Tradition encounters innovation, and history intertwines with contemporary expression at the Philadelphia Art Museum’s captivating exhibition, “The Shape of Time: Korean Art after 1989”. Here 28 artists grapple with identity, both culturally and politically. Striving to locate themselves in the modern world, they weave profound narratives to redefine the future of Korean art. As traditional craft merges seamlessly with the daring strokes of modernity, the exhibition becomes a dynamic tapestry, stitching together the rich cultural heritage of Korea with the demands of the present.

During my college years, I had the opportunity to study abroad in the Netherlands, where my roommate was Korean. Through his enthusiastic stories, I gained a basic understanding of Korean history, language, food, and culture, all of which he spoke of with immense pride. The political landscape on the Korean peninsula has undergone seismic shifts since the end of World War II, marked by the division at the 38th parallel. In 1983, President Reagan met with the then-general and dictator President Chun Doo Hwan, and by 1988, a national Constitution was ratified. Since then, South Korea has experienced substantial growth.

Two blockbuster pieces welcome you to the show

I won’t cover all 28 artists in the exhibit but am highlighting the pieces that resonated with me. Approaching the gallery Sunkoo Yuh’s (여선 구) work, “The Monument for Parents” stands at nearly 12ft. Placed outside the galleries but at the entrance to the exhibit, Sunkoo Yuh’s sculpture reinforces its role as a protector and blessing for the exhibition space—a totem warding off evil spirits while welcoming good spirits and good fortune. The work by the Korean American artist was created during his residency in South Korea in 2013. His first time returning to his birthplace in 25 years and both of his parents died unexpectedly. The work became a tribute to his parents and a reflection on his experiences as a Korean American. The loss of his parents shortly before his residency and return to South added a layer of mourning to the artwork, making it a poignant expression of cultural identity and personal history. [Ed note: Read Libby’s 2007 review of an Art Alliance exhibit that featured many works by Sunkoo Yuh https://www.theartblog.org/2007/10/juicy-sunkoo-yuh-at-the-philadelphia-art-alliance/ ]

Entering the gallery you are met with a 32 ft photograph backed by a wall of light. Jung Yeondoo’s (정은 지) “Euji Theater” is a light-hearted even playful piece looking onto the mountains of the DMZ creating a cognitive dissonance. There are 13 named observatory towers along the DMZ much like what the viewer experiences. In this image of the Euji observation deck is a kaleidoscopic collection of characters inhabiting the view. The scale of the image meshes well with the scope of its ideological context.

Disappearances and Subversive Embroidery

Juree Kim (김주 리) created “Evanescent Landscape – Hwigyeong: Philadelphia” to represent an area of Seoul that her studio used to be in. The city of Seoul bought the housing to create new towers and buildings as a sense of progress. The artist pours water on her unfired clay sculpture and it slowly disintegrates during the duration of the show and by the end it will be rubble. The photographer AHN Sekwon (안세권) captured the demolition of the homes in the area. Over a series of months the neighborhood was purchased and then demolished. The remaining people did all they could to stave off the inevitable buyout. The work, “Disappearing Lights of Weolgok-dong I”, is the result of watching the change to hundreds of lives in real-time. It is gentrification on a governmental scale.

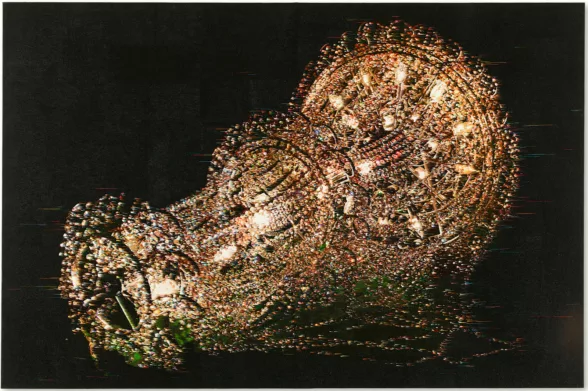

“What You See is the Unseen/Chandeliers for Five Cities” by Kyungah Ham (함경 아). Desiring to share the news of the world with North Korea Kyungah Ham considered, “we live in a digital world. I thought maybe what is the opposite medium of digital. And that was embroidery.” The news messages were embroidered into the work. “The first work was actually a failure; it was confiscated by the authorities.” Designs were covertly transported through intermediaries in China and Russia into North Korea, where skilled embroiderers produced them. The completed works then retraced the same clandestine route back to the artist. There are messages throughout the work all done in secret.

Covering Up and Rebuilding Buddha to reflect on culture and pop culture

“Second Surface” is a sculpture crafted by Kyeok Kim (김계 옥) using crocheted copper wires. The weaving process, born from the repetitive act of crocheting, creates a space shaped by the passage of time, evoking the layering of old memories embedding memories within the forms they create. “The Second Surface” represents a second skin that is both alien and familiar, shaped by a fusion of various memories and in defiance or a desire to attain a cultural beauty standard. Being able to see the work is reticent of camouflaging your surface, not to hide but to create a new shape, to create a new beauty. The beauty business in South Korea is fierce and the work asks you to redraw beauty.

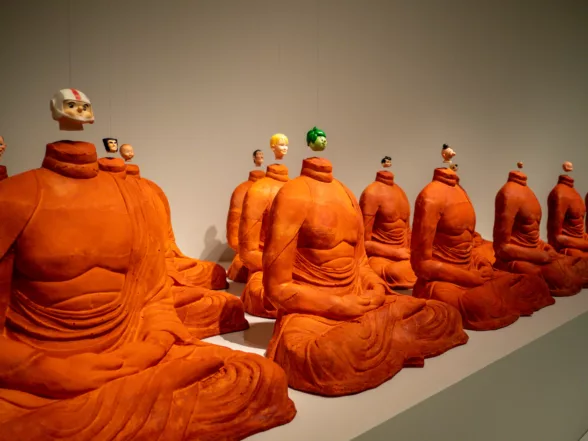

(마이클 주),2000

Urethane foam, vinyl plastic, styrene plastic, stainless steel wire, neodymium magnets, photo by Ryan deRoche

“Headless” by Michael Joo (마이클 주) is an installation of 16 sculptures modeled from the body a classic silently sitting Buddha with the head replaced by cartoon characters. The work builds from religious forms and begins to tackle issues like globalization and manufacturing in a playful way. Michael Joo explains that the toy heads used in the artwork are American, produced in Asia, and then sent back to the United States. The heads, familiar from his own childhood, hold personal significance and contribute to the piece’s accessibility. He emphasizes the importance of humor, recognizability, and a sense of value in his work. They range from Howdy Doody, Bert from Sesame Street, to characters from Rugrats.

Hair, Skin, Iron, Faces and Gay Culture, the present comments on the past

Yuni Kim Lang (유니킴 랑), “Comfort Hair – Woven Identity I” describes her work as most of her peers at this show in the context of identity and how elusive that can be. “There’s always conflict, never too American but never too Korean,” she says. “Hair was so iconic in symbolizing that of what was expected of me and what I was supposed to look like and all of the values I was supposed to carry. That felt too heavy and burdensome but also beautiful. This particular piece is a nest where it’s burdensome but it also comforts me.”

Kelvin Kyung Kun Park (박경 근) created a 3-panel video entitled “A Dream of Iron”. He tells the story of Korea’s many centuries of progress. From its Paleolithic history to a group of scattered whaling villages, to more recent developments like the steel industry focusing on shipbuilding, It covers laborers, becoming a G20 nation. The PMA’s gallerist, Elisabeth Agro, described it as “handmade, he stitched these scenes together. Learning about Korean customs and culture, this video teaches everything you need to know.” I was pleased that the video used the multiple panels to enrich and focus the story the artist was presenting. [Ed. note: Find our interview with Elisabeth Agro]

Byron Kim (바이런 킴) is showcasing 320 pieces from his ongoing work entitled “Synecdoche”. Each panel, measuring 10×8 inches, displays a skin tone, challenging a binary view of race and aiming to explore the breadth of variety between the skin of each individual. Kim notes that the work is often linked with a sense of coming together, but at PMA, it is categorized as anxiety, a facet he believes is often overlooked. Each panel is named after the respective sitter. This is an ongoing piece which now has over 600 pieces.

In the same room on the opposing wall is “Left Face” by Heinkuhn Oh (오형근). 7 large photos are expressing the idea of an image as a facade. Heinkuhn Oh feels that with the greater freedom after the political revolutions that the nation of Korea has faced greater anxiety than it did under authoritarian rule. With more freedom comes more anxiety and comes to the surface. Facing off against the “Synecdoche” work shows the anxiety of modern society. Museum Educator Cherish Christopher shares her connection to the artwork, expressing empathy with the depicted anxieties. As a younger person, she relates to the collective struggles of her generation in navigating societal expectations and the quest for a fulfilling yet sustainable career. Cherish, who identifies as femme, discusses the societal pressures on appearance and the challenging expectations placed on individuals. The artwork transcends cultural, ethnic, and racial boundaries, touching upon mutual feelings shared among human beings.

In the installation “Where He Meets Him, Philadelphia” by Inhwan Oh (오인환), an openly gay artist created this site-specific installation featuring the names of different queer bars and clubs in Philadelphia written on the floor using powder incense. Curator Elisabeth Agro explains that the artwork serves as a memorial to queer spaces in the city, preserving their history. Inhwan Oh draws on his lived experience, particularly highlighting the challenges of being different in a society deeply rooted in Confucianism and conventional norms. The incense isn’t being burned in the museum but the connection between the smell and memory is profound and emphasizes the significance of ancestral power, recognizing that individuals are containers of generations, holding knowledge, life experiences, and identities.

“The Shape of Time: Korean Art after 1989” through February 11 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art is a visual symphony that reflects the essence of Korean identity with contemporary art that pushes the boundaries of artistic exploration. The themes explored in this exhibition resonate universally, creating a connection that extends beyond cultural boundaries.