SYNESTHESIA describes the ability to sense and feel multiple senses as one– sounds become colors and colors become smells. With that, SYNESTHESIA is also a new series by Alex Smith, exploring the sounds, collaborations and imagery of the visionary artwork from culturally impactful Philadelphia albums. We’ll be exploring the ideas, story and vision behind iconic and soon-to-be iconic album covers from some of Philly’s best musicians and the artists they work with.

From the grounding intro sample “power to the people”, to the rousing Pet Sounds-esque swirl of album closer “Lissa Sleeps and Our Landlord Fixed the Heat”, beatmaker and hip hop producer John Morrison’s rising classic SWP: Southwest Psychedelphia is an album that is dynamic and layered, as soothing and familiar as it is impactful and propulsive. Released on Deadverse digitally and on cassette, the vivid imagery conjured in John’s music– largely trip-hop inspired hip hop beats stretched to beautiful perfection– is made even more stark by the inclusion of dreamlike collage work from just-as-soon to be classic non-binary black artist Dogon Krigga, a master colagiste and graphic designer residing in Columbia, SC.

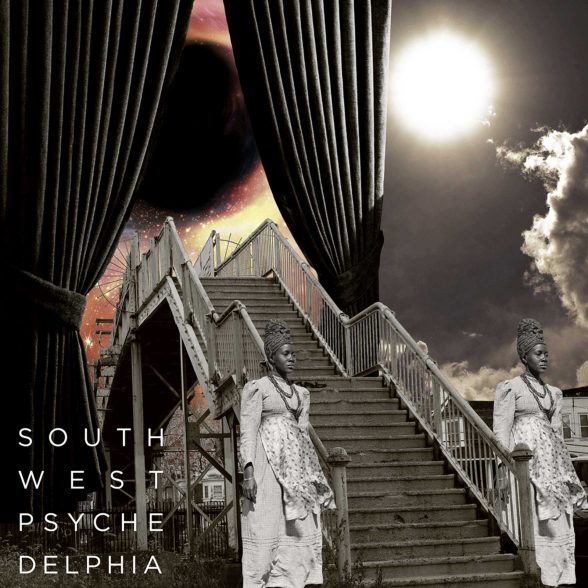

The cover is an orange and grey-scale handcut collage of two angelic, black figures in rustic, turn-of-the-century clothing standing in attention at an interstellar gate, the stairs to which are an infamously rickety bridge in West Philadelphia off Warrington, photographed by poet/artist/photographer Adrian Adonis. The sun sits high, radiating, but no light escapes– the scene is still dark and shadowy, except for behind a curtain, where an ethereal universe awaits. The juxtaposition of the hardened urban landscape with the shadowy and the stellar resonates with Morrison’s music, songs where the samples range from ominous news broadcasts about ATM robberies to interactions at the papi store where John himself seeks to procure a chicken cheese-steak. This marriage of the rudimentary with the otherworldly is a staple in Krigga’s work and was a key aspect in Morrison collaborating with them.

“I think that juxtaposition is common in Black art,” Morrison explained via email. “I don’t exactly know why but it’s like a thing that we see and have become adept at expressing, that connection between the worldly and the otherworldly, the urbane and the cosmic. Speaking for myself as a musician, composing pieces that accommodate both of those modes is like a way of honoring all of my influences.”

For Krigga, it is also an easy marriage of ideas that feels natural. In an email he wrote, “This juxtaposition is very intentional for me,” Krigga explains. “Niggas are in the greater cosmos. Niggas are of the greater cosmos. Often times the concepts of God (outside of Abrahamic systems), the future, astronomy, astrology, nature, etc., are whitewashed and seen as something that niggas from certain socio-economic backgrounds are either unconcerned with or gate-kept from. So I wanted to disrupt those spaces, groups, and communities with unapologetic images of Black-ass people fully immersed in the beauty of the cosmos.”

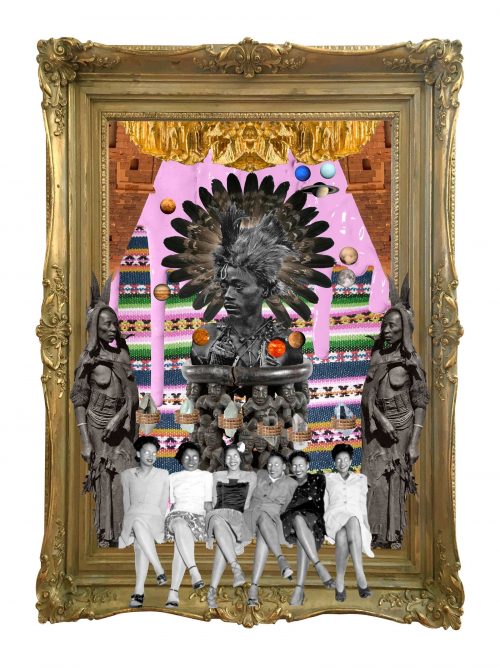

Indeed, in Dogon Krigga’s exhibits there exists an intemperate playfulness, where subjects resembling African kings and queens and warriors are adorned with gold chains or clutching microphones like hardened rappers, all back-dropped by the cosmos, spiraling planets and stars. In Ol Buttermilk Sky, two black fingers hold up the peace sign as sun-like orbs bounce around, snakes slither from a ghostly being in a red gown. The esoteric nature of the collage designs embody the strangeness of Dada, but the subject invokes the jagged, epiphanic revolutionary discord of Romare Bearden. This stylistic experimentation is not just a part of Krigga’s artistic journey, but their personal one as well:

Eventually I reached a point socially where I was around some really radical women and non-men who gave me the jewels to really unpack the toxic ideas I was raised with and still found in spiritual spaces. So my art, my politics, and my spirituality have reached an amorphous point where neither can be fully distinguished from the other. So now everything I create is naturally imbued with my social and spiritual principles and practices. This growth taught me to do my due diligence before appropriating symbols and objects from African cultures. It taught me how to honor Black bodies, especially femme bodies, in my art. It taught me how to elevate our form and refrain from the tacky, hypersexualized visual tropes that a lot of hotep-aligned artists lean on. It taught me to understand the Black body in a way that doesn’t assault it with unnecessarily gendered symbols and a binary approach. It taught me to appreciate fat bodies and to love my own. It taught me that our unapologetically Black aesthetics aren’t to be treated as a taboo, or sinful indulgence, but to be a default.

Despite being from South Carolina, it was kismet that brought Krigga to Philadelphia to participate in radical artist Rasheedah Phillip’s Afrofuturist Ball, an event that set the early stages for Philadelphia’s current immersion in Afrofuturism, cyberpunk, and queer and black culturally leaning sci-fi imagining. While Krigga displayed art, Morrison DJ’d and the two found mutual admiration for each other’s work. Morrison recounts: “I first saw Krigga’s work and met them at the Afrofuturist Affair Ball a few years back. I’ve found their work elegant and challenging and engaging, tapped in spiritually. To be honest, sometimes I feel like so much art from Black folks monetizes trauma for the gaze and approval of white folks, but Krigga’s work is Black as fuck in the way that it’s a visual dialogue for us by us.”

Krigga’s experience upon hearing Southwest was similar. “When I first heard the full album I was super excited because John sent me a couple joints to vibe to so I could catch the wave and create from that space. John creates an immersive world with his compositions, and that richness and depth provided me a really sturdy foundation to build the visual art on.”

It was the kind of empowering artistic collaboration Krigga had longed for. Despite finding a supportive network in Columbia, there have been setbacks, particularly with people not having a tonal grasp on the deeper concepts at play in their work. “For a long time I really considered the South to be a motherland of sorts for Black culture and people,” says Krigga on the difficulties of staying rooted in a community that seems to exhaust its ability to contain their artistic expression. “As problematic as that is, seeing as how we were kidnapped, sold, and brought to this land for chattel slavery, it doesn’t change the physics and metaphysics of the situation. This soil is saturated with the blood, sweat, and tears of my direct ancestors. My ancestors found a way to carve a little space out of this stolen land to love, connect with, consult with, and worship nature here.” While there is a clear connective conscience, Krigga laments: “I’m really considering my next move that will put me in front of an audience capable of digesting what I’m doing. I find myself constantly educating people here, and because of the time I’m always spending on preparing my audience with fundamental understandings of what I’m doing, it’s making me burn out. I’m ready to be in a place where the conversations about my art can go so much further because I’m not spending 20 minutes discussing “what is Afrofuturism? Have you ever heard of Octavia Butler? How about Sun Ra? Rammellzee perhaps? No? Oh…””

By contrast, Southwest Psychedelphia is an album deeply embedded in the fabric of its hometown. Created as a love-letter to west Philadelphia neighborhoods the album was made in and inspired by, the album embodies all the quirks, oddities, all the beauty and passion that the area emanates. Krigga’s artwork solidifies SWP: Southwest Psychedelphia as a work of collaborative magic, putting an elegant and visionary enchantment on a soon to be classic album.