Photo: Courtesy of the Artist

My first brush with David Kettner’s work was seeing reproductions of them online. They made me laugh and then just as quickly a sob caught in my throat. Who is this guy, and how did he do that with so little? I found some answers when I saw an exhibition of his work at Arcadia University’s Spruance Gallery.

David Kettner, Philadelphia artist and professor emeritus at University of the Arts, has been exclusively making collages for the last 10 years. His source materials include vintage children’s coloring books, Victorian etchings, Japanese prints, botanical prints, bits of wallpaper and other whatnots, which he then minimally modifies.

This survey exhibition includes 27 works spanning more than half a century. The pieces range from early paintings and drawings to a selection of his recent collage work. More of the collage work is available in a handsome monograph titled After the Fall that was published as a companion to the exhibition.

At first glance the collages appear to be simple remnants lifted from the past: cheaply printed amusements for children or rescued book illustrations. Give them a chance and they surprise you with a depth that resonates across the divide we think of as childhood innocence and adult experience. What happens when we color or cut outside the lines? What would childish scribblings reveal if we looked at them with an open mind? The exhibition traces how Kettner came to this open way of thinking and looking. We see the rigor of his earlier representational work shift to explorations of how to capture the intangible.

The early works include meticulous drawings and paintings that demonstrate Kettner’s keen powers of observation, his impressive technical facility, and a considerable stick-with-itness. In one, “Self Portrait #2” from 1975, the artist’s likeness is skillfully rendered in pencil. The disembodied face has a deep modeling that gives it the impression of emerging from the flat picture plane. It is the second of a group of six, each taking between 40-60 hours of drawing and looking in a mirror to create it. The materials are listed as “Graphite pencil on cameo paper.” Cameo paper is an ivory-colored clay-coated paper. Maybe it’s a punny coincidence that Kettner selected that type of paper to make his drawn appearances, but after seeing other work of his that is deeply considered and slyly playful, I wonder.

The exhibition maps the routes Kettner took to find his way to the later collages. Next to the drawn self portrait from 1975 is “Self Portrait” from 1986. It is an oil and acrylic abstraction on two joined panels. The piece uses dots and lines in an improvisatory way. Placing the self portraits side by side, you see how much has happened in the intervening decade. Kettner had stopped working figuratively in the period following “Self Portrait #2”. In the later self portrait, figuration is hinted at, but the painting style has become gestural and improvisational.

Photo: Sam Fritch

To make sense of the radical shift we can look at another set of works titled after a music composition by Johann Sebastian Bach. Kettner refers to these works as transcriptions. “J.S. Bach, Cantata BWV 12” from 1979 uses a four-dot system painted in casein on Masonite to create a complex pattern that scrolls mysteriously but pleasantly across the horizontal 31” x 61” picture plane. In this predominantly dark colored work, glints of white dots create a cryptic periodicity that conveys Bach’s structural interplay of melody, harmony and bass.

In the other painting titled “J.S. Bach, Cantata BWV 12” dated 1984, Kettner uses a network of interlocking rectilinear shapes that imply a jazzier spatial depth. White still pops out from the darker colors, but now in a vertical tumble over four joined canvases with the dimensions 120” x 90”.

Kettner has noted that around this time, he watched the film, The Mystery of Picasso, by Henri-Georges Clouzot, and that the film had a deep impact on him. The film shows Picasso’s playful and improvisational approach to making art. In a transcription of a panel discussion about the exhibition at Acadia, Kettner explains the impact: “It struck me basically, you know, overwhelmed me, and I thought I’d had enough of paintings that were planned ahead of time, including the palette colors all in jars. And then, you know, tracing the whole thing out and then filling it in.” It was after this that Kettner made the radical shift seen in Self Portrait from 1986.

I watched the Picasso film, and a quote by the artist’s son, Claude, about his father articulates the magic that happens in the process of making and viewing art: “People always seem to think that art should not be fun. I mean this is completely ridiculous, of course. And my father thought that his art was quite serious, but some of the things that happened while he was doing it were fun for him because he discovered things in him that he did not even know were in him. So that’s quite a giggle in a way, and it’s not just for giggles, but to tickle the mind. To make you see something that you would not see otherwise.”

After this we see Kettner’s work opening to other possibilities. He is still concerned with formal qualities, and that analytical approach to transcribing experience is still there, but he welcomes happy accidents, unplanned detours and unexpected collaborators.

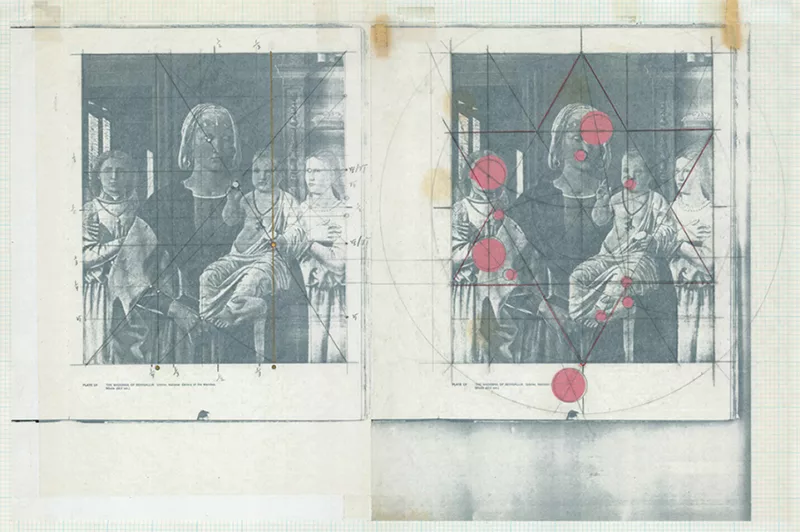

The analytical approach to musical composition has a mate in works where Kettner decodes visual compositions. An example is “Piero 1 & “Piero 2” from 1990. In this diptych Kettner shows two photocopies of a painting by Piero della Francesca. The side-by-side copies have tracing paper overlays. Both overlays have graphite lines exploring the compositional structure. The one on the right, however, includes red circular stickers. These we find out were placed there by his young daughter, instinctually. By examining the placement of the dots, Kettner deduces something that had eluded him on his own and uncovers a compositional arrangement in the shape of a 6-pointed Star of David.

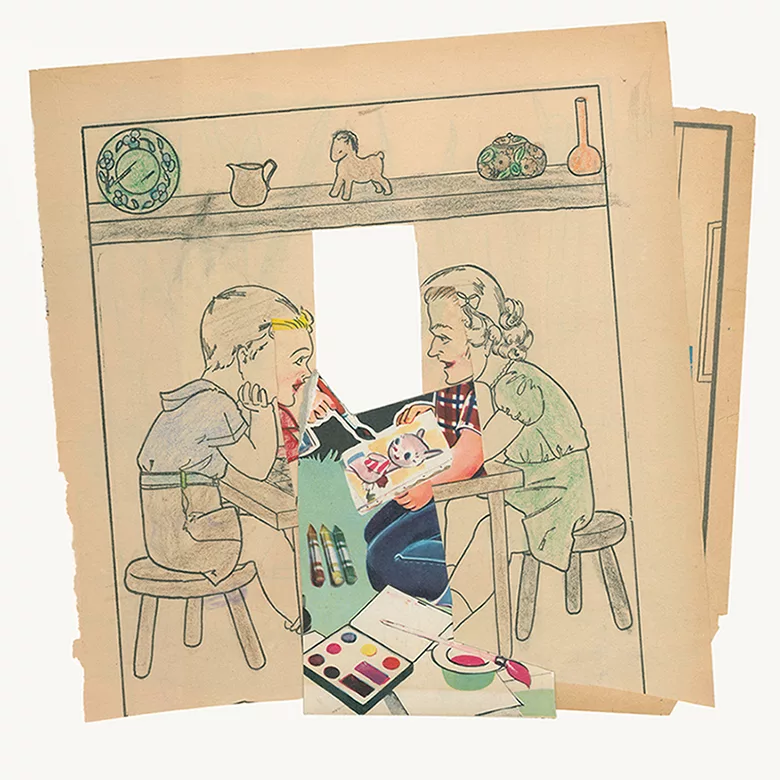

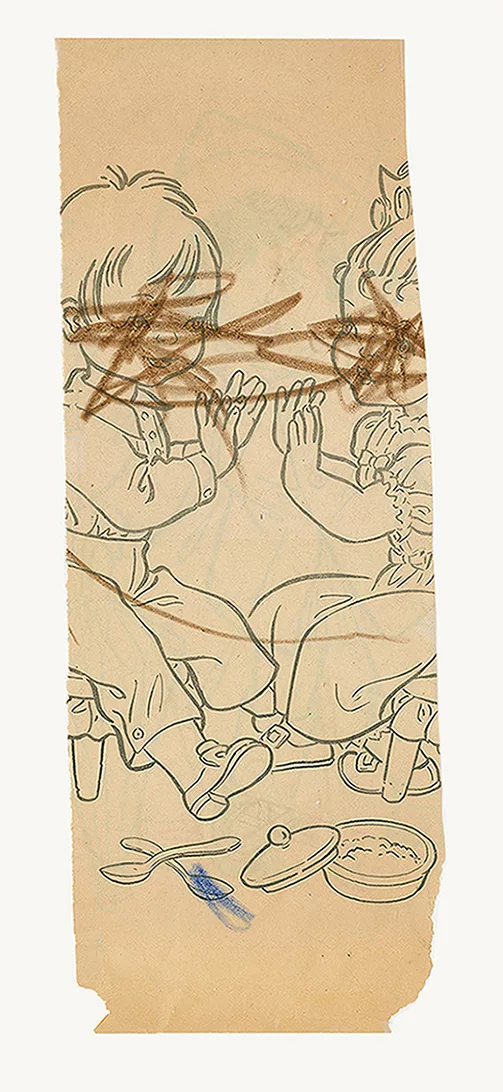

It seems that this type of interaction with his young daughter is not an exchange of information but an exchange of understanding. Kettner’s work takes off in a direction that questions what else we overlook. For example, take coloring books made for children. They start to look suspicious when singled out. What information do they impart to kids, and what do kids get from them?

The materials in “Pat-a-Cake” from 2017 are described as a “Coloring-book page fragment with child’s crayon markings.” This fragment consists of two children seated close together facing each other. They have interrupted a shared meal of gruel, as evidenced by the abandoned bowl and two spoons at the base of the image, to engage in a game of clapping hands with each other. What I enjoy about Kettner’s intervention is how he narrows the focus in the work to the parts that are most important to the child who consumed this piece of culture. Clapping games are usually accompanied by a rhyme. The child, rather than coloring the children’s bodies and clothes, supplied this vital missing element by drawing the verbal exchange as a scribble of lines connecting the two children’s eyes, mouths and ears. The child reminds us of the interrupted meal and anchors the image visually by coloring a dollop of gruel in one of the spoons, creating an inverted pyramid.

Most of Kettner’s collages involve combining multiple images. In “Canary” from 2022 two images appear to be taken from the same source whose images have borders. The skewed top border is the clue that tips us off that something is afoot. In a nod to Surrealism, Kettner creates a chimera by seamlessly joining a jar colored yellow at the head and shoulders of a caged bird. It’s a sleight of hand, but one that honors the child’s world where a jar labeled “Blue” is colored purple, and the atmosphere inside the cage is suffused with a red and orange vapor.

Kettner’s efficient, minimalist approach to his choice of materials and how he combines them supercharges them. “Fragments of a 19th-century steel engraving and a botanical print” are listed as the materials that Kettner used to depict a metamorphosis in “The Naturalist” from 2023. I find it both a silly and touching portrait. In it, we see a Victorian gentleman in a greatcoat whose head and body have been supplanted by triadic vegetation. A lovely, swishing diagonal of leaves and stems joins the man’s resting arms. The vegetal swag supports stalks with alert flowers and radiating beans.

To me, this and Kettner’s other collages offer a slant kind of truth. The kind that “must dazzle gradually” as Emily Dickinson wrote. You can’t simply tell people to stop thinking in simplistic terms of black and white, us and them, man versus nature. But you can gently prod and tickle them into seeing things differently.

I recommend the catalog, “David Kettner: After the Fall” for further investigation of this artist. It is a large format catalog that includes an introduction by Richard Torchia, the curator and editor, a conversation between Kettner and a fellow collagist John Stezaker, a seven-part consideration of Kettner and his work by Eileen Neff, a former teaching colleague of Kettner’s at the University of the Arts where Kettner taught for 43 years, and reproductions of 66 collages. Open the book to any of the collages and you’ll see visual puns, conundrums and mashups, often with psychologically charged slippages.

The exhibition David Kettner: Selected Works, 1968–2023 is on view at Spruance Gallery, Arcadia University until December 17, 2023.