If you’re preoccupied, as I was, while looking for the entrance to the Judith Joy Ross retrospective at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, you might walk through the wrong doorway and instead find yourself looking at an installation of Japanese woodblock prints of Kabuki actors.

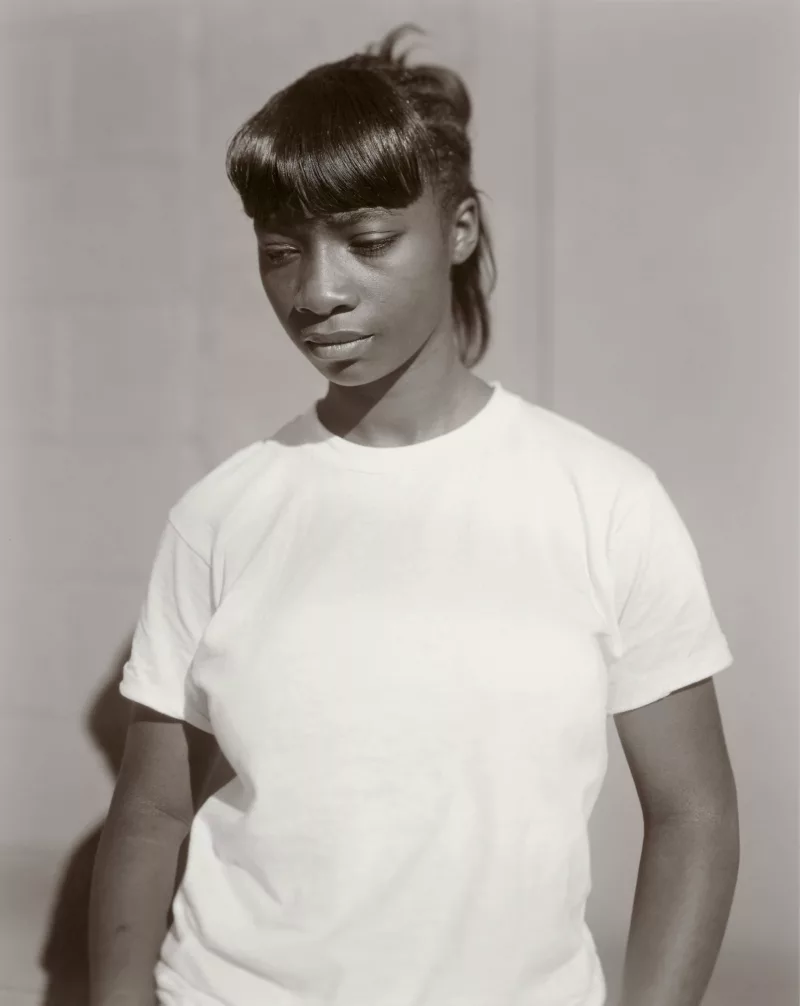

Like Ross’s photographs, the prints are mostly portraits. They intend to capture the idiosyncrasies of appearance and expression that can draw the fullness of a person from a sheet of paper. But while Ross’s subdued black-and-white photographs are marked by a “steely delicacy,” as the exhibit’s introductory text puts it, the colorful woodblock prints are highly expressive, brimming with anger, joy, and shock.

There are eyebrows raised at dramatic angles, mouths contorted into snarls, and eyelids drooping seductively—all the drama of a Kabuki play, rendered in two dimensions.

The prints are just as delicately crafted as Ross’s photographs, but they’re more fiery than steely: two equally sublime collections of images, two entirely different approaches to portraiture.

Walk through the right doorway, and the first thing you’ll see is one of Ross’s most well-known images blown up large enough to cover almost an entire wall. Two girls sit on a tall stump, gently intertwined. The girl on the left clasps her hands over her crossed legs and has a faraway gaze that is strikingly mature for her diminutive frame.

From a distance, the girl on the right appears to smile softly at the camera, but closer examination, made possible by the massive scale of the image—which is, in turn, made possible by Ross’s preference for a Deardorff 8-by-10 camera that produces large and extremely detailed negatives—reveals tensely pursed lips. No swords or snarls here; the high drama of her portraits is staged in glassy stares and awkward postures, not in the Kabuki theater.

The untitled photograph of the two girls, from 1982, is part of a series of portraits that Ross made in Eurana Park in Weatherly, PA, mere miles from Hazelton, where she grew up, the middle of three children born to parents of modest means.

She fell in love with photography in 1966 at Moore College of Art, long before she made her most famous photographs, like the portraits at Eurana Park. It wasn’t until she discovered the 8-by-10 camera in the early 80s that her style solidified.

For the first time, Ross was able to capture the minute details that define her portraits, which are on display as contact prints, meaning that they were reproduced from the original negative at exactly the same size, without any loss in resolution.

Ross, 76, still lives in Bethlehem, not far from where she was born. She has been able to find deep wells of inspiration both in her immediate surroundings and in far-flung locations. Since the Eurana Park portraits, she has made geographically specific series of portraits ranging from Philadelphia to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, to Paris.

The retrospective, on view until August 6, has arrived at its final destination after stops in Madrid, Paris, and the Netherlands. It begins with Ross’s Eurana Park portraits, which, according to the text on the wall, convey “what it is to be young and unguarded.”

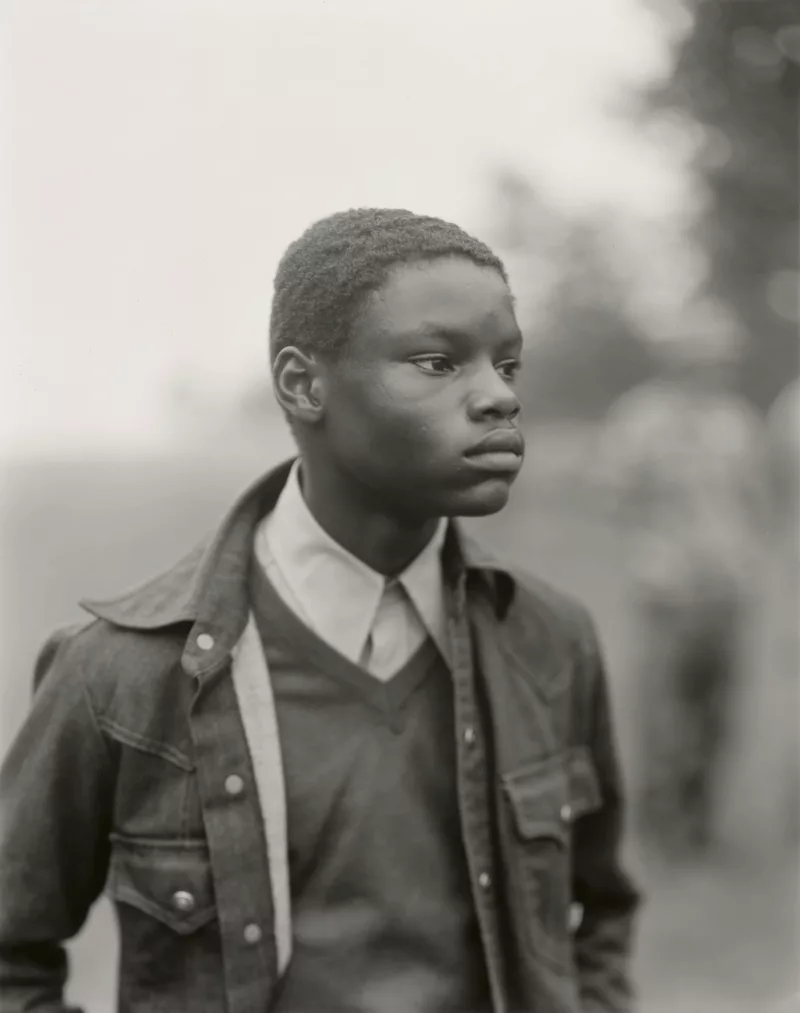

While the portraits certainly do capture the specificity of youth without being sentimental, very few of Ross’s Eurana Park subjects actually are unguarded, which is exactly what makes her photographs powerful. She finds the kind of depth and contradiction in her young subjects that are usually reserved for adults.

While looking at a touching but jarringly awkward portrait of a teenage boy holding a rake, one of my fellow museum-goers remarked, “I think he has a boner.”

Ross continued to explore the uneasiness of youth in a later series made at Hazelton High School. In one portrait, Ross photographs her subject in profile in order to capture the embarrassing softness of his sideburns.

Just beyond the Eurana Park portraits are a number of photographs by Eugène Atget (1857-1927), whose preferred subjects were Paris streets, not people. Ross, who has cited Atget as an inspiration, selected the photographs herself, which are paired with several of her own images that have no humans in the frame.

In “305 North Tenth Street, Allentown, Pennsylvania,” a breathtakingly beautiful scene observed through the narrow gap between two curtains, Ross manages to photograph a slender street tree as though it had an inner life. Atget’s influence is evident—his own photograph of a pair of curtains is on display nearby—but Ross is in no danger of looking derivative. By translating his ideas into her own visual language, she develops them.

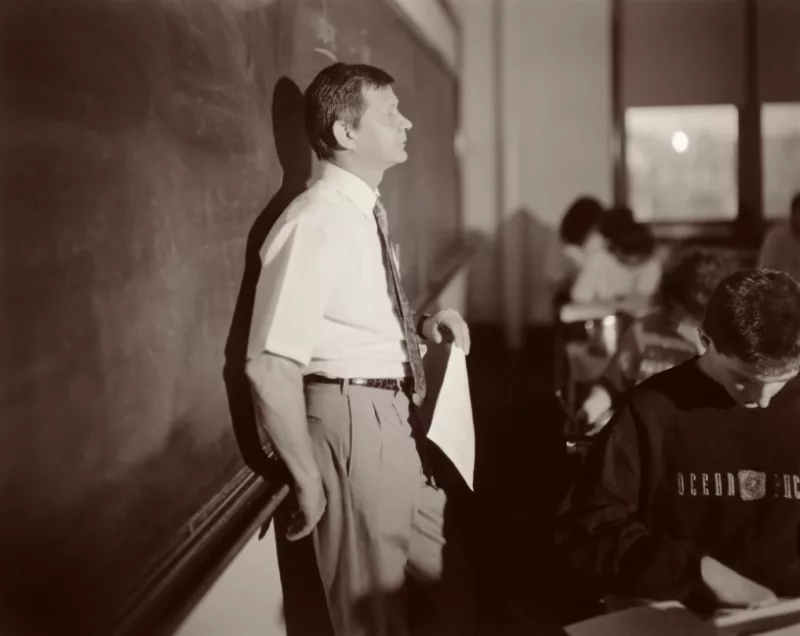

The exhibition, in addition to telling the story of her artistic growth, engages admirably with Ross’s politics. In 1983 and 1984, she shuttled between the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., and a Pathmark grocery store in Allentown, PA, situated next to a furniture rental business. She understood the people she photographed in these disparate locations to be connected.

“In Ross’s thinking,” one label reads, “[furniture rental] was an exploitative business model designed to take advantage of the poor, exemplifying a disregard for people that paralleled the treatment of soldiers sent to Vietnam.”

For her series Jobs, Ross photographed working-class people in Bethlehem, PA. The best-known image from the series is a portrait of a Citgo employee named Mike, whom Ross renders with quiet deference, as though he were carved from marble and standing on a pedestal.

At first, it is difficult to square these photographs with Ross’ portraits of members of Congress, which she made in 1986 and 1987 for a celebration of the bicentennial of the Constitution. She photographed representatives from both parties, including Strom Thurmond, a relentless opponent of civil rights legislation, and Robert Byrd, who began his political career by leading his local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan.

While Byrd, beady-eyed and reptilian, looks unmistakably evil in his portrait, Thurmond is small, wrinkled, and vulnerable—frighteningly sympathetic. But in both cases, Ross strips the senator sitting in front of her of all his pretension and authority. Her camera reveals the smallness of the supposedly important, just as it illuminates the greatness of the supposedly unimportant.

Ross’s later series—including Eyes Wide Open, a traveling exhibition about the devastation wrought by the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—“reconsider her nonpartisan approach to portraying those exercising their civic duties,” according to one label.

One of the best portraits from Eyes Wide Open shows a protestor named Annie Hasz at an anti-war rally. She stares firmly into the camera, and the ends of her hair look like the wings of the dove on the sign she’s holding. In less able hands, the downy innocence of the portrait would be too sentimental. As Ross composes it, though, it’s perfect.

The single sign of weakness comes at the end of the exhibit. After the printing-out paper she had used for decades was discontinued in 2007, Ross experimented with making color photographs. The results aren’t very good; color adds an uncomfortable extra variable to the precise balance of her portraits.

Still, the color photographs are an essential part of the retrospective. Ross has spent a lifetime mining faces for their complexities and contradictions. Her photographs are never simple, never straightforwardly evocative. Why iron out the creases in this portrait of her life as an artist?

At the beginning of the exhibit, by the Eurana Park photographs, I overheard a man telling someone else that he had grown up in Weatherly. I eavesdropped for a moment then introduced myself. His name was Ken Hensel, and he told me that he recognized a few of the kids in Ross’ portraits from around town.

“I know these people,” he said. He was 26 years old when Ross was lugging her camera around Eurana Park, much older than the kids in the portraits, but in such a small town their faces had become unavoidably familiar.

“Every kid spent their whole summer at Eurana Park,” he said.

One girl he remembered as a lifeguard, and one blond boy he remembered “because all the blond kids, their hair would turn green” in the water.

These faces had recently looked out from the walls of museums in Madrid, Paris, and the Hague. Tens of thousands of people have now looked into the eyes of the two girls sitting on a particularly tall stump in Eurana Park in 1982.

“Weatherly’s this tiny little town of two or three thousand people,” Hensel said. “To see this in Philadelphia, in the Art Museum…,” he trailed off, his voice wavering.

“It’s emotional.”

Judith Joy Ross, through Aug. 6, 2023, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. See more images at the PMA website.