That SWARM lands comfortably in the heart of Philadelphia–an incubator for Black futurism and Afro-didactic, exploratory Black artists, is no miracle, but instead an expected drop-in, a city welcoming a kindred spirit. With SWARM though, the artist and filmmaker Terence Nance focuses his kaleidoscopic visions on creating space to explore Black and African diasporic love–particularly vis-à-vis intimate relationships. It’s work that aims to charm film buffs with its cinematic excursions (parts of Nance’s film An Over Simplification of Her Beauty appear here) and surreal enough to placate your local Afrofuturist.

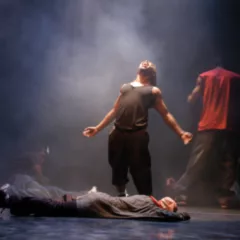

The five pieces on display at the Institute for Contemporary Art activate the senses with non-linear storytelling, a sense of the surreal, and deliberate pacing. Each work is delightfully enigmatic, yet gently restrained–the films don’t explode into chaos like the work of Michel Gondry, nor do they bury themselves in politic polemics and abstract cyber-horror tropes like Saul Williams and Anisia Uzeyman’s Neptune Frost. Nance’s vision of the surreal, especially for Black people, is his own, choosing to center his narrative on interpersonal relationships that explore the mysteries of the heart. Nance can get political, certainly—his HBO series Random Acts of Flyness explored the harsher realities of Black life–poverty, post-colonial existence, police brutality, erasure-with an “In Living Color/SNL on hallucinogens,” rapid-fire editing fervor. In SWARM it’s the piece Swimming in Your Skin Again that delves furthest into a political theme. Featuring his brother Nelson Mandela-Nance–a fantastic, abstract RnB and electronic musician–Swimming is a beautiful examination of worship, spirituality and nature, concepts that have been criminalized, re-appropriated, denied, and then re-contextualized in Black life since slavery. Filmed in the swampier parts of Florida, Swimming weaves moments of praise, of ritual contemplation, nature enhanced mischief-making and Nelson’s impassioned dancing and understated acting to create a transformative meditation.

But at the heart of SWARM is love–pained, fleeting, and out of our control. In another creator’s hands, these concepts would have unfortunate YA undertones, or worse, devolve into faux Noah Bambach-ian shouting matches between the two entwined protagonists. In that regard, the dangerously French new wave inspired Univitelin eschews the predictable narrative, taking the viewer in and out of time in a dizzying displacement of hyper-textual editing. The film plays on two loops placed opposite each other, sounds from each marrying the visuals of the other. Both films are viewed and heard from a rotating platform in the middle of the space. Experiencing this is like being physically transported in and out of various timelines; you experience the dark tragedy of two lovers as if you were living through it yourself, with chaotic rhythm and half-remembered snatches of time-worn moments, some replaying and others disappearing, lost to time.

Oversimplification, another work in which relationships are explored through animation and wildly edited docu-journals, is a documentary in some ways, a Gondry-esque splatter-shot cartoon in others, and a work that always surprises despite its mundane conceptual focus. I had trouble focusing while watching this piece, which is probably why I’ve never watched it in its entirety. As an excursion, as a part of SWARM, it’s perfect.

With all of its sheer beauty and dynamic film making, and as an important piece of Afro-surrealism, SWARM, though, seems to neglect queerness. This lack of broaching queer themes is something I’ve wondered about in recent art exhibits, albums, and films by abstract Black artists. The dearth of exploration in regards to gender and sexuality in works like Boots Riley’s fantastic film Sorry to Bother You, which examines seemingly every other topic under the left, political sun. Although such investigations are somewhat touched on, in the aforementioned Neptune Frost, or in music like that coming from seemingly pro-LGBT–or at least, not actively anti-LGBT–rap collectives like New York’s Backwoodz Studioz present an interesting dichotomy. These Black artists use surrealism, snatches of Dada, and the existential ontology of abstraction to describe the uncanny and the apocalyptic in Black life. That expression seems decidedly cis-heterosexual despite queer Black people living real lives that can often only be described as such and even more so. To be fair, there is a piece in SWARM where a person who could be read queer admonishes us from a park bench in a powerful, righteously angry screed against mediocrity–“steal yourself away from being industrialized, being industry, being the machine…making the mills. Don’t make anything!” the poet intones.

SWARM is Terence Nance’s brilliant, impassioned love-letter to the Black diaspora. It is moving, weird, and exploratory work that feels like the perfect dose of entropy in an already chaotic universe. SWARM is not incomplete, it’s a whole work–but ultimately it’s a fire mix-tape, an encapsulation of brilliance that, as Black life gets more overly legislated and thus more surreal, hints at even mightier works to come.