The group show Songs for Ritual and Remembrance aims to display memories and histories of marginalized peoples, memorializing the unmemorialized, through the work of four very different artists.

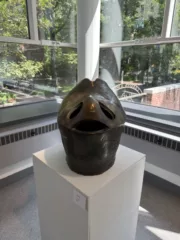

The show opens with a generous view of “Production 5,” a large richly textured paper piece by Adebunmi Gbadebo. Gorgeous blues and blacks come together in rice paper to weave a story of ancestry. The genetic link of hair works with the material connection of rice and indigo to create a multi-generational connection. Both rice and indigo were grown by her ancestors who were enslaved on the True Blue Plantation in South Carolina. This same blue carries through to the back of the gallery, highlighting a ceramic piece by Gbadebo, “In Memory of K Smalls died 19?? HFS”. A piece made from soil that her ancestors worked and tilled, with South Carolina gold rice placed in decoration protruding from the surface. Of the work, Gbadebo says, “The making of the work has been a practice of healing and a practice of care for their memories and what remains of their physical bodies, it’s in the soil.” An element of the installation is an audio track playing a hymn sung by the artist’s family at a funeral. The lyrics are “Sit down servant, rest a little while…I know you are tired, sit down and rest a little while”. Paired with the piece, “Pews”, two church pews built by her ancestors in 1890 a beautiful portrait of death and healing across generations is produced.

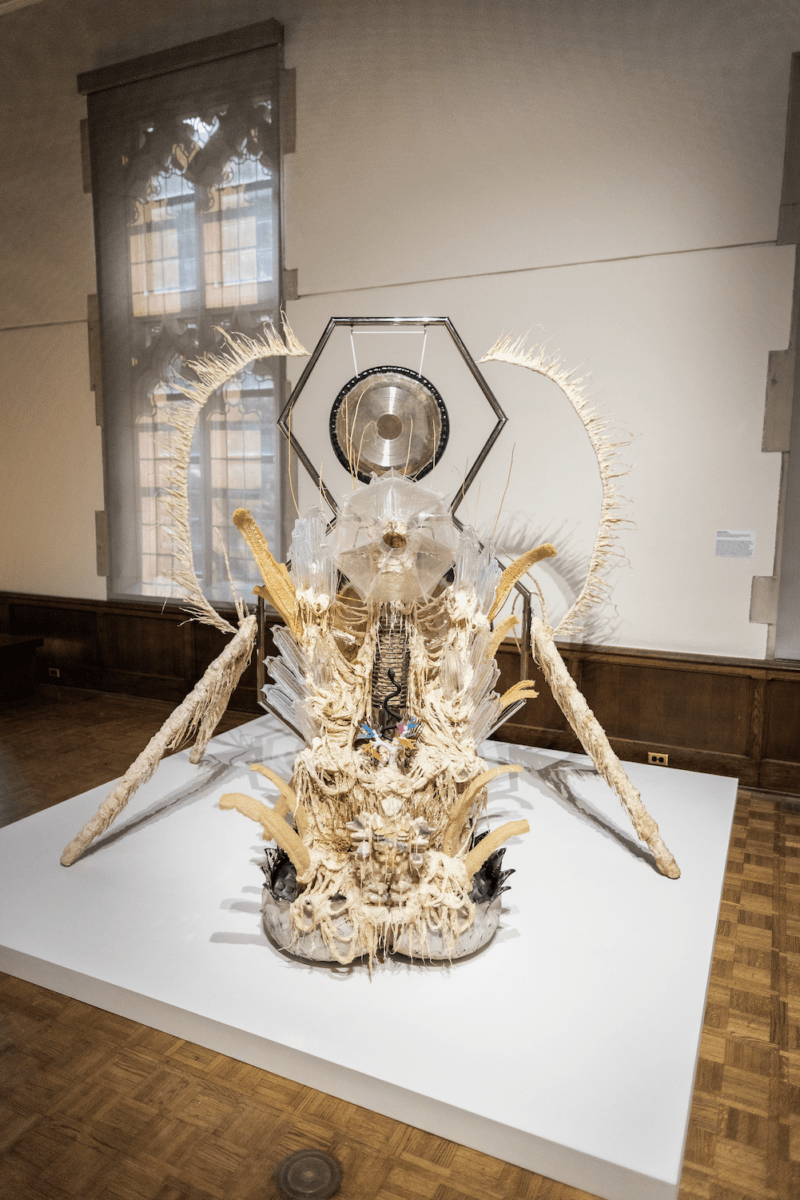

Guadalupe Maravilla’s “Disease Thrower #16”, faces the viewer upon entry, a large incredible sculpture made from materials that shift outside of understanding, which also offers healing and restoration. The eye races to the center of the gong as the first recognizable object; conjuring visually radial sound without sound through the piece and throughout the space. “Disease Thrower” gives the feeling of running up and down a large mammalian vertebra, through a prehistoric yawn. Made small we walk delicately amongst the shapes, both slumping and protruding, that spark and ooze texturally running all together. The imperfect symmetry creates the quality of being in the presence of a large living creature regarding you with vertically stacked eyes. The symmetry also belies that elements of the piece were collected on a journey. The artist retraced his migration route from El Salvador to the US; visible is the uneven symmetry of two journeys taken at different points in time. The work is a shrine, becoming the destination of the pilgrimage itself, once Maravilla returned and assembled it, which then completed the journey.

Installed in the back of the gallery, Mary Ann Peters’s three illustrative paintings on clay board document scenes on a silk factory floor in Syria in the 19th century. These particular women were chosen by the artist due to their success in negotiating with the French factory managers to get better wages and working conditions. There is a corresponding sculpture “impossible monument (the threads that bind)” which is made up of silk and the materials and tools that go into weaving it. Like Gbadebo, Peters uses materials that are the topic of the piece, however, the silk feels inactive, beautifully constructed but simply that. To activate the piece the artist has printed the names of the women workers on the silk. A sparse connection to the physical, dynamic nature of these women’s work both in the factory and in their organizing.

A lot of contemporary stake is put in names. A name can become a rallying cry, shorthand for a moment in time, a poem, a song, a sound. This is when a name transcends its original purpose to become a word, a symbol. There is power in symbols. But without this resonance, a name is a label, that does not bring us any closer to knowing or understanding them. A name without meaning is easily forgotten. That’s the true sadness here, which is that providing the name is meant to monumentalize, but a name alone is thin work and not enough.

Ken Lum’s piece, “The Recounting of the events and experiences in the life of Yashir Khorshedas” well relies on a name. A gigantic letterpress print made of short 19th-century style sentences that spell a portrait of a composite historical character after their death. The piece is less about this individual fictive character than about illustrating the concept that working-class people are memorialized differently than the ruling class throughout history. It highlights that disparity and presents and follows through on this thesis, but goes no further than this. “The Recounting” gestures towards monumentality with its size, but it felt more like an illustration of the idea, rather than an expression of it.

The seven shallow remains of a staircase of “Remain, piece of Balcony Baluster”, another piece by Gbadebo, are lined up in a delicate row. Each baluster like a family member, steadfast but at variable states of wear, was originally created in 1848 by John Spann and Anderson Keitt, carpenters related to Gbadebo. The balusters would have originally held up a balustrade, a support for use of the staircase, touched daily by many hands. Gbadebo’s desire once again comes through, to feel materials that her ancestors built, planted, and harvested. A deep yearning pushes through the fabric of time and space to touch what they have touched, which the artist makes real and possible through creating and assembling these artworks. I feel the hands and the voices of Gbadebo’s family and ancestry through her works, I do not know all the names of her family. I only know what she has shown me, which is more communicative and powerful than a list of names could be.

Songs for Ritual and Remembrance holds some impressive and moving work. The writing done by the curator Emily Zimmerman is exceptionally strong in creating a deeper understanding and engagement with the work. Each of the artist’s processes is so specific, that knowledge deepens the connection already created by the sensory experience of viewing. I found myself more deeply engaged with the work rooted in personally uncovered materials, connecting to senses of memory rather than the language of history.

Songs for Ritual and Remembrance, Arthur Ross Gallery, to Sept. 17, 2023