Holding on to the Past while Ruining the Present: From Rum Row to Grand Central to City House Charles

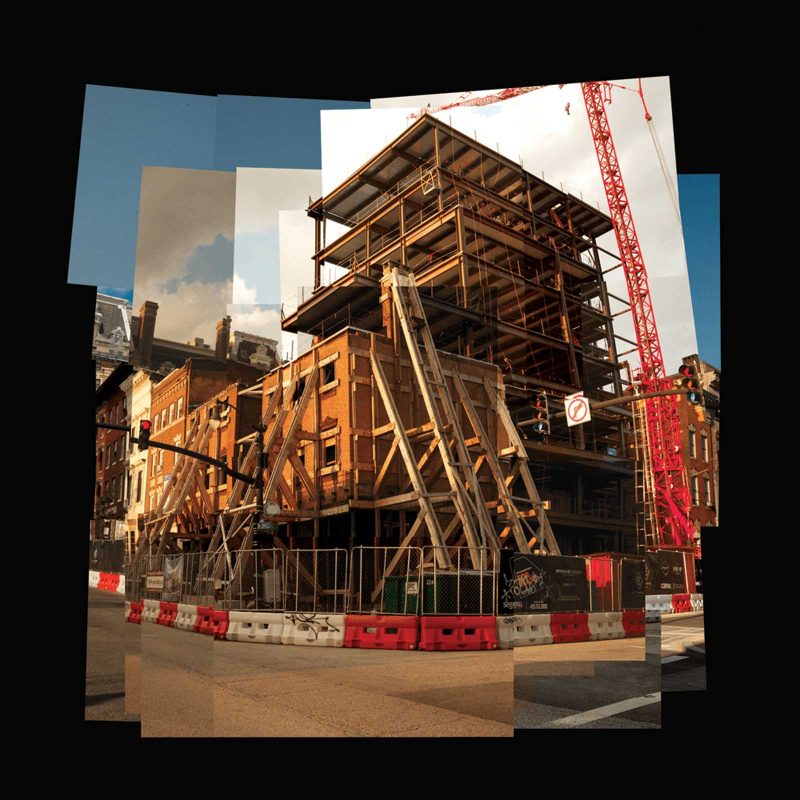

The building I will always remember as Grand Central, one of Baltimore’s most beloved LGBTQIA establishments– was demolished this past winter to make room for a newer, taller, more modern building –or, most of it was anyway. The property, a pair of 3-story red-brick rowhouses that stood at the northeast corner of Charles and Eager Streets since 1854– and dubbed “Rum Row” during a 1940s bout of post-Prohibition teetotalism, was torn down earlier this year; its second- and third-floor facades, however, have been preserved, held in place by an elaborate structure of angled wooden struts propping them up in the air. A mansard roof, added in the 1890s, was removed as well. Based on architectural renderings on a perimeter fence at the site, the mansard roof–or a facsimile of it–reappears in the final design of City House Charles, a 7-story, mixed-use office and retail building, scheduled to open next spring. Until then, the building continues to develop from within, growing up and out of the corset-like strip of brick and mortar of the ancient, antebellum walls.

In an earlier post for Artblog, I drew connections between our bodies and the buildings we inhabit, especially in the context of the quarantine due to the coronavirus. Our clothing is an important and sometimes stylish layer between our skin and the walls within which we live and love, work and play. In The Look of Architecture (2001), Witold Rybczynski, the Martin and Margy Meyerson Professor Emeritus of Urbanism at the University of Pennsylvania, argues that architecture and fashion have long responded to each other throughout design history:

The connection between décor and dress can be even more intimate, for architecture sometimes directly mimics dress. The garlands in eighteenth-century buildings are sculpted or painted versions of the sashes and flowered ornaments worn by men and women. The ancient Greeks incorporated elements of dress in temple architecture. This is most apparent in colonnades, which [art historian] Vincent Scully has likened to hoplites massed in a phalanx. (22)

With the association of architecture and attire in mind, and considering the fact that the new building will rise twice as tall as its predecessor, the marriage of past and present at City House Charles is like a sleek, elegant suit worn by a tall, modern person with a vintage sash wrapped around their waist. Will this clash of then and now stand the test of time? Further, when the ratio of old and new is so off kilter, why even retain the past at all? Why hold on to these bits of history?

The demolition of the old building took no time at all. Still standing in late 2020, the bulk of Grand Central was gone a mere few weeks into the new year. All that remained of its original life were these few fragile walls precariously held together like a house of cards reinforced with toothpicks. The original building lacked a basement, so the next phase of the project involved several weeks of digging down into the earth to create a subterranean level. During the process known as “shoring,” land under the foundation of an adjacent building– 4 East Eager Street– shifted, causing a portion of that building to sink a few inches. 4 East Eager was an apartment building, and thus had to be evacuated of tenants. As development of the new tower continues next door unabated, 4 East Eager still stands empty, a sort of architectural collateral damage. A thin crack runs up its facade. An even larger one runs across its white marble stoop, as if declaring: “Do not enter here!” Landmark Partners, the developers of City House Charles, neglected to inform the city about the damage until several months later, which has caused a local controversy.

Interestingly, I first learned of the damaged building several months ago, while speaking with a project manager on a smoke break on the sidewalk opposite the site on Eager. He openly lamented the fact that extant ceiling murals at 4 East Eager had been cut up by the addition of new walls to make modern apartment units. This historic building, in his view, was already destroyed long before the crack appeared. He added that Landmark Partners own all but the last building right before the alley on the other side of Eager Street from where we stood. Indeed, 6 East Eager, two doors down–which the project manager deemed the best building on the block–is now the headquarters to the City House Charles project, with those very words emblazoned across the main window. The project manager went on, informing me that 4 East Eager will most likely be razed, and that the empty lot might become an outside eating area for one of the restaurants that will open inside City House Charles. That conversation was several months ago. Since then, it’s become clear that not only will 4 East Eager Street be demolished, they won’t even be able to save its façade. So, while fragments of the past are preserved at the new site–soon to be dwarfed by the tower–an entire historic building will be lost next door.

***

Buildings aren’t entities unto themselves; they interact with the communities in which they’re built. A building can make or break a neighborhood or, at the very least, become an eyesore on an otherwise beautiful block. That is, it should not clash with the preexisting fabric of the city. When my partner and I first moved to the historic district six years ago, the site of the City House Charles project was Grand Central, an LGBTQIA landmark smack in the middle of Mt. Vernon, which our landlord at the time lovingly referred to as the “gayborhood.” As allies, my partner and I loved frequenting Grand Central. Its outdoor drinking area on the sidewalk along Eager was the perfect spot to sip a cocktail and have a smoke while watching the sun slowly set on late summer evenings. Projects like City House Charles, however, are altering the character of Mt. Vernon. Several gay establishemts were closing even as we moved in–the Hippo, a former gay nightclub kitty-corner to Grand Central, is now a CVS; and others, such as the Mt. Vernon Stable & Saloon, one of our favorite places to go out for dinner, closed during the pandemic never to reopen; and so on.

Mt. Vernon is also the site of where local filmmaker John Waters infamously directed his favorite actor and diva drag queen Divine to eat a dog turd at the end of his queer classic Pink Flamingos. A few years ago, the street artist Gaia painted a three-story mural of Divine onto the side of a rowhome not too far from the City House Charles site. The image was taken from the album art for Divine’s 1984 disco single, “I’m So Beautiful,” wherein the diva stares out at the viewer with those same words scrawled overhead. While the owners of the building approved it, the City’s Commission for Historical and Architectural Preservation was not initially informed and a hearing was held to see if the mural could remain despite its already being finished. Mr. Waters, who could not attend the hearing, was represented by an assistant with a letter that defended the mural depicting the auteur’s late friend. In the end, the commission approved the mural retroactively. It’s small victories like these that might save Mt. Vernon. City House Charles is another story.

***

I fear that projects like City House Charles represent a new trend in architecture, wherein the facade of the past may be retained, while modernity incubates within and gentrification extends without. It remains unclear whether or not City House Charles will improve the overall character of Mt. Vernon. Chances are rents will go up as the district continues to modernize and gentrify. As people get priced out of the neighborhood, the diversity of Mt. Vernon will almost certainly dwindle. Until it opens next spring, the jury’s still out on how City House Charles will operate as an actual building; in terms of its immediate impact on the district… Well, the damage is already done.