Part 2

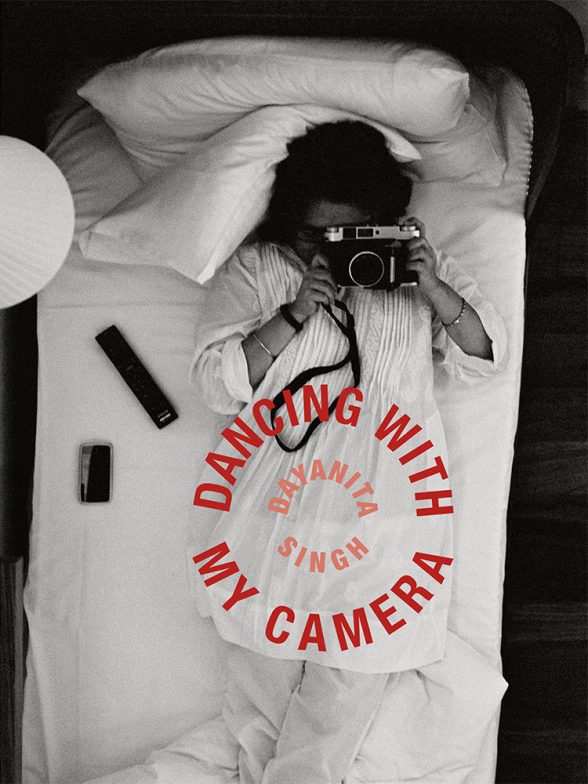

Stephanie Rosenthal, ed. “Dayanita Singh; Dancing with my camera”

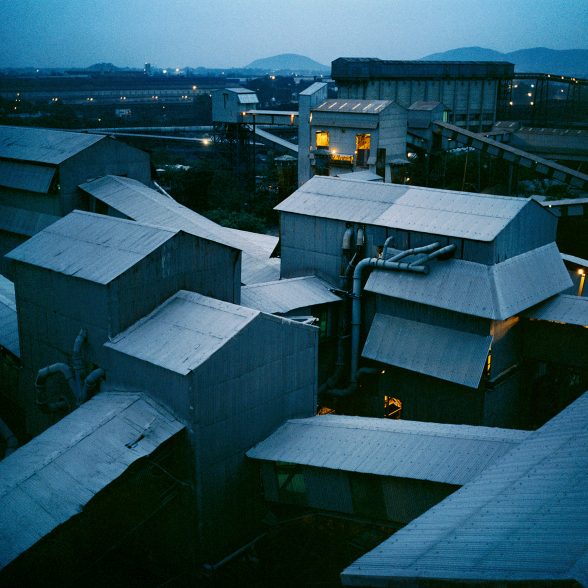

Dayanita Singh has an international reputation but has had limited exposure in the United States. Her work constitutes a major rethinking of photography’s physical formats and its circulation, so this small-format catalog to a broad survey exhibition is particularly welcome. The artist utilizes an archive of photographs taken over a forty-year period, many in her native India, as raw material. Her work explores the presentation and dissemination of photographic imagery; she questions all the assumptions of fine art photography, photographic books and museum exhibitions.

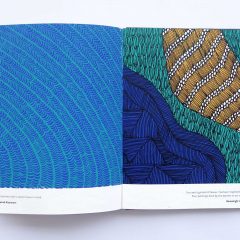

Singh is interested in photographs primarily as sequences rather than as individual images and has produced a series of printed books, a number of which she has termed “Museums.” She values relations through exchange which ground Indian social forms and spaces; to enact this, she built a book cart which she takes to art fairs as a way of directly distributing her books and meeting those who purchase them. Singh has produced “book objects”: wooden frames that hold printed books which can be slipped out of the frames as they are displayed on a wall. She has also designed three-dimensional wooden furniture to display series of photographs in museums, galleries and private collections; the curator or owner of the space determines the sequencing.

Contributions by Stephanie Rosenthal and eleven other authors address Singh’s work from a broad range of perspectives including her grounding in Indian classical music, theory of photography, the photographic archive she mines, experiments with forms of presentation, her suitcase museum as a portable institution, the use of montage, and her investigation of private and public space. Teju Cole describes his sequence of thoughts on encountering Singh’s work. The volume includes a chronology of the artist’s books, with illustrations of individual images, contact sheets, double-page spreads from published books, multiple museum installations and records of the artist with her work in varying contexts.

Stephanie Rosenthal, ed. “Dayanita Singh; Dancing with my camera” (Gropius Bau and Hatje Cantz Verlag GmbH, Berlin: 2022). ISBN 978-3-7757-5176-6. Art Book | Setana Books

Jo Rippon “The Art of Protest; A visual history of dissent and resistance”

Artists interested in working to advance political causes can always create posters, and “The Art of Protest; A visual history of dissent and resistance” offers a fascinating range of precedents from the early Twentieth Century to the present. The book was written in collaboration with Amnesty International, which emphasizes the importance of art to their campaign for human rights. Much of the artwork was done by illustrators, designers or design firms, some is only credited to the organizations that commissioned the posters, and a few are by artists of note, including John Heartfield, Kathe Kollwitz, Robert Rauschenberg and Anish Kapoor.

Jo Rippon’s text for each poster gives background on the cause it supported, the circumstances in which it was used and the visual rhetoric; for a few examples she even discusses the development of the image and reasoning behind it. Black Lives Matter’s logo was used for a poster without any illustration. Amnesty International’s poster in support of legal abortions was primarily text, punctuated by the clear silhouette of a coat hanger. The “Women Should” campaign by UN Women employed the visual style of advertising and Google’s typography to convey information based on an actual Google search: the crowd-sourced misogyny of auto-complete responses to the phrase “women should….” Some posters are purely image without text, and the visual style tracks that of other art over the course of a century.

The posters reveal some surprising imagery and interesting historical points. A 1989 Polish Solidarity poster used the image of Gary Cooper from “High Noon,” substituting a paper ballot for his gun; the designer expected the Hollywood cowboy image would evoke American democracy for a Polish audience. The U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare produced a poster in 1969 on behalf of clean air that takes its style from rock music album covers and posters. In 1966 the Lowndes County Freedom Organization chose a panther for a poster promoting voting because much of the audience was illiterate; Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale asked to use the image to represent the recently-formed Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. And it’s interesting to see how posters advocating women’s suffrage in 1913 in the UK, US and Germany have such differences in artistic style as well as text.

Jo Rippon “The Art of Protest; A visual history of dissent and resistance” (Palazzo Editions, Ltd and Charlesbridge, London and Watertown, MA: 2020). ISBN 978-1-62354-505-5. Penguin Random House | Barnes and Noble

Karen Moss with Lucia Fabio, eds, “By Alison Knowles; A Retrospective (1960-2022)”

Anyone interested in collaborative, intermedia, multi-sensory, computer assisted, performative or relational art as well as experimental poetry, printing, art books and art involving food will find this volume on Alison Knowles required reading. The surprise for many will be that the artist began these activities in the 1960s and continues to work, at the age of 89. She was the only woman in the original Fluxus group, and while she was not associated with feminist art activities or organizations, it is impossible not to read her practice as paralleling the development of second wave feminism. Her work must be included in art histories that have already, if belatedly, welcomed her colleagues Carolee Schneeman, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Yoko Ono, Senga Nengudi and Martha Rosler.

Knowles’ best-know work, “Proposition #2: Make a Salad” (or simply “Make a Salad”) was initially performed at the Institute of Contemporary Art, London in 1962 and several more times in the 1960s. Knowles reprised it in 2004 at the Baltimore Museum of Art, 2012 at the High Line, New York and 2019 for the Getty Research Institute, at the Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, among other venues. She has adjusted the framing so that what initially offered the surprise of a score performed with everyday kitchen tools rather than musical instruments has developed into a sound piece of rhythmic chopping by a coordinated group which is performed in contrast to conventional, classical music. The salad is always shared with the audience.

Food has appeared in other contexts throughout Knowles’ career. She ate the same lunch daily for two years as an extended performance, and has made varied use of beans as both material and subject; what is necessary sustenance for much of the low-income world is an ethical choice for a high-income population committed to sharing resources and reducing environmental damage. She has collaborated with colleagues from many disciplines, including John Cage, Dick Higgins, Ray Johnson, Marcel Duchamp and Rirkrit Tiranvanija — and always with her audience.

This catalog was sensitively designed by Content Object, Kimberly Varella to respond to the artist’s long experimentation with book formats. It employs multiple papers and varied dye-cut apertures in the heavy paper of section dividers, and the cover is a makeready produced during the printing of the interior pages, so that every copy has a unique cover. It includes essays by ten authors, a fully-illustrated chronology and a selected bibliography.

Karen Moss with Lucia Fabio, eds, “By Alison Knowles; A Retrospective (1960-2022)”. (University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive and Distributed Art Publishers Inc., Berkeley and New York: 2022). ISBN 978-0-9838813-4-6 Rizzoli | Art Book