William Edmondson: A Monumental Vision, on view at the Barnes Foundation through September 10, 2023, is the largest exhibition to be held in decades outside Nashville, where the artist worked; and is cause for great celebration. While Edmondson’s sculptures are small, the term “Monumental” in the title acknowledges the artist’s place within American art, and suggests that his body of work is a counter-monument to African American communities in the Jim Crow South that were unacknowledged in public monuments.

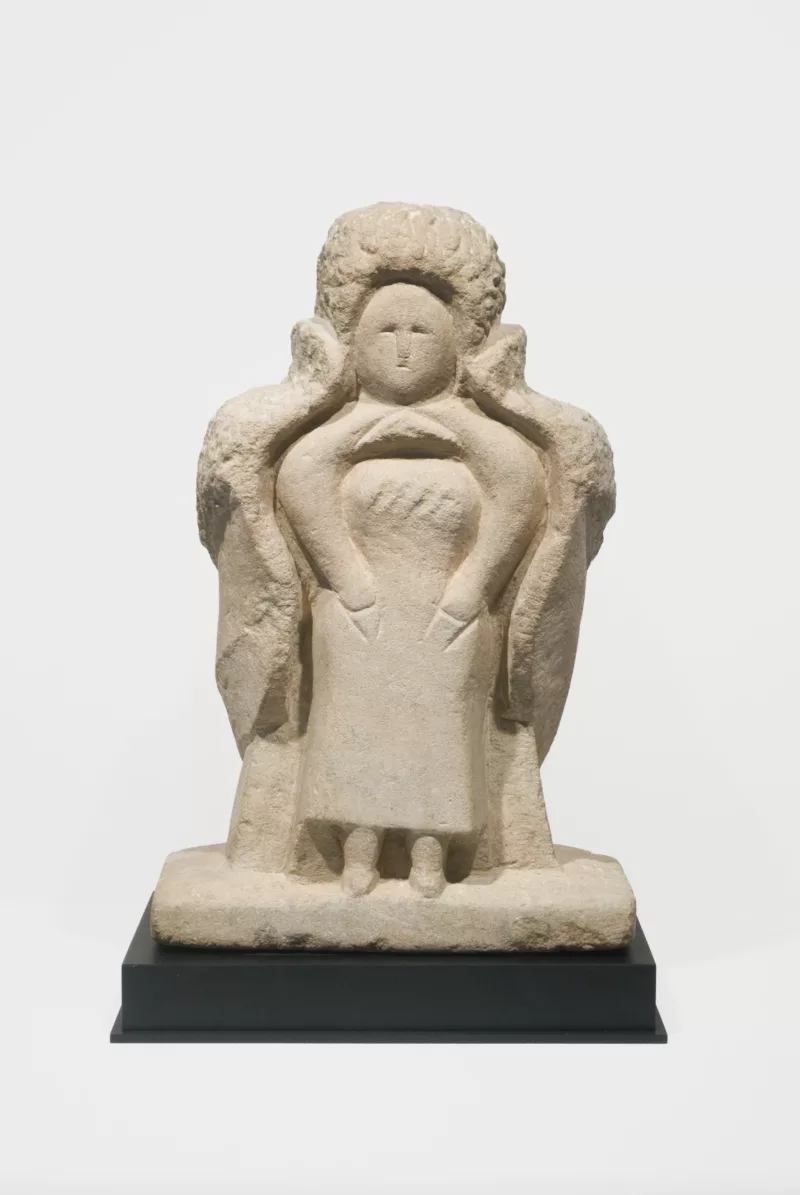

Edmondson took up carving in limestone in 1932 at the age of 58 in response to a divine calling, and faith was central to his work over the nineteen years he made headstones, pulpits, garden fittings and figurative sculpture. The Nashville artist was a respected figure among his neighbors and supported himself through sales to his local, African-American community, which extended in Tennessee beyond Nashville. His initial carvings were tombstones, two of which are included in the Barnes exhibition, as are several birdbaths and pulpits. He often worked with repurposed blocks of limestone intended for other uses and left their blockiness visible. The suggestion of life within the still-evident constraint of the blocks is central to Edmondson’s vision and skills.

Edmondson’s subjects include humans, animals, and Biblical subjects including numerous angels; all have generalized forms and small features that rarely reveal individual temperament. They are marked by the artist’s personal sensibility of forms and proportions and his great subtlety in using the smallest of details to indicate a foot appearing beneath the drape of a skirt, the texture of hair or fur, or a particularity of clothing that situates his figures. He carved people singly or in pairs and some, such as a crucified Christ (with raised arms as in African American evangelical worship), the angels and preachers, have obviously religious subjects. His animals are largely the sort the artist might have encountered during his childhood on a farm: horses, lambs, squirrels, rabbits and birds; some of the birds represent doves and they, along with the lambs, certainly had religious connotations. His work conveys a sincere respect for his subjects which is consistent with Edmondson’s faith.

Scholars have identified crucial aspects of the artist’s work and subjects within the culture of Southern African American communities and African traditions that survived the diaspora. These include the centrality of the church within communities and the role of preachers in representing them; respect for other educated figures who serve their communities, such as nurses and teachers; and traditions of house and yard decoration and grave markers. They have also tied many of Edmondson’s subjects to folklore, suggesting that rabbits, which he carved often, represent Br’er Rabbit, a trickster figure who outwitted his foes by misdirection, and that many of the small animals, such as foxes, possums, and terrapins are found in Uncle Remus stories, and that both these folk tales and favored Biblical stories have heroes who are liberators.

A few of Edmondson’s subjects are identified as well-known people: the exhibition includes two sculptures of Eleanor Roosevelt, who was notably supportive of African-American causes and who visited Nashville along with the President in 1934, and a boxer, a subject Edmondson carved multiple times, which might represent Jack Johnson, who became a hero among African-Americans when he beat a white opponent to become world champion in 1910. Several of the two-person works are identified as “Martha and Mary,” but most of Edmondson’s titles are more recent than the artworks and may represent choices of their collectors.

The exhibition includes four anomalous subjects. One is a mermaid in profile, whose forward-looking face gives the sculpture a resemblance to a ship’s figurehead – she might refer to a folk tale, “The Devil’s Daughters.” An absolutely marvelous “Noah’s Ark” in the form of a blocky, two story house sitting on two uncut stones, was photographed in Edmondson’s yard on a high, stone base and might refer not to the Biblical story but to a Nashville church named for it. The third is a nude man lying on his back, which is marked with hieroglyphic-like cyphers that have not been identified. It was commissioned by a neighbor and friend of the artist’s, Sidney Mttron Hirsch, a playwright who had mixed in artistic circles in Paris and New York before returning to Nashville. Hirsch had a serious interest in the Ancient Near East, mysticism and non-Western religions and was a member of a poetry group, The Fugitives, that formed around Vanderbilt University. We don’t know whether Edmondson had access to Hirsch’s library. But Hirsch’s position as a Jew in Nashville would have circumscribed his professional and social life beyond artistic circles, as Edmondson’s race much more rigidly limited his. He became significant to Edmondson’s reputation since through his friends within Nashville’s Jewish community the artist’s work was seen, collected and photographed by the photographer, Louise Dahl-Wolfe, who brought it to the attention of Alfred Barr at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

The fourth anomalous work, identified variously as “Seated Nude” or “Nurse Wooton,”

is shown in three variants. The curators identify them as satirical depictions of a supervisor during the artist’s long period of work as a hospital orderly, showing her sitting on a toilet; they suggest that these reveal Edmondson’s sense of humor. The subject, which has a prominent place in several photos of Edmondson’s yard and studio, makes a jarring contrast with his other depictions of women, and it is hard to understand why he thought it would find multiple buyers; an artist making his living by carving wouldn’t have wasted three pieces of stone for a subject that was entirely personal.

The Museum of Modern Art exhibited Edmondson’s work in 1937, which brought it to the attention of an entirely new audience which was monied and used to the conventions of modern art, and it attracted new buyers. Edmondson was unphased by the attention. Barr’s interest in the work reflected that of modernist European artists in the work of children, folk artists, the mentally ill, tribal cultures and others working beyond what they considered a vitiated European academicism – all of which is generally termed “primitivism.” The subject of an interest taken by urban elites in artwork by people of very different cultures has, and continues to be fraught with questions of imbalances of money, power and access to media.

The Barnes is exhibiting photographs by two artists who photographed Edmondson’s work, Dahl-Wolfe and Edward Weston, and essays in the catalog address the reception of Edmondson’s work.

The Barnes has taken significant efforts to present Edmondson “on his own terms,” both in terms of installation and through a dance commissioned from visual and movement artist, Brendan Fernandes. “Returning to Before” is meant to suggest a further, embodied way to approach Edmondson’s sculpture and to think about its place within the museum. The gallery reflects the artist’s display of work in his yard, which functioned as a showroom. The sculpture is primarily placed on two large platforms in the gallery with a third in the center which was designed for use during the performances. The dances were choreographed by Fernandes and will be performed by four dancers, on Saturdays at noon and 2:00 pm through the remainder of the exhibition.

William Edmondson: A Monumental Vision is on view at the Barnes Foundation through September 10, 2023.