Do not pay the ridiculous $30 admission fee to go see a sketch from Vincent Van Gogh’s “The Potato Eaters” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Go on the first Sunday of the month for the pay as you wish day. Don’t like children? Every Friday evening from 5-8:45 pm is also pay as you wish. The price of admission comes with the voyeuristic opportunity to watch many awkward first dates go down in flames. I’ll venture further, in case any upper management working for the museum is reading this (doubtful), “Give locals a discount!” I’m guessing if their own employees have to file a grievance over longevity pay after striking in the fall of 2022, the average citizen of Philadelphia won’t fare much better.

That said, you heard right, Van Gogh’s “The Potato Eaters” is on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, right now, a study, that is. Still, all you Vincent-heads out there must make the pilgrimage to view, “what is,” by His own admission, his finest work, a masterpiece, “The Potato Eaters” (preliminary sketch).

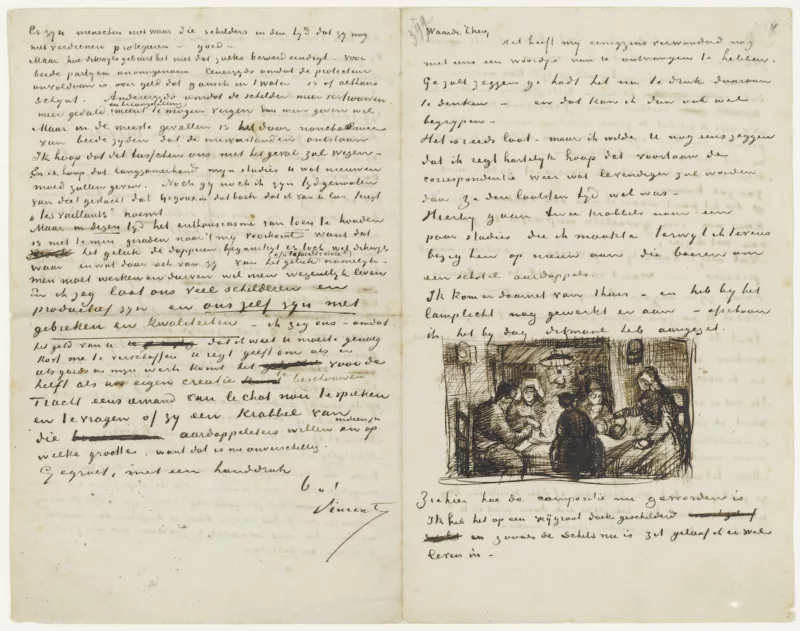

All artists should read The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh – to which, the drawing on display at the PMA was attached – in a letter to his brother, Theo – an art dealer and Vincent’s primary benefactor. The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh give us a rare comprehensive behind-the-scenes viewpoint of an artist in the late nineteenth century, an artist who is an articulate writer, well-read and versed in art criticism of the time as well as in literature. He also shares, since then only writing to his brother, intimate details of what it’s like to be a struggling artist. Oh and also, he’s one of the greatest painters who has ever lived.

Ok, why is “The Potato Eaters” so important? I mean, it’s kind of ugly. For sure when you think of Van Gogh you think, “Starry Night”, “The Bedroom” or his many studies of sunflowers: Bright, cheerful color, a celebration of the beauty of life. Beneath all of those works is where, like the potato, it all began, in 1885, in Nuenen (at his parent’s house, where all great artists start their careers) with “The Potato Eaters.”

“If I do better work later on, I certainly shall not work differently than now, I mean it will be the same apple, though riper; I shall not change my mind about what I thought from the beginning. And that is the reason why I say for my part: if I am no good now, I shall be no good later on either..” – Vincent Van Gogh, letter to Theo, Nuenen January 1885 Source: The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, Edited and Introduced by Mark Roskill, First Touchstone Edition 1997

In a short five years from sketching the “The Potato Eaters,” Van Gogh will be gone. He dies on July 29th 1890 due to circumstances that have been disputed. In five years he painted 750(ish) paintings, thankfully, to be spread in collections across the globe so that everyone gets a chance to look at, in person, a Van Gogh. Five years! He had committed himself to being an artist just a few years before painting “The Potato Eaters.” After failing as a school teacher, preacher (discharged for being overzealous), bookkeeper, art dealer, he was, at 30 years old, a failson. For a year prior to painting “The Potato Eaters” Van Gogh drew.

Aside from his primary inspiration, Millet, Van Gogh loved illustration (comics). He often references Honore Daumier among many other illustrators. His penchant for drawing may have been encouraged foremost from his lack of funds for paint. Aside from financial concerns, in his letters to Theo he remarks that drawing a scene thoroughly is essential in capturing the composition so that later a painter could commit more fully to the immediacy and emotion of their palette. “The Potato Eaters” was a large-scale canvas executed in a 3-day painting marathon. So, his preliminary sketches were a vital part of his process. Draughtsmanship was Van Gogh’s greatest tool and it shows in his paintings. His brushstrokes act like cross hatching, their aggressive and sure expression is what he became known for later in his paintings. You can appreciate this in his “The Potato Eaters” sketch. How often do we get to see greatness be born in an artwork?

In “The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh” you have followed him through to this point from being lovesick, then thoroughly consecrated to God, then, a painter. His oft-made references to bible scripture fade into descriptions of color in a landscape. Van Gogh found God in nature. He saw God in peasant life…much like Tolstoy’s Konstantin Levin. As he highly esteemed the peasants he aimed to paint, he also approached them as an artist – that is as an outsider. Where Millet achieved, a peasant that appears to be “…painted with the earth that he is sowing.” Van Gogh received criticism from his peers for figures that appeared to be awkwardly posing. In the end, Millet was a peasant and Van Gogh was from the city. Van Gogh was a poser.

“The Potato Eaters” comes across as a caricature, like Adriaen Jansz van Ostade’s peasants, who he mentions in his letters to his brother.

I’ve never been given the chance to see “The Potato Eaters” painting in person, but I imagine his palette is strong. Van Gogh, influenced by Millet, Corot and Delacroix, was after the light in the darkness. The year leading up to the “Potato Eaters” he was reading Delacroix’s color-theory by Charles Blanc. He had painted many heads, cottages in the moors at sunset, weavers, sewers and of course, potatoes. These studies were executed under a cloud of his own tortuous self-doubt. In conjunction with receiving very little encouragement for his work, he anticipated his painting would come across as offensive to his peers. In July of 1885, he would write to his brother in reference to the Potato Eater-haters, “And who were the persons that had suppressed and refused Millet? The art dealers, the so-called experts.”

“The Potato Eaters” is Van Gogh’s masterpiece. I wish I could see it in person, but there is on display in the PMA’s Resnick Rotunda a still life of flowers where I can imagine the palette that Van Gogh was after. Painted the same year as “The Potato Eaters” the painting depicts a bouquet of asters and marigolds (contrary to the title “Still Life with a Bouquet of Daisies”) in a dark room. Your eye travels across the canvas of the darkest pinks in shadow that seem impossible to paint to deep cobalt blues, a sliver of cadmium red, bursts of tinted yellow, orange, greens so close to brown only shown in contrast to the browns and grays in the background, then of course the brushstrokes which bring forth form, perspective and focus. It’s an exciting painting, where even the shadows have light. I’m very lucky to have seen it.

“There is a school — I believe — of impressionists. But I know very little about it. But I do know who are the original and most important masters, around whom — as round an axis — the landscape and peasant painters will turn. Delacroix, Corot, Millet and the rest.” – Vincent Van Gogh, Letter to Theo, Nuenen April 1885

In the hallway leading up to Van Gogh’s sketch of the Potato Eaters there are on display two paintings I think Van Gogh would really like, Jean-François Millet’s “Bird’s Nesters” & Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot’s “Night Landscape with a Lioness.” Both were painted at the end of the artists’ lives, where Van Gogh also began his short life as a painter. Nightscapes. Millet’s “Bird’s Nesters” nearly makes me want to cry when I stand in front of it. If it weren’t in a hallway, I probably would. (Full disclosure: the last painting I cried in front of was “Starry Night” in 2019.) ”Bird’s Nesters” is a childhood memory of Millet’s where children scare out pigeons from the fields using torches of hay and club them to death. This little bit of protein was like ice cream on a hot summer day to a poor peasant in the 1800s. A scene so enigmatic could only be painted because he was there. Corot’s Lioness in “Nightscape with Lioness” stands against an orange sunset surrounded by expressive brushstrokes of darkness, echoed in Van Gogh’s own descriptions and paintings of the moors of Nuenen. A lion is standing alone against the setting sun. The simple gestures in this painting, with its scratched surface and expressive nature, display where impressionism was being born.

For further reading I recommend Simone Weil’s “Gravity and Grace,” another peasant wannabe, as Van Gogh seems to have been. After all, the whole point of all this is to say “to suffer is to be closer to God”…and make great art.

Van Gogh’s “The Potato Eaters” sketch will be on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through Spring 2024. For more painting, I recommend checking out “Of God and Country: American Art from the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection” (even if Sheldon was sitting on the Board of Trustees of the PMA during September, 2022, when the employees were on strike for fair wages and a safe work environment.) There is on display in this exhibit some extraordinary Purvis Young paintings. This exhibit runs through July 7, 2024.

[Editor] Andrea Kirsh covered Van Gogh at PMA in 2012, find that article here.