In Every Shut Eye Ain’t Sleep, Jennifer Packer’s tenderly portrayed figures and impressionistic flowers fill the varied sized canvases and flow in deep, provocative harmony along the white walls of the MOCA Contemporary Gallery in Los Angeles, California. These poignant works exploring human facets of memories are spaced light years apart and for good reason. It allows the viewer to become wholly suspended in these saturated atmospheres, to find themselves immersed in not just the subjects, but these surprisingly bold colors only an artist passionate about the act of painting could make.

In the first room of thirteen paintings, the large, majestic “Idle Hands” lords over the rest. A serene Black man, lying his head against an ambiguously depicted dog, prominent dark eye casually staring back, full mouth ready to smile. The color palette is minimal— reddish brown tones, moderate whites, pieces of powder blue, the brilliant yellow pants breaking up the monotony. The most intriguing elements to behold are the implied movements of the figure’s elongated hands and bulbous feet. There are traces of an outlined hand hovering above what Packer has fully fleshed out. It is the mapping of presence, of being unable to be still in a world that historically wishes someone looking like him would.

The subtle buildup of unique color, sharp and soft shapes, and haunting textures in “Untitled” lure viewers in feet first, with and without socks. Wearing a light red shirt and striking lime green pants, an anonymous woman gazes out from beneath a haze of thick black curls that shadow her mysterious face. Her posture is relaxed, almost vulnerable against a situation of pillows and concealed furniture. Her long fingers perch at her cheek and at the top of her thigh. Yet those toes are beautifully defined— something that can be noted in most Packer portraits— sculptural feet and hands are rendered with a humble and generous nature, having a heavy weighted mass to them.

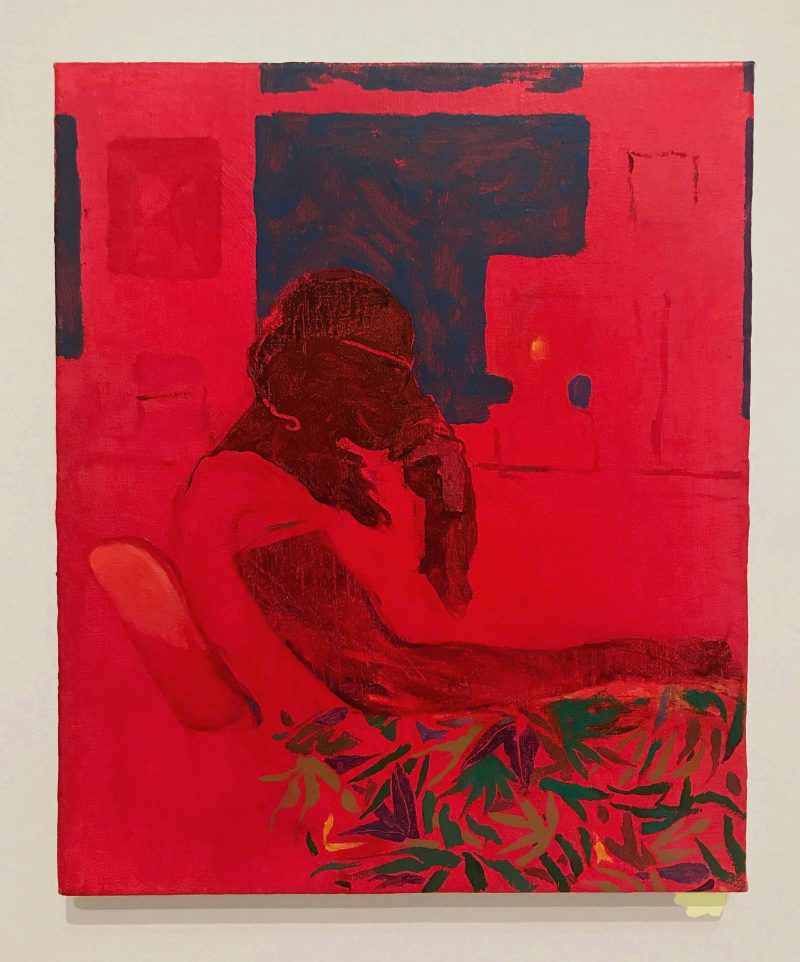

In “A Stone’s Throw,”— another intimately scaled painting—the profile of a figure is submerged in a vibrant red hue. Purposefully outlined from the background, she sits with a contemplative hand on her chin, wearing glasses, green and purple leaf pattern on her lengthy skirt. A blue paint glaze atop the red suggests a window. Other fine details such as the parting indicated in her hairstyle, the emotional positioning of her one eye, her outstretched arm, her slight reclining in the ghost of a chair— all play pivotal roles that reminded me of a modern day ode to Henri Matisse’s “L’Atelier Rouge” aka “The Red Studio.”

“Laquan (I)” and “Laquan (II)” are two large floral paintings beyond simple still life reproduction- Packer describes them as funerary bouquets. “Laquan (I)” has a fiery palette— an overall warm orange with vertical yellow lines and pink roses both blooming and budding in the foreground, perhaps a metaphor for rebirth and growth. “Laquan (II)” is an encompassing V repeated in the center and the manner of the leaves— all in greens and browns emerging from a somber yellow background. These two specific flower paintings are the only two titled with a person’s name, awakening Claudia Rankine’s poetic line—“sensations form a someone”:

“You like to think memory goes far back though remembering was never recommended. Forget all that, the world says. The world’s had a lot of practice. No one should adhere to the facts that contribute to the narrative, the facts that create lives. To your mind, feelings are what create a person, something unwilling, something wild vandalizing whatever the skull holds. Those sensations form a someone. The headaches begin then. Don’t wear sunglasses in the house, the world says, though they soothe, soothe sight, soothe you.” — Claudia Rankine from “Citizen”

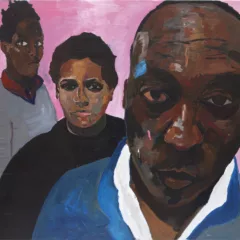

The second gallery features five paintings and seven framed charcoal drawings. However, six drawings along the wall— all “Untitled”— have a unifying theme: exhaustion, tiredness, rest. Two vertical drawings— a closeup of a profiled man with active hands placed on his agonized face and another man encased on furniture, sitting with the heels of his feet pressed together— and four horizontal drawings, which study sleeping bodies. Even in the stark black and white contrast, Packer’s style comes through these charcoals: attention to solid mass versus outline, playing with presence/absence, movement, and gesture.

Small paintings “Tremor of Intent” and “Interior” express extreme degrees of care and compassion. The powerful “Tremor of Intent” reveals a startling view of head and shoulders layered on red washes. The ear is especially wonderful— notable highlights bringing it forward. From far away, the line work on the jacket mirrors the leaves in the flower paintings. “Interior” has the most dynamic palette range, experimental colors operating next to one another. A woman in a lustrous peach dress, animal house slippers, and hair updo concentrates on the book in her hand. She is off center in a quirky, lived-in room filled with domesticity— air conditioner, guitar, chair, scissors, books, desk, curtains. Among the strategically arranged chaos, her pensive face is artfully chiseled— light hitting her nose, her lips.

In Every Shut Eye Ain’t Sleep Packer pays close attention to every line and shape of chosen sitters, using diverse browns to differentiate racial integrity, and quietly adds personification to plants. The inventive colors give credence to feelings, to emotional complexity. This exhibition is a gratifyingly defiant honor to memory.

“Every Shut Eye Ain’t Sleep” is on view until February 21, 2022 at The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles on Grand. An exhibition of Jennifer Packer’s work is currently on view in New York City – “Jennifer Packer: The Eye Is Not Satisfied With Seeing,” is on view until Apr 17, 2022 at the Whitney Museum of American Art.