[Ed. Note: This essay and the conversations that sparked it took place prior to the events surrounding the death of George Floyd. Read part two, “Maddie Hewitt talks sustainable art making, and the reality of the climate crisis” ]

I recently had the pleasure of exchanging emails with the Canadian artist Caril Chasens. Our introduction was quite serendipitous: Caril had seen a post by Wit Lopez, former Artblog Managing Editor, on Canadian Art. After learning about Wit’s Artblog connection, Caril reached out, and her email eventually landed with me. This winding procedure, I would come to learn, is not uncommon in Chasens’s practice, as an artist who values freedom and curiosity.

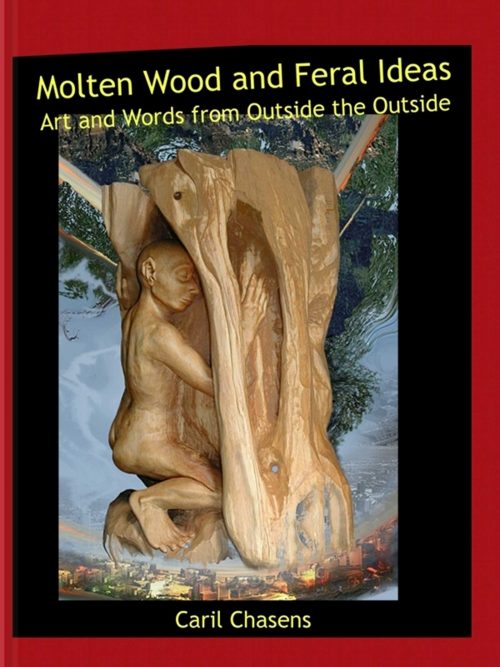

Caril Chasens lives “way the hell up the road” in British Columbia. Perhaps, then, it should come as no surprise that Chasens is so connected to and inspired by nature. Her recent book – Molten Wood and Feral Ideas: Art and Words from Outside the Outside (2015) – teases out this connection in ways that are beguiling, intriguing, and always fascinating. The text is monolithic – reaching almost 200 pages – chock full of images, bits of text, and reflections. From pictures of wood sculptures small and large, to drawings, to digital collages, Chasens is never bound by medium. The text is similarly open: at times it reads as a manifesto, covering topics like idea formation and gender identity. On other pages the words describe or illuminate works of art, or the process of artmaking. Molten Wood and Feral Ideas is, to me, a deep look at an artist who is as difficult to pin down as a will-o’-the-wisp, and who will lead you on an equally as unexpected journey.

One phrase that particularly struck me as I dug into Chasens text is the idea of “the thingness of sculpture” (pp. 7). This phrase, to me, is perfect: “thingness” is at once specific, pointing to an embodiment; and also vague enough to open a multiverse of possibility. In exchanging interview questions with Caril, I found her to thrive in such openness. When asked if she identifies with a certain medium, she said, “from my own point of view – and probably not from others – the damn ideas may be primary. But, yes, professionally speaking, I would say I am a wood carver… But, I value the exploration and range, the ability to evade the limitations of a medium.” I have come to find this statement emblematic of her writing style: direct, but open minded. Though I didn’t count the appearances of “damn” within Molten Wood and Feral Ideas, I have a sense that it appears more than a handful of times, as a kind of friendly hype-person punctuating key ideas.

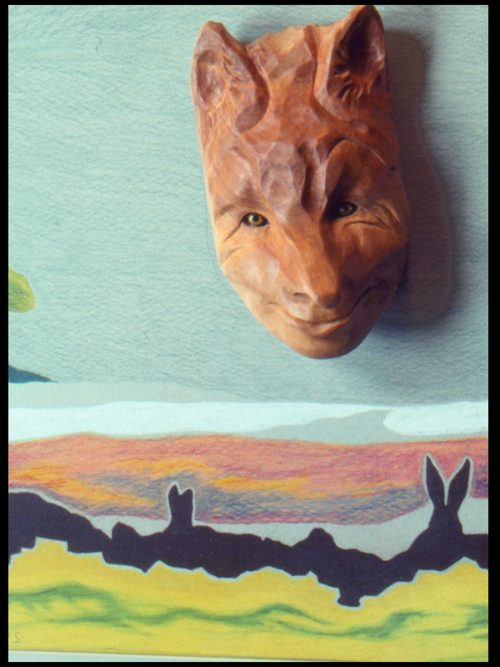

Openness spans her work in other ways, too. Not only does Chasens work across different mediums, but she is also unbound by subject. The pages of her book document the range of her visual imagery: animals like elephants and orcas and horses, nymph-like creatures, landscapes, and sometimes just organic abstract forms. Looking at the work is almost Alice-like: the deeper you go into the pages, the more curious things become. This enchantment seems relatable to Caril, who says that “I had a good relationship with trees when I was a child. There was a free world up in the branches. And the medium, wood, invokes environment and figures within the environment.” We should all be so lucky as to feel so connected to the world in which we live. Exploring Caril’s book, and being in touch via email, has reminded me of the slowness of trees, and encouraged similar slowness in a refreshing way.

“I proceed within a collaboration of the wood and the idea. Whether each blademark should be retained, I approach as an artist’s decision. Where I sand and smooth, I am trying to reveal the wood, within the shape of the idea” (pp. 26). In reading her book, I became fascinated with Caril’s practice. The text does some philosophical heavy-lifting (particularly in the section about halfway through called “Ideas and Stuff”): investigating ideas, ruminating on the interconnectedness of nature and people. The above sentence was one of the more specific descriptors of practice that stood out to me, but I still wondered about how final objects came into being, so I relished the opportunity to learn more. In speaking about her practice, Caril calls it a dance:

When I begin carving, I generally have a piece of wood I want to work on and an idea I want to work with. It often changes. Working in the wood is a dance of creation and discovery… I generally have a piece of wood going… it is spring here in the north, and as the snow on our property recedes, all that work reappears – stuff to be cleared, dug, tilled, planted, brush-cut, nailed, repaired, hauled off… With this, I am strongly motivated to have time for the carving that is gaining momentum under my hands.

Perhaps what best sums up both Chasens’s practice, and her book, is a brief but potent artist’s statement: “I value freedom, my fellow creatures, my world, and the creative process.” No matter the damn medium or subject, I find Chasens to consistently and effectively communicate this sentiment in her work. Though those of us in Philadelphia may not have quite so many trees to hang out with, we should consider our own unique relationships to nature. One local artist, Maddie Hewitt, does so in her own elemental work. Shifting from wood to water, Maddie says that “the relationship I have with nature has an influence on my physical, emotional and spiritual well being.” More on that next time…

Read part two, “Maddie Hewitt talks sustainable art making, and the reality of the climate crisis“