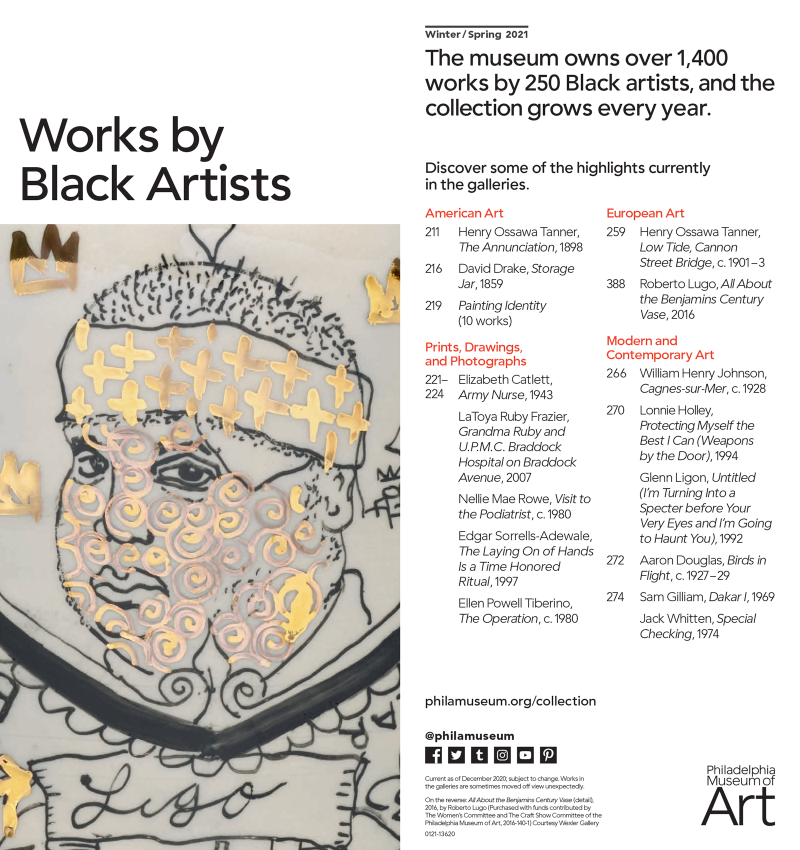

We may be restricted from most public activities but the museums are open again and I wasn’t the only one to rush to the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) for Martin Luther King Day. A hand-out in the lobby of “Works by Black Artists” was illustrated with a self-portrait detail from Roberto Lugo’s “All About the Benjamins Century Vase” (2016), so I started there – which meant going to the third floor, European galleries.

I passed underneath the altar screen and the room with Rubens’ eternally-suffering “Prometheus” (“Prometheus Bound,” 1611-16180), then past Judith Leyster’s young men ignoring the skeletal figure of Death as they binge on beer before Lent (“The Last Drop (The Gay Cavalier)” 1629), much like patrons of bars that have been crowded despite the Covid epidemic. Then, after a right turn, and passing the large Poussin deaccessioned by the Soviets so they could buy tractors (“The Birth of Venus,” 1635 or 36), a couple of galleries further I find Houdon’s marble bust of Benjamin Franklin (1779), in a rotunda; behind it in Gallery 388 is Lugo’s vase.

The mock-commemorative vase with its gilded sheep and ram’s heads is a terrific work, but gains nothing by its proximity to Houdon’s respectful portrait of the American statesman in Paris. Lugo’s Franklin wears a bandanna to hide his identity – masked for a hold-up presumably – which also reads differently when we are all masked. The “Benjamins” of the title is explained by the inscription around the artist’s self-portrait on the verso: “TO ALL THE KILLERS AND THE HUNDRED DOLLAR BILLS,” and the decorative patterning on that side of the vase derives from graffiti tagging. The work is not primarily about Franklin the man, but Franklin the image on our paper currency. Lugo questions what is chosen as the subject for commemoration and addresses contrasting economic possibilities, the choices that arise in response to social exclusion, and the decorative in vernacular versus high-art forms.

The ironic use of technique drawn from decorative arts and crafts as a medium of social criticism is exemplified by Lonnie Holley’s found-object sculpture ,“Protecting Myself the Best I Can (Weapons by the Door)” (1994), on the 2nd floor and two other works in the museum’s collection that are not on view but would be better company for the Lugo: Joyce Scott’s small but immensely powerful sculpture made of beads, “Rodney King’s Head Was Squashed Like a Watermelon” (1991), and Jayson Musson’s Coogi painting, “Trying to find our spot off in that light, light off in that spot” (2014). The works by Lugo, Scott, Musson and Holley make an interesting comparison to the gallery of work by Jasper Johns on the second floor. The sculptural pieces are on a similar scale. They all raise questions of what makes a suitable subject for tabletop sculpture and all provide unexpected answers. And Johns’ use of readily-recognizable imagery – numbers, beer cans, light bulbs, tools – finds a parallel in Musson’s re-deployed knit sweater, the decorative patterning on Lugo’s vase, and Holley’s improvised umbrella and cane stand: a piece of broken, ceramic piping holding a golf club, the “weapon”of the title.

On the second floor Modern and Contemporary Art galleries the works by Black artists made more sense. Gallery 274, the long space surmounted by Sol LeWitt’s work on the barrel-vault, contains a range of artists who experimented with painting conventions during the 1960s-70s, among them Alma Thomas, Jack Whitten and Sam Gilliam. Thomas’s “Hydrangeas Spring Song” (1976) is filled with a considerably wider variety of repeated forms than she often used and plays with the changing relationships between cobalt-blue figures and white ground. The pictogram-like forms appear to be breaking loose from a tightly-ordered mass at left into a less stable arrangement on the right. It is easy to read the large (6.5′ by 4′) but entirely abstract painting as a controlled crowd escaping into freedom and individual movement.

Jack Whitten’s “Special Checking” (1974) is one of a group of paintings shown at a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1974. They were made from multiple layers of paint dragged across the paintings’ surface with a squeegee or another tool, a technique Gerhard Richter would begin to employ in 1980. Whitten produced figures within the striations of paint by placing strings beneath the canvas that were revealed through the rubbing process, a technique which Max Ernst called “frottage.” The dragged paintings were part of Whitten’s ongoing, dramatic experimentation with technique and yielded his later method of forming small, dried squares of paint to create tile-like designs across large canvases.

Sam Gilliam’s “Dakar I” (1969) is the most dramatic work in the gallery – a large, polychrome canvas gathered at the top and hung by a string. Gilliam’s un-stretched, draped canvases remind us that fabric, the support for most paintings, is also the stuff of clothing, curtains, tents and other artifacts that provide decoration as well as protection from the elements. He began to make the draped paintings in 1968 and they were among the most radical paintings of the period. In 1975 the PMA commissioned Gilliam’s “Seahorses,” a monumental installation of six draped canvases which hung on two external walls of the museum, visible from the Parkway.

Just off Gallery 274 is a small gallery (270) with work by Glenn Ligon, Lonnie Holley and Nick Cave. A number of other works by Black artists are on view elsewhere in the museum and listed in the hand-out. The PMA is full of rewards for a socially-distanced outing.

“Ghosts and Fragments,” Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gallery 270, Main Building, Through Fall 2021

“All About the Benjamins, Philadelphia Museum of Art,” Online Exhibition, Ongoing

“Expanded Painting in the 1960s and 1970s,” Philadelphia Museum of Art, Edna and Stanley Tuttleman Gallery 274, Main Building, Through Fall 2021