[ED. NOTE: This post by Andrea Kirsh is Part 2 of a 2 Part review of “Senga Nengudi: Topologies” — currently on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art until July 25, 2021. If you haven’t already, you can read Part 1 here.]

After graduate school Senga Nengudi became involved with a group of African American visual and performing artists in Los Angeles who were excluded by white art institutions. Calling themselves Studio Z, they shared working and exhibition spaces and collaborated on a variety of artworks and activities. Members of the group included Marin Hassinger, who would become a life-long collaborator of Nengudi’s, David Hammons, Houston Conwill, Franklin Parker and others. Their unconventional art rejected calls by the emerging Black Arts Movement to create work of explicit political utility and racial uplift — which meant figurative art with an emphasis on prints, posters and murals. This was a stance common to all artists of color who worked abstractly.

Nengudi was trained as a dancer as well as an artist, so was steeped in an aesthetic based on the body. After having a son in 1975 she began a series that incorporated her thoughts about women’s bodies as both malleable and generative, subject to personal understanding and social assumptions. She turned to a material she would make her own, and with which she is primarily associated: pantyhose – mostly used by herself and her friends, sometimes by others. Any woman who came to puberty before the mid 1960s would remember the switch from stockings to pantyhose, which offered freedom from garters; very short skirts of the period depended upon them. At least throughout the following twenty years women were still expected to wear hosiery as part of proper office dress and in warm climates they represented restriction as well as freedom. In the African American community, men as well as women used nylon hosiery in hair styling.

Nengudi’s choice to work with used pantyhose began as a move that acknowledged her circle of friendships and common experiences. She also came to see the used garments, which she sometimes combined with other second-hand materials, or tied in knots, or filled with sand – which often yielded organic-looking forms readable as breasts, and sometimes testicles – as a metaphor for the abuse of enslaved, African American women’s bodies as wet-nurses. For one piece she placed a number of these breast-like forms, caged and controlled, within what look like the discarded springs from a couch or automobile seat.

In most pieces Nengudi left the origin of her material visible, where it inevitably referred to the bodies of the women who had worn and discarded the hosiery. She layered the pantyhose and stretched them almost beyond recognition, creating works based on tension – which implies an ultimate release. She used pantyhose of multiple colors and made works entirely of knotted hosiery so that it resembled braided hair. She often created work where the crotch was central, inevitably referring to the women’s pudenda, to their sexual agency as well as to histories of sexual abuse.

She titled these works with the prefix “R.S.V.P.” (“répondez s’il vous plaît,” or “please reply”), acknowledging the importance of her audience and inviting their response.

Nengudi also activated the pantyhose works by staging performances for the camera in which a woman, often her colleague Marin Hassinger, or even two performers would interact with the stretched nylon, distorting it in multiple directions against various parts of the body; later these evolved as performances for gallery audiences, recorded as videos. She used manipulated pantyhose as costumes for performances staged with a group of her colleagues in Los Angeles and for later performances in collaboration with colleagues in New York, which explored aspects of ritual and African mythology, improvisation, free jazz and spoken word texts. They drew from Happenings, Fluxus performance, Gutai activities and avant-garde theater. Both photographs and performance videos are well-represented in the exhibition.

Nengudi is the unusual artist whose work develops into new directions with age – always a brave step to take. In the late 1980s she enlarged her works into installations, some of which fill an entire gallery. A few incorporate pantyhose among assorted scavenged objects, and most of them rest upon a base of sand from which their forms protrude. The sandy landscapes are often marked with lines of colored sand, which reference several non-Western, ritual traditions of sand painting, including those of Native Americans, Indians and Tibetans. They create dream-like spaces filled with shapes that no longer refer to the human form but imply a space created for human contemplation of larger spiritual forces.

The final work in the exhibition is an installation, “Warp Trance” (2007) which grew out of the artist’s residency at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia. She visited local textile mills and filmed the production of jacquard weaving, in which the pattern is produced by the complex interaction of warp and weft – the vertical and horizontal threads on a loom. Such patterned weaving was unwritten, traditional knowledge of hand weavers, transmitted person-to-person; when produced industrially, jacquard weaving uses punch cards to drive the required movements of the looms – a prototype of industrial uses of computers.

For “Warp Trance,” Nengudi employed discarded punch cards to create the screens upon which the video is projected and worked with composer Lawrence “Butch” Morris, who incorporated sounds from the weaving process to create a sound track. The pulsating visual and aural environment is set in a large, open space that encourages visitors to move in response, and perhaps think about the changing labor and machinery of textile production, which has an inevitable association in the U.S. with the labor of enslaved African Americans in the production of cotton.

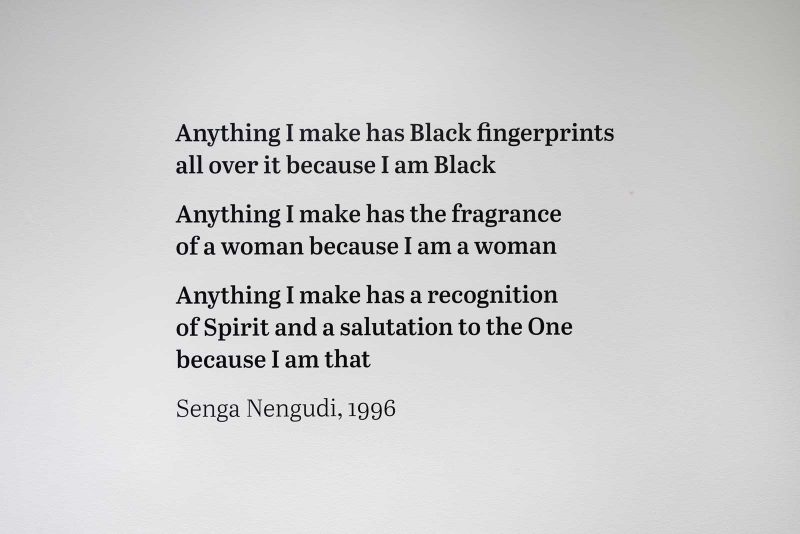

Like the pantyhose work, most of the installations are inherently transitory. The artist has explicitly stated her disinterest in creating permanent objects intended for sale and expected to be eternal. Her visual art is closely aligned with performance values, and with life, which is also transitory. Senga Nengudi’s art is inseparable from her life and her communal exploration of African and other non-Western sources of knowledge, mythology, ritual and art as an expansive resource for African-American and diasporic communities. Her work refers to both the individual and community, the joyous and the dangerous, history and the present, and creates its own, distinctive poetry of materials for provocative art that never tells its audience what to think.

“Senga Nengudi: Topologies,” Philadelphia Museum of Art, through July 25, 2021. Timed tickets required.