[EDIT: Biggs Museum is currently closed due to Covid-19. Check out a virtual tour here!]

It’s a pleasant March evening, social distancing is yet to become the norm. A group of visitors are gathered at Biggs Museum, DE, to participate in Stephen Althouse’s tour of his large-scale photographic prints. One of the works on display is a close-up of a washboard — a tool that was used in the pre-industrial era to handwash clothes. Its surface is partly worn flat by the countless clothes rubbed on it, over several years and across several generations. Althouse says to the attentive crowd, “It (the washboard) conveys the story of human toil and nobility of humankind — to be able to wake up and repeat the task everyday, till the end of their lives”.

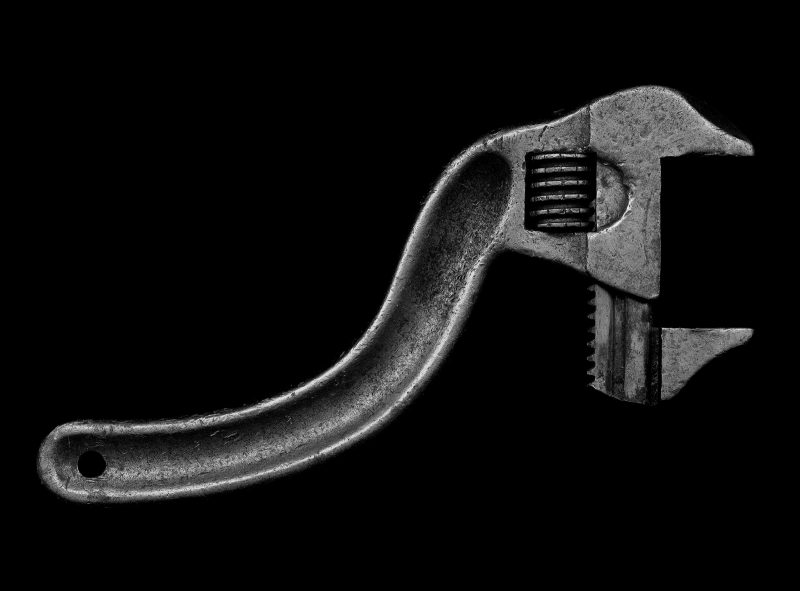

The exhibition includes 36 extremely large, black and white photographic prints, done by Althouse between 2003 and 2017. They are an ode to old and discarded utilities and artifacts that were once part of everyday life, before technology marked them irrelevant. A scythe (replaced today by tractor machinery) and a plumb line (replaced by spirit level) find new lives in Althouse’s images, their status raised from mere tools to monuments that deserve to be preserved and respected for their contribution to humankind. “They (the tools) are a reflection of humanity… a reflection of us,” he says.

The still-life photographs are not spontaneous, but painstakingly contrived and pre-conceived. It takes months, sometimes years for his subjects — some found by chance, some consciously searched for, and some created from scratch — to be frame ready. “It’s a laborious process,” he says. Althouse uses large sheets of film and a large format view camera, “the type you put a black cloth over your head, like in The Three Stooges (short movies),” he says with a laugh.

After development, the sheets of film are scanned, and the digital images are worked on, and often embedded with “secret messages” in Braille using Photoshop. The phrases are not meant to be understood, most are in Latin, 16th century German, Catalan, or Pennsylvania Dutch, but create a sense of mystery. “Like the hieroglyphics on Mayan structures and Egyptian temples,” he says. The final images are printed using a wide format inkjet printer, and are enlarged to up to 9.5 feet in length.

As a child, Althouse never had an inclination to become an artist, just an innocent curiosity for artifacts. He grew up in an isolated farm in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where he recalls playing alone in the barn or the woods by the creek. His house was a 1700s stone building that had hand-hewn beams and timber structures as part of the interior. “I loved observing marks made by hand tools on wood,” he says. Memories of his childhood include collecting rusted metal junk that washed up on the creek and frequent visits to the nearby Mercer Museum in Doylestown — a “dark and cold place that leaked when it rained” and featured tools and artifacts ranging from old chairs to wagons.

In school, Althouse opted ‘shop’ classes over art classes, and learnt to weld pieces of junk metal together to make “unusual non-utilitarian things”. He wanted to pursue a career in the US Diplomatic Corps. However, he had to take up a beginner’s art course, as it was a general college requirement in his junior year. “I found it to be so exciting and challenging that I changed my major to Art,” he says.

To make money for art supplies, he took up jobs in concrete construction, railroad, farming and stone quarry industries. “I went looking for jobs that involved hard labor. I felt that this (hard labor) culture encompasses the majority of humankind around the world, over many thousands of years. I wanted to experience it and get to know people who were integrally a part of it.”

Despite a Bachelor of Fine Arts (from University of Miami), and a Master of Fine Arts in Sculpture (from Virginia Commonwealth University), Althouse was still unsure about making it as an artist. Meanwhile, he had taken up a photography course to better shoot his sculptures, and proved to be successful in teaching photography to students. Uncertain about his career choice yet, Althouse decided to travel to South America.

A pitstop in Miami, which was meant to be for two weeks, turned into four years, when he came across large docked charter boats on an island near Miami beach and decided to live in one. There, rocked by the waters of Biscayne Bay, he contemplated life and humanity, and for the first time imagined himself as a visual artist. A teaching opportunity at nearby Barry University gave him access to a studio, where he created works, but “was still ambivalent to exhibiting it” since he thought they were too personal.

A (Fulbright) fellowship opportunity in Belgium gave him the final push. His nine-month stay was in a small quiet town surrounded by farmland. Since the environment was reminiscent of his childhood home in Bucks County, it brought alive memories of the lazy afternoons he spent collecting old tools. Axes, abandoned wrenches and weathered iron wedges manifested themselves on his rich archival inkjet prints. “I found tremendous satisfaction with my work, and I wanted to share it.” His fellowship ended with a large solo museum exhibition of his works. Althouse finally felt ready to let the world see his art. Since then, his photo prints have been in 35 museum exhibitions (16 solo and 19 group) around the world.

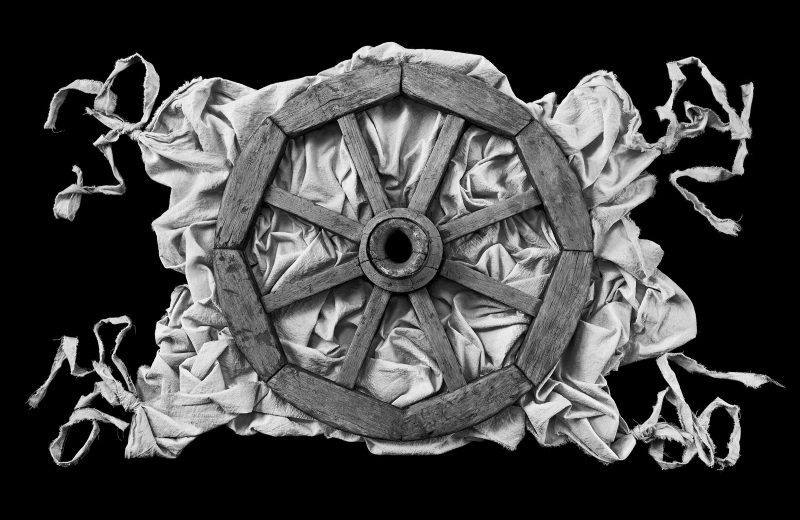

He took an early retirement from the university, and moved from Miami to a peaceful Amish town in Centre County, PA, where he continues to create works inspired from chapters of his life. Here, he discovered the deep and moving funeral hymns of The Ausbund — one of the oldest Christian song books that’s used by the Amish even today — and reflected on the topics of separation and death. 2017 brought with it dark times for Althouse, he lost his parents and sister within a short period. From this sadness and exhaustion, rose a 5×8 ft photo print of a broken Amish wagon — marred, deformed but still standing on its wheels. He refers to it as a portrait of himself during that particular time of his life. Though his works each have a personal story connected with them, Althouse clarifies that they “are not meant to be literal communication, but a stimulus for each person’s thoughts or emotions”.

Given the current times, when the air is dense with loss, fear and confusion, the wagon could well be a portrait of the world. Broken and shaken, but forever resilient.

The exhibition ‘Stephen Althouse: Relics‘ is on at Biggs Museum, Dover, Delaware, till May 24, 2020.

[EDIT: Biggs Museum is currently closed due to Covid-19. Check out the virtual tour below!]