The John J. Wilcox, Jr. Archives, at William Way LGBT Community Center, has been a staple for researchers, visitors, creatives, and curious individuals for many decades. The archives, run by John Anderies, are considered a public service, so visitors need not be doctoral candidates or published researchers in order to explore the archives. This focus on accessibility was, in part, the drive to renovate the archives’ space, making more room for guests and materials.

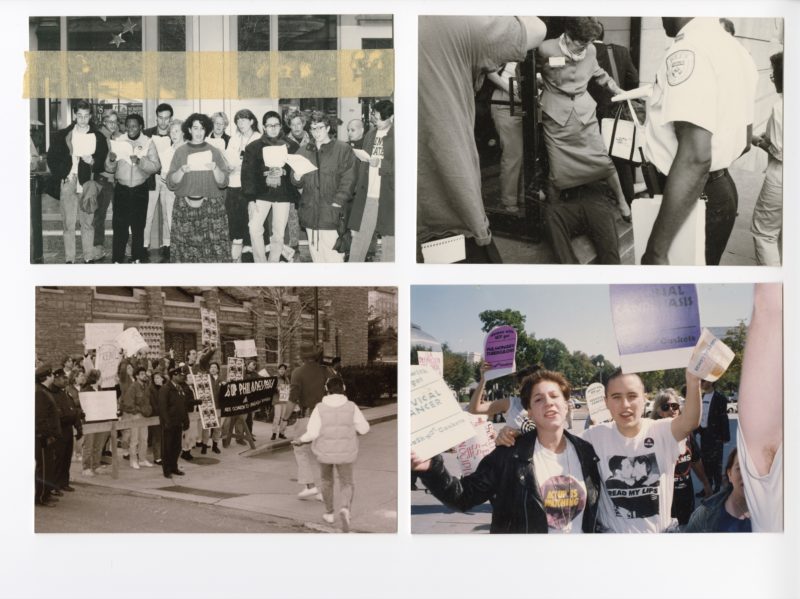

It was during this time of renovation, in 2019, that Rami George began their research into the archives. As a photographer with a particular interest in found imagery, Rami found that the William Way archives provided an exceptional range of imagery. Over three years of research have culminated into “Selections from the Archive: Rami George,” an exhibition on view at William Way now through February 23rd. The exhibition primarily consists of large format prints which feature a series of scanned images of the lives of LGBTQ people in Philadelphia in the late 20th century. The photographs are displayed with no commentary, allowing the viewer to free associate as people, protests, and parades flow across time. In addition to these prints, the exhibition contains bundles of protest signs wrapped in archival plastic, a few political posters, and a couple of videos; one that serves as a visual guide for the materials in the show, and one that contains the imagery of the scrapbook of Bill Way, for whom William Way is named.

I spoke with Rami George to learn more about the origins of “Selections from the Archives” and to hear them speak more about their personal practice and how it became intertwined with the rich LGBTQ history present in our city.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Logan Cryer: To start, could you introduce the project?

Rami George: The project is called “Selections from the Archives,” and it’s an exhibition at the William Way LGBT Center. The whole exhibition is work and content derived from the John J. Wilcox Archives at the Community Center. I had worked inside of those archives before, for my MFA thesis work. For that project, I was interested in these historical markers out in Philadelphia. I was using the archives to find more about the markers and find more about other people that I think should be marked.

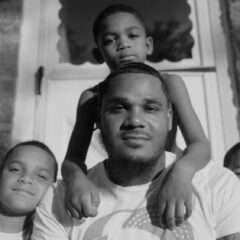

But I suppose that I just wanted to spend a lot of time in the archives, as much time as possible. And I wanted to see what came of it. My initial drive was that I wanted to look for less represented individuals and stories within the archives. The archives have a bounty, the biggest bounty is cis white gay history. And so, I was eager to find everything else: trans, non-binary, lesbian, POC, disabled, et cetera.

LC: They were renovating the archives around that time, correct?

RG: Yeah. They renovated and it’s been really lovely, way more space, less cramped, things are organized. Since it came back, I’ve just spent two to four days a week, many, many hours just in archives. In the beginning, it was just a whole bunch of looking and also cell phone documenting. The archives kept leading me to different places. Eventually, what came into the exhibition was both having to just be like, “Okay, I need to stop and see what I have so far.”

LC: Am I correct in understanding that there’s a particular part of the archive that you ended up delving into a lot?

RG: Yeah, yeah. There were many threads that were really interesting. There’s a work in the exhibition that is just all of my early searching and that’s a work on an iPad. I think about that as a visual finding aid. Archives make textual finding aids to be like, “This is what is in this collection.” For me, it doesn’t really work as a visual artist and thinker.

Another thing that came up that I wasn’t expecting were the Bill Way scrapbooks. William Way is named after this person, Bill Way, who was a white cis gay man who died from AIDS early on in the epidemic. I didn’t think that I was going to make a work about him, but his scrapbooks are in the archives and they go from his birth until his death. I spent an afternoon with them and it was incredibly moving and emotional. To understand the person through their own storytelling was really special. And then, to start to understand the history of the Center a lot more. So that also became something that was a big theme of the show, the Center itself. Also the last pages of the scrapbook… it’s just 32 blank pages and that was really emotional.

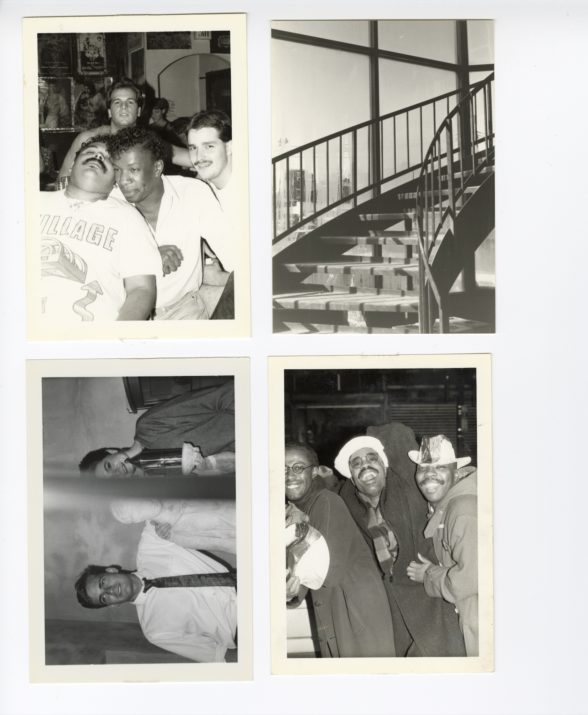

The other big project that came out of it was this LGBT publication called Au Courant. And it was active from 1982 to 2000. In my understanding, it was a smaller version of Philadelphia Gay News, which is still ongoing. And when Au Courant closed, all of their materials were donated to the archives. When I saw these boxes of the Au Courant photos, I was like, “Okay, that’s a big project because that’s a lot of images. And I want to look through all of them.”

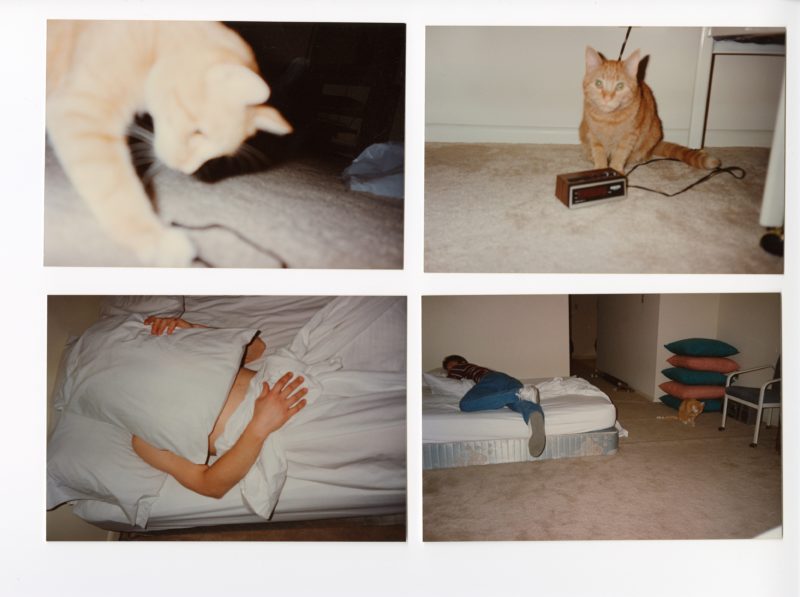

There’s these larger boxes that are unsorted and have more ephemera and some photos and, there are these boxes that are just the loose photos. That’s the material I went through. They’re not totally sorted yet. They’re in process. It’s very slippery and messy, which I really like. And there’s a rough chronology of time, but people reappear and time shifts. And in that, I was doing that same practice, which I was doing throughout the show, which I was looking for the less representative folks. It became that I also was just looking for images, photos that stood out to me. As an artist who mostly works with found material, a big part of my practice is collecting found images myself from thrift stores and my own family photos and other things. And then, I work with them in various ways. This collection was just like a treasure trove of thousands and thousands of images.

LC: What was your process for sorting through these images?

RG: I set some rules. I was like, “Okay, I have this big flatbed scanner, I can scan four images at a time.” Everything is roughly like the four by six image size. I have to keep the folders organized in their organization. In each box, they’re separated by little folders. I think the bundle that they were found in. I’d only go through each folder and I would decide what images stood out to me. I had the capacity to scan four at a time max, but sometimes only one image stood out or sometimes two, three, four or seven. And so, then I would be like, “Okay, I can scan four and three, or I can scan one.”

I really liked that, so there’s two forms of that project that I’ve included in the show. In the exhibition itself, there’s a selection of my selections that are printed on these, I think five by six foot photo paper. They’re organized chronologically in the order I found them. There’s line breaks on the prints for the boxes. So, similar to that iPad piece, I think about this also as a finding aid. If you’re like, “I need to find that image right there,” you could literally go and be like, “Okay, that’s box 26,” or I could tell you and it’s somewhere in box 26. I also want to encourage people to search on their own, so I’m not including exact folders.

The other part of that project was this audiovisual performance. When I was doing these scans, I would spend hours and hours the whole day just scanning photos. I would take them home and I would play with them and reorient them, see what made most sense. And I would often be up late at night listening to music in bed doing this. And there was something about the emotional space of images and music that I was super interested in, so I wanted to bring that to the exhibition. I wanted to invite a musician, a local person, a QTBIPOC, to do the score. I gave all the images to Savan DePaul. I was like, “I’m not yet sure on the timing or sequence, but I would love for you to respond in whatever way you want.” We had some meetings and Savan was like, “Okay, I really want to prioritize queer and trans music made during this time and also include some of my own work.” And I really loved what they had brought to it.

LC: You mentioned that in the past your practice has featured archival processes or archival research. Could you just talk a little bit more broadly about what your personal practice is?

RG: I moved to Philly in 2017 to start and finish my MFA at the University of Pennsylvania. I came for a variety of reasons, but a big drive was to work with Sharon Hayes, who is a faculty there and who shares a lot of interests in terms of queer history, archives, political work/poetic work. I came up through photography. My high school darkroom photo teacher changed my life, made me or led me to be who I am. There became a point where I was imitating vernacular photos. I was really into Wolfgang Tillmans, snapshots, everyday life, these sorts of things. And then, there came a moment where I was like, “Actually, there’s so much of this that already exists, so many of these photos.” So I became more interested in collecting and repurposing and reusing, remixing images and material.

There’s three tethers in my practice. One of them is queer history and archives. There’s work around my particular body in the world, which is child of an immigrant from Lebanon, thinking about a mixed race body, a diasporic body, but also one that doesn’t speak the language and that shared commonality between a lot of folks like children of immigrants or mixed race children of immigrants. And then, the last one is this ongoing research into this new age cult and community that my family was involved with in the ’90s. That one was a spiritual community and it splintered our family, but then we reconciled in this way and I’ve been interested in unpacking that.

LC: When did you start interacting with the William Way archives?

RG: I hadn’t yet really properly gone into an archive. When I approached John Anderies at William Way, I was like, “So there’s amazing photos in here. Could I scan them and use them?” And he’s like, “Absolutely.” He’s like, “Just don’t make my job harder. Tell people where the material is inside the archives in some capacity.” And I was like, “Okay, great.” And that’s just opened up all these doors. I discovered really important people in Philadelphia like Kiyoshi Kuromiya and Donna Mae Stemmer. Kiyoshi was a lifelong activist in the city. Donna Mae Stemmer was this local trans icon who had this practice of self-documenting all of her outfits in her home. And the archives had thousands and thousands of her photos, which are amazing.

LC: So do you see this project as a culmination of this work that you’ve done with William Way over the years? Or is this just one public iteration of research? Will there be others?

RG: There’s just so much material. I was like, “I could be in there for a million more hours than I probably will.” And so, “Selections from the Archives” feels like, again, opening up a really big project. Right now, I am trying to apply for funding to make a book. I am going to work with Mural Arts in the Summer to bring it out into a park, Louis Kahn Park, which is near Giovanni’s Room. We’re meeting with them to try and do some sort of programming collaborative. It’s also a cruising park. I’m into that shared history.

And so, I really think that the project is growing and growing. And I also really want to work with more elders. The Au Courant work feels like a portrait of Philadelphia, but also of New York. They also go to New York for every parade. So, I would love to take that to New York. I have ideas that it can be iterative.

I keep trying to get folks that were active in Philly from 1982 to 2000 into the show. I’m still exploring the avenues, but that’s something that I also really want to push at with the work. For the opening, there was a really special moment that someone recognized themselves in the photos. I was like, “Oh, that’s neat.”

LC: To close things out, when I was at the show and noticed that you have a long list of names of people to thank for making the project possible. Could you talk about the support that you’ve gotten for this project?

RG: I very luckily got an Art and Change Grant from the Leeway Foundation, which supports women, trans, non-binary artists. And they have a specific Art and Change Grant that is for projects that are social practice or collaborative or thinking through change in different capacities. I got $2,500 for that. Anytime I get money, I want to redistribute it to the underrepresented: QTBIPOC, women, trans, non-binary people.

I’m really into acknowledging and naming folks. I think it’s important. So, on the list of credits, there are people that helped me in studio visits. There are people that helped me in the production of the huge prints or things like that. Hannah Declercq helped me build the shelves, which are these beautiful floating shelves. I also wanted to name everyone that is involved in the public programming. So, quite a few people. For the closing reading, it is M.A.P. sa:de, Connie Yu, Arien Wilkerson, and Syd Zolf. So, those are five names that are included on the label. John (Anderies) is included. Alissa Roach, the curator in residence with the center, who is also an amazing resource and person. And then, I think I also credited John Cunningham, the elder who I interviewed. So, it’s just who helped me make this project, whether that’s physically, materially, conceptually, emotionally.