Author’s Preface: I have known Dan for about 15 years. He took several art history classes with me as an undergraduate and graduate student at Towson University; as curator of the Holtzman MFA Gallery, I also worked closely with him on his 2007 MFA exhibition. He wrote his papers for me using his headpiece, typing out the words, one letter at a time. Dan’s impact on students demonstrates his perseverance and his leadership. There were several MFA students in a graduate seminar I was teaching, and Dan was one of them. The first night of class, everyone introduced themselves. Dan does not use an AAC (Augmentative and Alternative Communication) device, so you must listen very carefully to him speak. This is important as he believes that a voice translator removes his humanity.

Since I knew him as an undergraduate, I had become accustomed to listening to him, and I was able to help the class understand him when students had questions. Three students for whom English was a second language came up to me after class to talk. They said that they were thinking of dropping the course since it was so much reading and writing and discussion and oral presentations and it would be very difficult for them; but after meeting Dan, they decided to stay. The comment that has remained with me all these years is, “If he can do it, then we can too.” And they did stay with the course, and they all, including Dan, did very well.

When last year, a group of faculty and staff at Towson University decided to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act and the 20th anniversary of the Academy Award for best documentary for “King Gimp,” which tells the story of Dan Keplinger who was born with Cerebral Palsy and who is an artist, I volunteered to help with the project. Read about it here.

[Ed. Note: View short clips of Daniel speaking about his art. And for more about Daniel, and to purchase the video, “King Gimp,” see his website.]

One element of the celebration was to be an exhibition of his work — “Public/Private Conversations” — an exhibition I organized and led and which was to be in several empty stores at the Towson Town Center. This was a new experience for me and my staff. They were very nice spaces with white walls, but as we would design for a specific unit, it would be rented. And so, we would begin a new plan, working very closely with the highly supportive General Manager of the Center. In the end, due to Covid-19, we installed posters of the works at the Towson Town Center rather than the original works, which were in various locations and needed to be made ready for exhibition and would have required student gallery guards.

You can see a film that examines each work in the exhibition with Dan’s comments on what he was thinking about at the time that he made the images.

The idea of this show was to provide a broad overview of Dan’s career. Viewers can see more of his work here. It is powerful work, that like the King Gimp film, touches our hearts. Dan is an excellent artist. He is passionate about his subject matter and has developed a personal style that is highly recognizable. Though he has moved into the digital world, he maintains his expressive approach.

Below is an interview by the author with Dan Keplinger:

Susan Issacs: When did you know you wanted to be an artist?

Dan Keplinger: I always enjoyed art as a child and how I could express myself without talking. I wanted to pursue art as a profession in some capacity during my high school years. I even took my art portfolio to MICA (Maryland Institute of Art); they were very interested in having me as a student but at that time the campus was not that wheelchair friendly.

SI: Was there someone who inspired you to become an artist?

DK: I would not say there were people that inspired me to be an artist. It was more finding mentors who were willing to let me prove I could do the work. Being that I do have a disability, I ran into a lot of resistance to the idea of me taking art classes. So, after I started to work with Charlie Schwartz in high school, I spent a lot of time in his classroom over the next four years. The same thing happened with Professor Stuart Stein at Towson University. Once he saw how determined I was, I was able to complete my first class with him. He was willing to adapt courses so I could meet degree requirements. Decades later he helps as a mentor and advisor when it is time for the next stage in my career.

SI: Who are some of the artists whose works you have looked at, past or present, for inspiration?

DK: My life has always crossed paths with Chuck Close. My first few paintings were done with sponges instead of brushes. So, there was a comparison to Close, who also at that time must had been diagnosed with his disability. I even wrote a letter to him, and one of my high school art teachers knew a professor who taught a member of his family. I do not even know if he got that letter.

But maybe that was why I had a chance to meet him at my Phyllis Kind show in 2004. I do not think it was more than five minutes. I only remember shaking hands, putting our chairs side by side, picture, picture, picture and then we both were separated by throngs of people.

Recently, I was on zoom with a group of artists from Make Studio Baltimore and we brought up how you can even see some Close in my digital work, In that the work is still about my mark making.

SI: Did you find it intrusive to be followed around for the King Gimp film? It was done over a period of years. What was that like?

DK: Not really, when I did not want the camera around, I just did not tell them about what I was doing. Till this day the producers will find out about something I did, and they will be like. DAANN, why didn’t you tell us!!!!

SI: How has your life been changed from the film?

DK: Of course, it is cool being recognized all over the world, but even better is knowing that this changes people’s outlook on life. I once did a series of lectures for Service Coordination Inc. of Maryland and one day a staff member took me aside to speak with me. She started to explain how her secret identity was as an art appraiser and went on to say that she put me in the category of a Grandma Moses, not for our styles or backgrounds, but that a hundred years from now people would still be having conversations about me and my work.

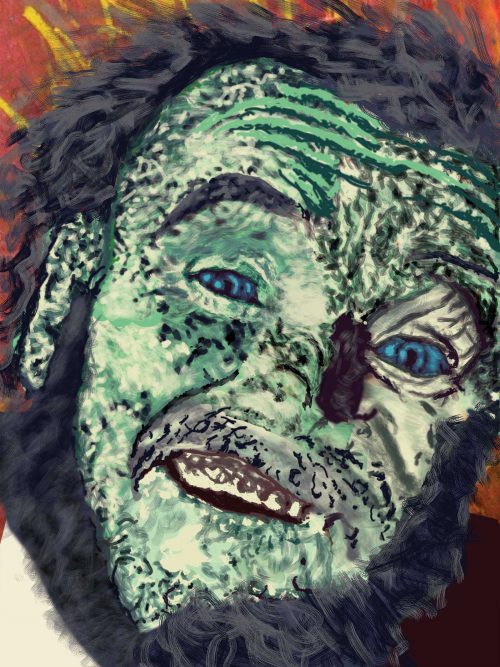

Digital Media. Courtesy Dan Keplinger.

SI: You are now working from home on the computer. How has that affected your images?

DK: When I first started to work digitally, my goal was to find a way to keep my mark making from disappearing since that is the most important component of my work. This is harder than one would imagine, because first I had to find the tools. Then I had to do a lot of trial and error with each setting then throw updates into the mix. I learned very quickly how to export my brushes and settings and to save the settings in my digital programs in order to reuse them again. Although, working with a computer as my medium is easier on my body, it does take longer and can be more frustrating when compared to working with traditional mediums. By creating my images digitally, I can add more detail by adding more layers. The work is still about capturing a moment in time and the emotions tell the story.

SI: I notice that your subjects have changed over the years. For quite a while you painted the people and objects in your world. Later you painted images related to travel and excursions. And still more recently, you are creating works digitally which are much more activist regarding people with disabilities. Can you comment on these developments in your work?

DK: To me, it seems to be a natural progression since my work is about the world I live in and the emotion I am experiencing at that time. Maybe I have become a people watcher because people have been watching me all my life. It could be my way of flipping a mirror and showing the true emotions they hide behind their expressions since most people just assume who I am as a person from seeing my disability first.

When I travel that brings me the most joy, but it can be frustrating as hell when places are not accessible. With having the ability to travel our country and around the world, I notice how far the disability movement has come though it is really in its infancy compared to other social movements.

Even before the current crisis of COVID-19 and Social Injustice, the disability community was facing danger in the present political climate. There are no government agencies to enforce ADA guidelines. It is up to me to file a complaint, take it to court and if I win, I am the one to go check that the business owner followed through. The bigger threat was when Congress wanted to make cuts to Medicaid. This would affect the ability of people with disabilities to live independently. Even more unknown to most people is that Medicaid provides funding for medical programs in Special Education classrooms.

I have been going out and protesting all my life. I have been fighting just to have my voice heard. I have been given a platform to make people think by expressing the emotions deep inside of me. Even if I reach just one person, I have done my job.

SI: Do you have anything you want to say to the art community at large about being an artist?

DK: Maybe New York is the LalaWood for artists as Hollywood is the LalaWood for actors. Maybe my gallery career would have been a bit longer if we did not have the 9/11 tragedy, the recession, and now, we are in in midst of another tragedy, COVID-19. In these times, the arts are seen by many as a luxury and become all but forgotten. This is when artists should be valued the most; we can capture history as it happens. We can provide people with an escape from reality, a haven. We also have the power to piss people off so much that they want to defund the arts, but most importantly, we have the power to spark conversations that can bring worlds together.

A collaborative project

Creating exhibitions is a collective process. In addition to thanking Dan for his professionalism and collaborative spirit, I must mention my close partner on this project, Michele Alexander, in the College of Fine Arts and Communication (COFAC) Dean’s office who has tirelessly worked to organize its various elements. I must also thank our Dean, Regina Carlow, and my colleagues, the TU Galleries Director Erin Lehman PhD, and the Department of Art + Design, Art History, Art Education Chair, Professor Jenee Mateer, for their support. My staff for the project includes our gallery tech, Michael Bouyoucas, and two of our MFA graduate students, You Wu and Kat Pfeiffer.

Many thanks to the College of Health Professions and COFAC faculty and staff, who coordinated and participated in virtual programming, particularly Professor and Clinical Associate Marlene Riley, who also first proposed the project. Thank you to Louise Miller for obtaining our TV donation and theatre student Michael Oduro for his voiceover work. My thanks to Filmmakers Susan Hannah Hadary and William A. Whitford for exposing this artist to the wider world. Lastly, I’d like to thank Emily Brophy, Sr. General Manager of the Towson Town Center, who has been extremely helpful with our many visits to the Center and whose hand of community partnership makes this exhibition possible.

Support for this project came from the Harold S. Kaplan Fund, TU College of Fine Arts and Communication, Additional funding was provided by BTU — Partnerships for Greater Baltimore, College of Health Professions, Office of Inclusion and Institutional Equity and the Office of the Provost, Weiss Markets, and TU Accessibility and Disability Services.

Public/Private Conversations is on view at Towson Town Center through October 20, 2020