Laurie Anderson describes herself as a storyteller, and she has created multi-sensory narratives on experimental music stages, at popular music venues and in museum galleries. Her work has largely been performative, yet rather than emphasizing documentation and relics of performances, The Weather, an exhibition spanning fifty years of her work, on view at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden through July 22, 2022, is an environment of compelling, multi-media installations which flow into one another, and more than a dozen works are new. The exhibition reflects her artistic imagination and thought as well as her technical skills and remarkable ability to deal with changing scale and translating formats. One has the sense of walking through the artist’s mind – both her conscious thoughts and her dreamscapes.

The Weather covers the range of the artist’s subjects, which center upon the construction of self, the instability of language and the changing pulse of the nation. From the position of a thoughtful individual, perplexed with much about contemporary culture and political life, Anderson invites her audience to ponder her musings within unfamiliar sensory realms and novel spaces. The artist has had a career trajectory unlike anyone else’s. She was trained in sculpture and moved from conceptual work addressed to small, art-world audiences in the 1970s to experimental performances that attracted widespread interest followed by unprecedented, international success in the popular music industry with “Oh, Superman” in 1982. This sophisticated presentation at the Hirshhorn will appeal to her fans and equally to anyone unfamiliar with her work.

“Chalkroom,” 2017. Projected video excerpted from virtual-reality piece (color; silent; 10:39 min.) Installation view from Laurie Anderson: The Weather at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, 2021. Photo by Ron Blunt

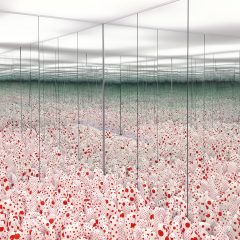

Anderson molds space with a sculptor’s sensibility allied to a musician’s understanding of the way space affects sound. In addition to speaking, writing, drawing, painting, singing and instrumental music she has added an evolving range of technical means to support her work, often using them in novel ways; the exhibition includes electronically-altered violins and voice, projected still and moving imagery, animatronics and virtual reality — adapted as projections here, to account for Covid restrictions. In one extraordinary gallery she has sited four sculptural pieces – including a talking raven and a shelf of objects that clatter with the vibrations from passing trains – within black walls and floor that she has entirely covered with text and imagery in multiple scales. It is compulsive, immersive and irresistible.

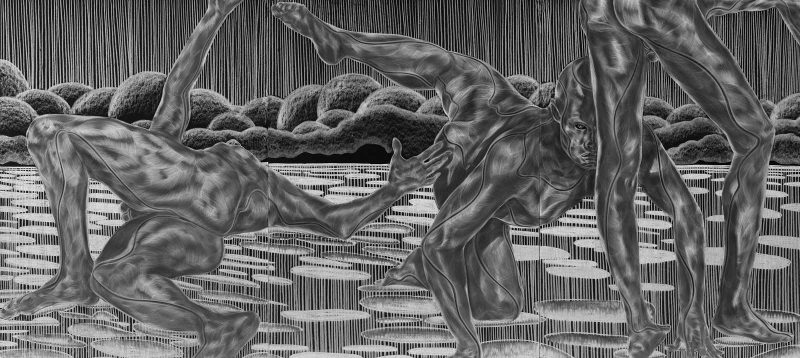

In contrast to Laurie Anderson’s varied technical tools used to expand her storytelling, Toyin Ojih Odutola has chosen the most basic of visual media: drawing. But the image that term brings to mind does not prepare you for her heroic, continuous narrative of life-size figures that inhabit the Hirshhorn’s inner, circular space. A Countervailing Theory (through April 3, 2022) with soundscape in three parts by Ghanaian-British conceptual sound artist Peter Adjaye, tells an Afro-Futurist parable of life in an unknown realm with forty drawings in white pastel and chalk on what appear to be blackboards but are actually framed panels on black backgrounds, hung on gray and black walls in a space darkened with black screening. The collaboration creates a spooky but plausible world peopled with characters whose lives and emotions are remarkably believable, even though unfamiliar.

There is an inherent drama to her massive, white drawings within a dark interior which sets up expectations much like entering a darkened theater, and that drama is rewarded with a mythical narrative set within the other-worldly, basalt rock-strewn landscape of Plateau State in central Nigeria. The story is filled with tension and danger, superbly executed and convincing in detail. The conceit of Ojih Odutola’s installation is that the drawings were enlarged from shale tablets that had been made by a previously-unknown, ancient civilization and were found during a recent, archaeological dig. Their culture was rigidly hieratic, run by Eshu warriors who created a subservient class, the Koba, who are entirely dependent and ruled by fear.

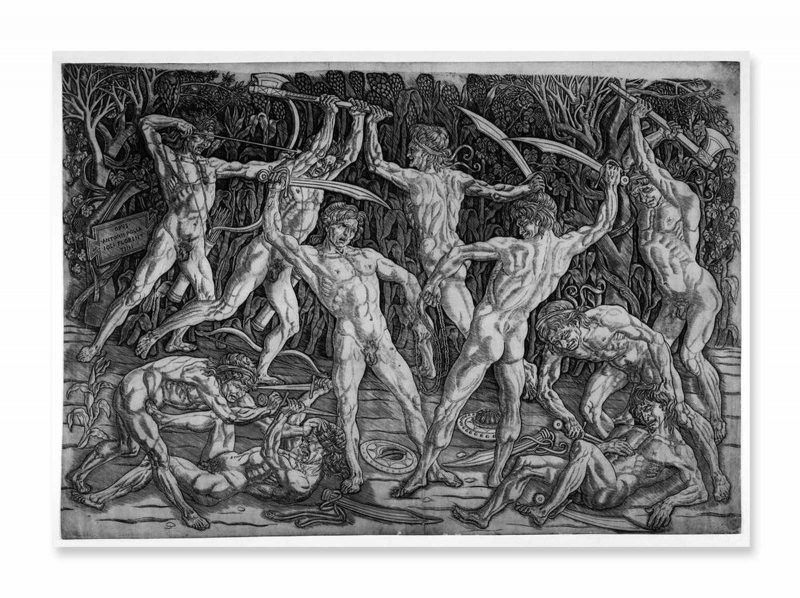

The story’s twist is that the Eshu rulers are all female and their slaves are male. It follows the early life and development of Akante of the Eshu and the Koba Aldo and their meeting and working relationship which turns into an illicit romance across class and gender lines. The story is supported by Ojih Odutola’s research, imagination and remarkable skills as a draftswoman. Some of the images are pure landscapes, others represent groups of figures with beautifully-choreographed movements, arrayed across the surface, much like Antonio Pollaiuolo’s “Battle of Ten Nudes.” Still others are closeups of faces, and Ojih Odutola moves among near and far views like an experienced film editor. Patterns of fine shading transform the figures’ skin into undulating landscapes. The bodies of the subservient Koba are marked – or branded — with meandering lines applied subcutaneously from head to toe. She contrasts the figures’ detailed shading with bolder and more geometric patterns which characterize the remarkable landscapes through which they move.

The atmosphere of A Countervailing Theory is heightened by Adjaye’s soundscape which includes ambient natural sounds of wind and birds with music performed on a variety of instruments – mostly West African drums, gongs, rattles, flute and thumb piano, with Western piano and strings and synthesized sound. The Hirshhorn provides a brochure with titles for each drawing, but it is well worth looking at the museum’s website before visiting the exhibition, for a much more complete narrative.

“Toyin Ojih Odutola: A Countervailing Theory,” through April 3, 2022. “Laurie Anderson: The Weather,” through July 31, 2022. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Check out the extensive virtual programming here!