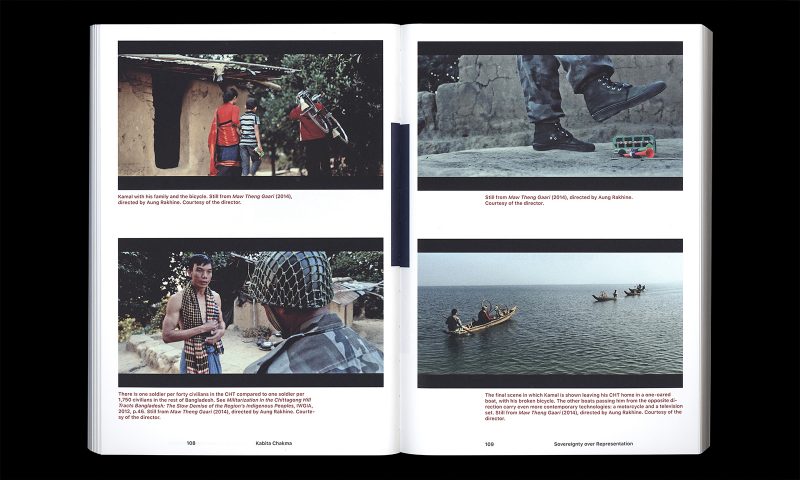

Kate Morris “Shifting Grounds; Landscape in Contemporary Native American Art” (University of Washington Press, Seattle: 2019 ISBN 978-0-295-74536-7

University of Washington Press; Amazon

Kate Morris’s study addresses a group of Native American artists whose work incorporates Indigenous attitudes to the land. In the introduction she enumerates “themes of presence and absence, connection and dislocation, survival, survivance, * memory, commemoration, vulnerability, power, and resistance that surface again and again in reference to the Native landscape.” It is a valuable presentation of a group of under-recognized artists and unites them within a framework that suggests Indigenous knowledge is essential to a more inclusive art history.

* survivance, a term theorized by Gerald Vizenor and used in Indigenous cultural studies, is “an active form of presence,” and rejection of “dominance, tragedy and victimry.”

The role of the land in Indigenous cultures is fundamental to religious beliefs, communal identity, activities and origin stories, and it is this integration of the human with the rest of nature that characterizes the artworks Morris discusses. She brings serious attention a diverse group of artists whose work should certainly receive broader attention: James Lavadour (Walla Walla), Kay Walkingstick (Cherokee), Alan Michelson (Mohawk), Kent Monkman (Fisher River Band Cree) and the collective, Postcommodity.

The artists employ a variety of media: painting, sculpture, installation, video and performance and Morris is sensitive to their uses of their media as inherent to their subject. She describes the evolution of James Lavadour’s monumental, multi-panel paintings built up from many layers of fluid paint. The artist has explained “In paint there is hydrology, erosion, mass, gravity, mineral deposits;” and Morris explores the analogy of Lavadour’s technique with the geological history of the land to which he refers. This is particularly important in his paintings where overt landscape depictions are placed alongside abstracted versions. The artist emphasizes the depth of his association with the land, describing a walk in nearby mountains during which “I realized that what I was looking at and what I was doing were the same thing…. As a physical being, I was an event of nature myself. I could become a conduit for making art, a conduit of nature,..”

Morris discusses the artwork within current ideas about sovereignty in Indigenous cultural studies which should be valuable to readers unfamiliar with the subject. She then turns to visual culture theory, and here I question the utility of her choice. While she notes the concept of “landscape” as a genre of painting (and related, two dimensional art), she wants to extend the term to other genres and formats where the concept has never been employed. Land artists may have created work out of actual land, or documented activities done within a natural environment, but none of that was created or analyzed within a conceptual framework of “landscape.”

In the 1960s Raymond Williams pointed out that the scenery depicted in many eighteenth and nineteenth century paintings was a reference to real estate as much as to nature; these were paintings about ownership, property, and its associated power. This is exactly the concept of land that Morris’ artists reject. Their subject is neither property nor territory but a holistic idea about place, an affirmation of the unity of nature and culture as well as what it has meant for Indigenous societies who have been displaced – usually violently – from their native lands.

The book is particularly well-designed, printed and bound and is fully illustrated in color – a rarity for an academic publication. Its small format (10” x7”) makes it hard to appreciate the visual presence of many large artworks, and for the two-dimensional works details would have been useful to convey some of their surface qualities; but the reality of publishing constraints does not diminish its significant contribution to art history.

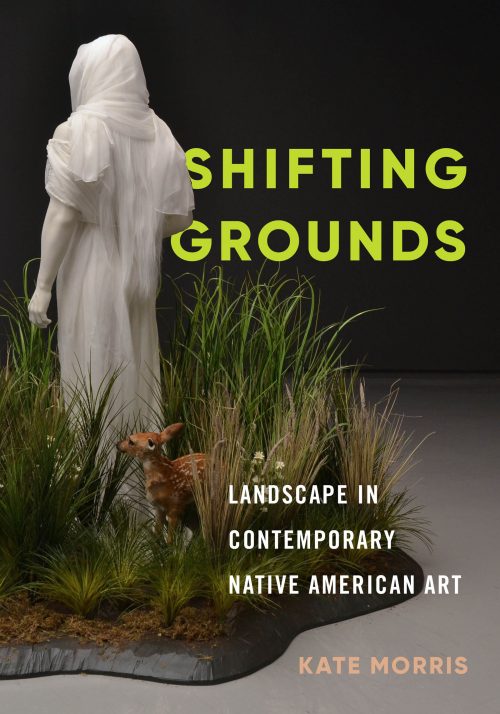

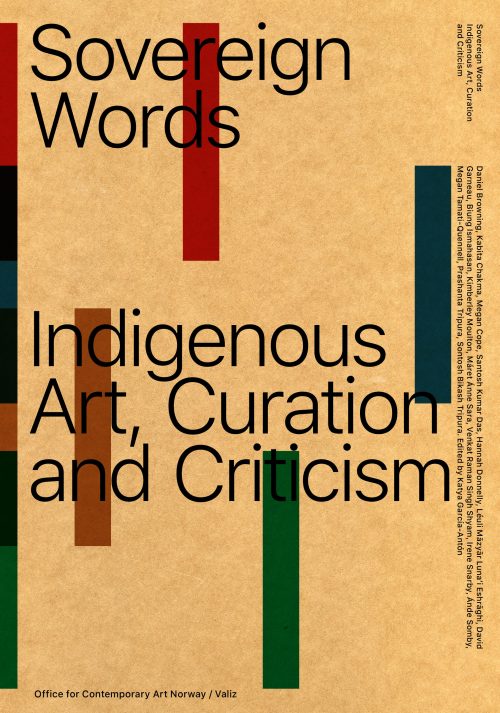

Katya García-Antón “Sovereign Words; Indigenous Art, Curation and Criticism” (Valiz, Amsterdam and Office for Contemporary Art Norway: 2018) ISBN 978-94-92095-62-6

“Sovereign Words” assembles sixteen essays that came out of an international conference that was part of the Office of Contemporary Art Norway’s ongoing project of “Critical Writing Ensembles.” It includes Indigenous writers from four continents and authors include artists, poets, story-tellers, performers, lawyers, curators and scholars. They question whether including Indigenous art within the expanding cannon of World Art gives sufficient agency to their communities; how art that makes no distinction between the visual and performative will be accommodated within a Western concept of art history; and acknowledge the possibilities of risk when Indigenous and non-Indigenous thinkers attempt to bridge their cultures.

In discussing the significance of critical writing about Indigenous art, David Garneau (Métis, artist, writer, curator and professor) refers to writing by non-Natives as “settler texts”and calls for criticism that will be useful to Indigenous Contemporary artists. Garneau sees the concept of an “Indigenous art world” as an extra tribal, global network by means of which artists whose work addresses their own communities can look out for each other.

The curator Megan Tamati-Quennnell (Māori) situates the use of language by four contemporary Māori artists against the colonial development of the written language, the mis-translation of the English version of treaties with the Māori and the agency expressed through tribal newspapers. She demonstrates that a sophisticated understanding of the artworks necessitates a knowledge of how the artists are responding to this history.

The curator and writer Kimberly Moulton (Yorta Yorta) gives a poignant account of her experiences with finding Ancestral belongings in the collections of foreign museums and realizing that she may have been “the first Aboriginal person to connect with them since they were taken.” Biung Ismahasan, curator and writer from the Bunun Tribe of Taiwanese Indigenous peoples recounts how curatorial decisions about siting and presentation of a performance artist incorporated Indigenous artistic practices so that the performance became “an alternative space for Indigenous intervention and cultural sovereignty.”

I know of no other publication that gives this kind of voice to Indigenous thinking across the breadth of subjects addressed.

Check out Part 1 of the review here.