Professors have a way of digressing from their lectures. While a graduate student at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), I was mildly perplexed by a comment a philosophy professor made in class regarding Baltimore’s best public murals being found in the least affluent parts of the city. Was he criticizing this trend as something akin to the favela painting projects in Brazil where shanty towns are painted over with brightly colored murals, attracting and appeasing visitors, yet potentially fostering neocolonialism in the form of “slum tourism”? Whatever he may have meant, it was one of those offhand remarks that has stayed with me years later. Is it true? Are Baltimore’s best murals in its most impoverished neighborhoods? If so, why?

Let us first briefly discuss the art form. What exactly are murals? Who creates them and for whom? How long will they last? The modern word mural is derived from the Latin muralis, an extension of murus, or ‘wall.’ Of course, ceilings have served as the surface for murals as well. What would the Sistine Chapel be without its painted vaults? Michelangelo was working in the fresco mode of mural painting when he completed his masterpiece in 1512. Frescoes are a specific kind of mural involving the application of dry pigment to freshly laid (still wet) plaster. The two materials conjoin while drying, the paint becoming an integral part of the wall. Not all murals are frescoes. The majority found in Baltimore are of the wet-paint-applied-to-dry-walls variety. But murals don’t need to be executed in paint at all. A charming little mural near the corner of Calvert Street and North Avenue in the Station North Arts District of Baltimore was made in the ancient mode of the mosaic. Multiple fragments of ceramic, mirror shards, and other materials were configured here to offer a simple message of hope to anyone who happens past it.

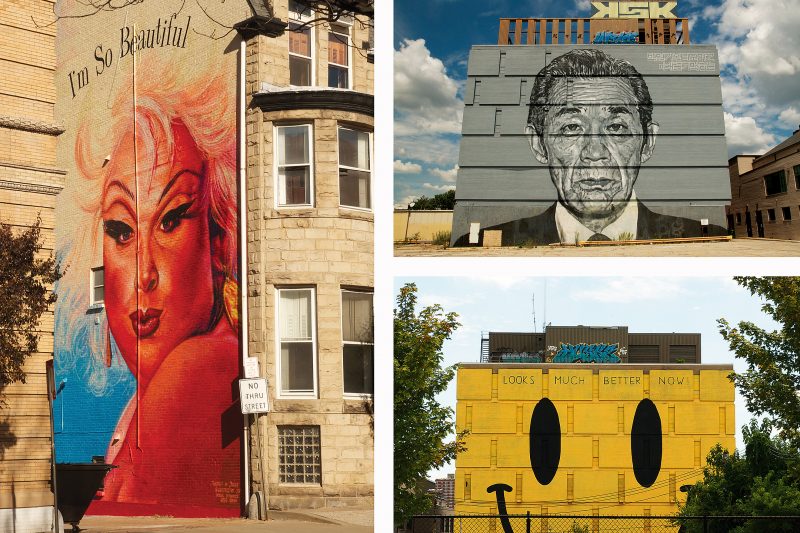

Considering the scope of this post, I will only focus on a few public murals found in Baltimore, most of which are on exterior walls and other surfaces. Some are produced by street artists, and may or may not be officially sanctioned; others are part of various community-based projects promoted by the city. Whatever their materials, merits, or purposes, public murals represent a unique, civic-minded visual artform that physically alters the urban topography while fostering a strong sense of place. The massive grayscale portrait of Mr. Kim, the first owner of the Seoul Rice Cake Shop, for example, quietly stares out over North Avenue from the wall of an otherwise nondescript building in Koreatown. Former MICA student Hendrik Beikirch (a.k.a.: ECB) painted the mural as part of “Open Walls Baltimore 2” in 2014. A phrase in Hangul (the Korean alphabet) appears in the top right corner, roughly meaning, “Wall opening Baltimore / Remembering the Future.” At six stories high, it’s said to be the largest portrait mural on the East Coast. This highly visible work of public art commemorates the life and work of a local businessman while celebrating the local community.

The mural of Mr. Kim, stoic and calm, captured in hues of gray, is a far cry – both in terms of palette and vibe – from the three-story portrait of Divine in the Mt. Vernon Historic District of Baltimore by the street artist Gaia, one of the most iconic and prolific of Baltimore muralists. Gaia’s bright, large-scale, Pop-like imagery and socio-political consciousness make him a favorite in the city. Born and raised in New York, Gaia moved to Charm City in 2007 to attend art school at MICA. After earning his BA, he chose to stay in Baltimore because, “I love the city in and of itself. I like its intimacy. I feel like a person here, whereas in New York it’s quite anonymous and there are many different communities that never intersect. It’s a wonderful feeling to be recognized on the street.”

Divine, the deceased actor, singer, and drag queen star of numerous John Waters films such as Pink Flamingos and Hairspray was once referred to by Baltimore’s favorite director as “the most beautiful woman in the world, almost.” For his monumental homage, Gaia was inspired by the cover art of Divine’s 1984 disco single, “I’m So Beautiful,” wherein the drag diva kisses out at the viewer with glamorous assertiveness, puckering her lips. As Gaia explained to the online publication Baltimore Fishbowl, the building owners specifically wanted a painting based off that photo from the album. Gaia agreed to paint the image provided they received approval from the estate that controls the rights to the image. “I like to paint very graphic images, very bold, saturated colors. This fit … my aesthetic,” he said. Gaia painted the song’s title over Divine’s head, as if transcribing his subject’s inner thoughts: “I’m So Beautiful.”

Several years since my former professor’s random observation about the location of Baltimore’s best murals, and after exploring large sections of the working-class locales of the city, I’ve concluded that his claim is not entirely accurate. Public murals can be found all over the city, regardless of socioeconomic conditions. All there has to be for great murals to exist is people. Baltimore has hundreds of public murals located in just about every one of its neighborhoods. In fact, there are so many murals in Charm City, it’s nearly impossible to track them all. Thankfully, Baltimoreans like Maria Wolfe and public initiatives such as the Baltimore Mural Program have done a great job documenting most of the many murals of Baltimore. There are similar initiatives in other cities, like Mural Arts Philadelphia. Due to their exposure to the elements, exterior murals are prone to fade and crack over time. However, muralists often touch up their work from time to time and there are efforts to preserve Baltimore’s most iconic murals. And new ones are being created all the time. In fact, I just learned of a new mural going up in the Waverly neighborhood of Baltimore commemorating Memorial Stadium (demolished in 2001–2002) where the Orioles used to play until they moved to their new home downtown at Camden Yards in 1992.

* * *

By integrating art into the public sphere, murals enhance the urban landscape. Indeed, along with monuments and statues, they represent some of the only non-commercial visual culture ordinary people see each day. Advertising, billboards, posters, and street signs compete for our attention in an increasingly mediated built environment. Public murals are a breath of fresh air in an otherwise disorienting sea of distractions. Galleries and museums are great, but localize visual art in a handful of locations, usually in the most elite areas of the city. Public murals directly engage with the communities in which they are found, providing a sense of place while allowing people to experience art. Wherever they are located, the best public murals reflect the hopes and dreams, histories and values of the surrounding communities, becoming integral features of the city, like paint in fresco walls. From the pictures of animals and abstract patterns of prehistoric cave art, to the political street art of the ever elusive Banksy, the urge to paint images on walls and directly engage with others persists as a distinctly human project.