When painter Mary Obering moved to New York in 1973, her work was exhibited at Artists Space in one of their “Artists Select Artists” exhibitions, as Carl Andre’s selection. She was included in the 1975 Whitney Biennial and showed in NYC galleries through the 1990s, but sadly, her work has escaped recent attention. Her exhibition, on two floors at Bortolami Gallery through Feb. 26, 2022, surveys thirty years’ work of a truly remarkable artist. Her career has been an extraordinary investigation of the possibilities of geometric abstract painting achieved through manipulation of materials and technique, and her work resembles no one else’s.

“Announcement” (1973), nine-foot square, oil on canvas, is a painting of enormous presence. It’s colored bands and blocks have an almost architectural weightiness. The nine, differently-colored forms are executed in matte paint that is subtle in its polychrome variety and surfaces. The most densely-painted is a vertical upright of human height that stands calmly within its surroundings, somewhat to the right of center. This is the only work on view that was made using conventional materials and techniques.

Three paintings in the gallery upstairs, also from the early 1970s, show the artist questioning everything about the way geometric abstraction could deal with the subject of space. All are constructed from multiple pieces of canvas painted in acrylic, which are tacked onto larger, stretched canvases at top, but hang freely. “The Chinese Place” (1975), over six feet tall, is a study in multiple shades of terracotta with contrasting forms in white and in black. Obering covered the large, geometric areas with an insistent painterliness; visible scumbles reveal the 3-inch brush she employed. The black area is matte and shows evidence of activity in contrasting thickness of paint – in some areas it is impasto’d and is thinned to a stain in others.

Space in “The Chinese Place” isn’t depicted through perspectival illusion or implied via color contrasts, as Joseph Albers did, despite a formal similarity to his work. Obering called attention to the painting’s actual three-dimensionality via the faint shadows cast by the edges of the four, hanging, layered canvases and the occasional touches of a second color where one canvas meets another. Both effects hint at something hidden behind what we can see. This is particularly true where the partially-occluded canvas creates a form which is interrupted by the canvas in front of it. The painting demands attention to its construction and has a great seductiveness and even mystery, which it only reveals over time.

During a period spent in Italy Obering was attracted to the luminosity and sense of space inherent in the gilt grounds of medieval paintings, by their association with the architecture where they resided, and the implication that the gold refers to something more transcendent than mere painting material. She began to work with egg tempera on small panels with contrasting areas of gilding. She developed an unprecedented technique of layering the tempera so that a color would inflect a differently-colored paint above – something associated with the glazes and scumbles of oil technique; it is an effect not thought possible with tempera. The paintings were still resolutely abstract, and as viewers moved in front of them they changed with the reflections from the gilded areas.

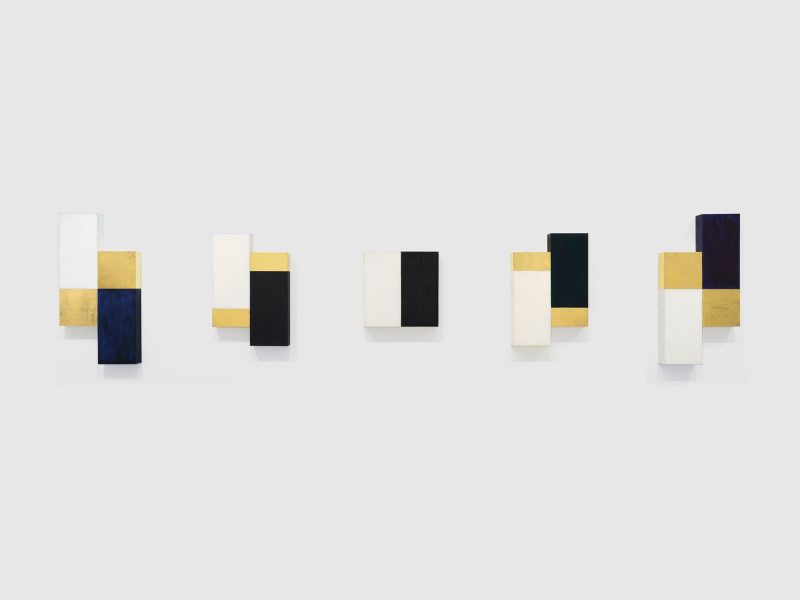

“Archangel” (1990) is the single, didactic work in the exhibition, revealing in discrete blocks the layering process of Obering’s technique: fiberboard panel, gesso ground, followed by graphite drawing followed by paint, and clay base for gilding followed by the application of small sheets of gold. By the 1990s the artist enlarged her working scale with multi-panel works, either adjacent panels or hung in series, and more interestingly still, she increased the depth of the panels and began to paint and gild their sides as well as their faces. She still worked with blocks of single color which contrasted both with other colored blocks and gilt blocks. But the painted sides of these works also set up interactions between the panels and the walls on which they hung; they cast reflections upwards from gilding on their top edges, and shadows below, from the panels’ depth. The space of Obering’s work had entered that of its viewers in a particularly subtle manner, and one impossible to capture with photography. It shares that characteristic with the work of Robert Irwin and Mary Course. With the series of of six, 10” x 12” x 2” panels of “Story” (1999) and the three 24” x 30” x 2” panels of “KCB, BKC, CBK” (2003) the reflections on the walls above the panels are from narrow areas of gilding at top, casting reflections that look like candle flames.

The masterpiece of the exhibition is “Sail On (for Hyde)” (1998), a multi-panel work which is both deceptively simple and deceptively complex. It centers on a 24” square panel, 4 3/4” deep, bisected vertically in black and white. It is flanked at each side by what appear to be two pairs of vertical forms. These paired forms climb up the wall, the ones at left hang slightly below the central square while those at right hang slightly above. From a distance the work appears to have a reductive palette of gold, white and black. Closer viewing reveals the dark areas to be dark blue, brown, darker brown and a very dark green – all of which were achieved with Obering’s characteristic painterliness and color layering. The paired forms at each side, composed of varying proportions of paint to gilding, appear to be gliding past each other vertically in a choreography of gilding and paint, rectangles and squares. This sense of a shifting presence is compounded by the golden reflections along the top of each panel and the shadows cast below.

“Sail On (for Hyde)” carries a surprising, spiritual charge – the result of its complex simplicity. The comfort of its familiar, regular shapes, the tension of its perfectly-calibrated proportions, the deceptive clarity of palette, the slow progress up the wall. Then there is the magic of that golden glow above each panel. Paintings don’t glow. Not in our era. The devotion this type of painting requires is time and attention. These are no more fashionable than the idea that art might reach us on levels beyond the rational. Mary Obering’s work offers rare rewards for agnostics and believers alike.

“Mary Obering: Works from 1972 – 2003” is on view through Feb. 26, 2022 at Bortolami Gallery, NYC.