I was drawn to Anne Ryan‘s work when I first saw two, small collages in MoMA’s collection galleries in the late 1960s. They made a big impression, all the more remarkable for works about the size of postcards. They haven’t hung with MoMA’s collection for decades; no responsible museum would keep works on paper on extended view these days. The current exhibition at Washburn Gallery to April 2, 2022, is the first time I’ve seen her work since my initial sighting. Ryan was a poet who turned to painting in middle age, then trained as a printmaker with Stanley William Hayter. When she was 60 she saw an exhibition of Kurt Schwitters’ collages that so impressed her that she immediately turned to collage, which she pursued the six remaining years of her life. Her collages were well-received. She had four solo exhibitions at Betty Parsons Gallery between 1951 and 1955.

Collage has become widely practiced, but was rare in the 1940s, its history associated with early Cubism and the Dada movement. And Ryan’s work couldn’t be more different from Schwitters’, whose collages almost always have indications of his materials’ sources. Schwitters assembled recognizable objects such as fragments of small hardware, wood off-cuts, newspaper, ticket stubs and other printed ephemera.Their fragmentary and forlorn condition suggests that he scavenged them from rubbish bins and the streets, and his handling of them often implies chance and disorder. The materials are very much part of Schwitters’ subject.

Ryan’s collages are controlled, her compositions stable. She worked with various types of paper and fabrics, some of which look like dressmaking remnants. Initially she included fragments of packaging and printed materials, which she eliminated in the later works; most have little emphasis on the history or sources of the materials, treating them rather like paint that she chose for its color and handling properties. The collages fall into two major types of composition. The first are postcard-sized, up to 7 by 5 inches, and their composition is established by their rectangular or oval format. They are entirely covered by variously sized, small, cut-out pieces — the largest being thumb-nail sized — which are arranged on axis and abut one another.

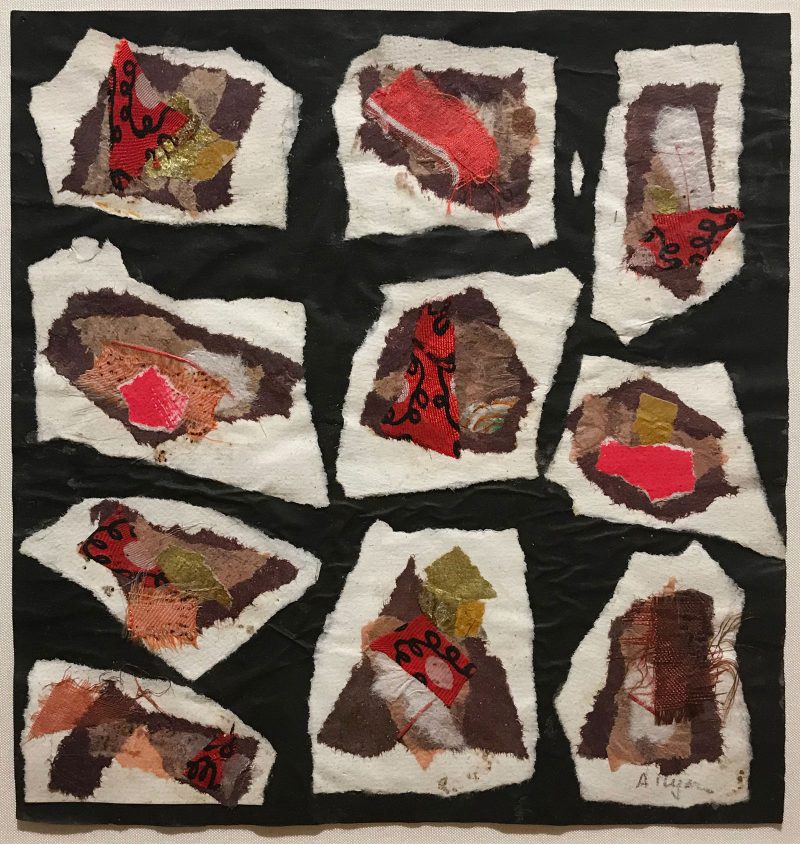

Most of the second type are slightly larger – up to 10 to 17 inches in their larger dimension. They have collaged elements in a range of sizes, often layered or overlapping, and the collaged paper has been torn rather than cut, hence irregular in form and fuzzy at the edges. The support is visible as part of their compositions and Ryan often used textured and/or colored, handmade papers for these supports. When she used textiles she emphasized their weave by unraveling the edges to reveal individual threads; these are the only small details within her collages. A small subset have repeated forms made of stacks of differently-colored paper which nestle within the rectangular format rather like hand-made chocolates in a box; the black paper of their supports creates a marvelous web of negative space.

Ryan’s shape-determined collages are the ones I first knew, and in their frontal arrangement of many small forms they bear some relation to Cubism, although all of Ryan’s work is resolutely abstract. They also have echoes of certain works by Paul Klee where he arranged squares of color with little or no ink drawing. Ryan created rhythmic distributions of color, and both her color choices and their arrangements within the compositions are the source of their seductive power. She had a finely-tuned sense of emphases and pauses, of positive and negative space, and could lead the eye throughout her finely mapped-out spaces. I can’t think of any artist whose most important work made so much out of so little; perhaps Ellsworth Kelly, but he had the advantage of a larger scale.

At a moment when her male colleagues in New York, Abstract Expressionists who also exhibited at Betty Parsons Gallery, were creating paintings of unprecedented size, Anne Ryan compressed her scale; her collages are smaller than her paintings and prints. Yet they are not miniatures. Their reduced size insists that they be viewed up close and by one person at a time. They emphasize the artist’s mental activity and visual sensibility rather than the physical activities expressed by large gestures and vigorous application of paint. Ryan’s collages do not lend themselves to post-war narratives of American freedom and prosperity.

I don’t know whether Ryan’s choice of materials and scale were intentional, or the expedient choices of a woman who had raised three children by herself and had to earn her own way. They are works which exceed their scale and history, ongoing affirmation of the possibility that abstract art can be intellectually challenging and emotionally moving, and that handwork can be manifest in many forms. If Anne Ryan’s collages don’t fit neatly within a movement and have fallen through the cracks of post-war American art history, it is our huge loss. They are important reminders for viewers and for today’s artists that first-rate art comes in many forms and needn’t follow the common path.

“Anne Ryan: Collages” on view through April 2, 2022, at Washburn Gallery, New York, NY