Photo courtesy of the artist.

Dark Matter: The Art of Anthracite By Andrea Krupp at The National Museum of Industrial History (NMIH) in Bethlehem, PA, is a small but inspiring exhibition of the artist’s latest work on climate change centered art. Fifteen carved anthracite coal works fill two cases near the museum’s entrance. It is an added treat to see the works in the context of this gem of a museum. The NMIH is a Smithsonian Museum affiliate, located within the SteelStacks Arts & Culture campus of the former Bethlehem Steel plant, an hour and a half drive from Center City Philadelphia. The museum includes permanent displays of industrial age machinery like a beautifully restored steam engine, artifacts from the silk industry, exhibits on the lives of local steelworkers, as well as changing exhibitions, like Dark Matter.

Andrea Krupp has been focused on exploring places and climate issues in her work for years through a variety of mediums. During an artist residency at The Arctic Circle, she made ephemeral work that she documented in photographs, including spelling out poems in coal from Pennsylvania that she carried in and out of Svalbard, Norway where the residency was based. Her deep interest in anthracite coal started several years ago. She worked with rare books in the conservation department at The Library Company of Philadelphia and curated an exhibition there called SEEING COAL Time | Material | Scale with materials drawn from its collection as well as works on paper she created with and about coal.

As a Philadelphia-based artist, Krupp was struck by the historical, cultural and environmental impact that a local metamorphic rock has had on a global scale. The sprawling Anthracite Coal Fields of Pennsylvania lay 90 miles north of Philadelphia in the Lehigh Valley. Mining it was a big, dirty, dangerous but lucrative business that brought people to the area for work, including children. (Look up Breaker Boys for just one of many appalling failings of the nascent industry in this country.) Pennsylvania anthracite was heavily mined in the 19th and 20th centuries and shipped all over the world. It is the only anthracite coal reserve in the US and accounted for 90 percent of the world’s anthracite. Anthracite is the hardest, purest and most efficient-burning variety of coal. As a cheap and efficient fuel source, it was pivotal in the success of 19th-century industrialization. Anthracite mining declined in the 1950s, but as Krupp’s work tacitly implies anthracite as a historical fuel source continues to influence our thinking and behavior around energy consumption and ecological issues. A century ago, we learned to pull the blackest black from the recesses of the earth and turn it into electricity to light the darkness. Krupp is now shining a light back onto those hidden energy systems and asking us to question the means of production and our expectations. Krupp uses coal to represent itself as well as gas and oil, the fossil fuels we have become dependent on in this time of global energy transition.

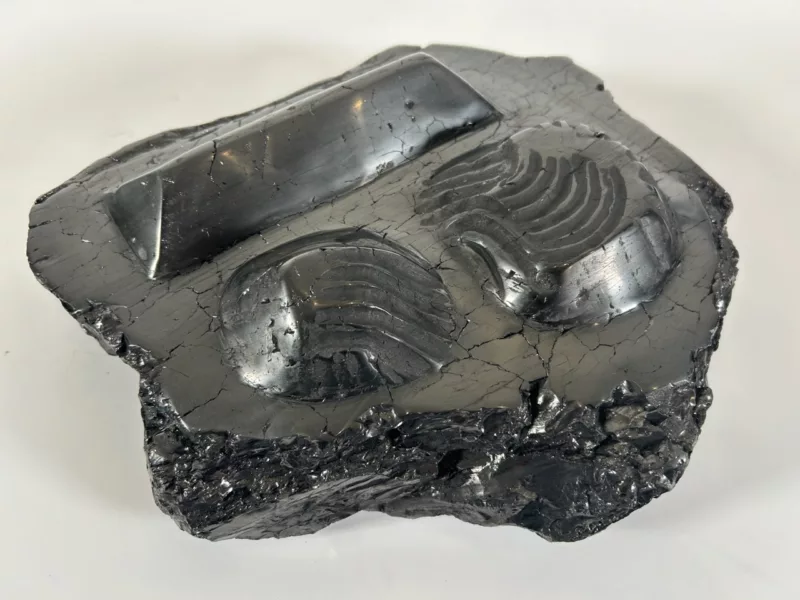

Krupp’s carvings in coal depict examples of how we have harnessed and harassed the material. By chipping and sanding blocks of anthracite, she has created models of stockpiles and culm piles, the latter being the anthracite waste material dumped near mines and coal ports. She captures the inherent geometry that occurs when loose material is piled and finds its stable state, the gentle sloping “angles of repose.” Through variations of surface treatment, she indicates the patterns of erosion that naturally occur. She scratches into the rock to draw the rail lines that encircle the mounds and depict the tracks used for transporting coal via rail from the Lehigh Valley into the City. She gouges into the rock the way miners pick their way through the deposits. The incised “Grotesques” recall ancient petroglyphs or fossils but are maps of mines. And she polishes the rocks to a smoothness that creates a bewitching black mirror surface.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

The pieces are curious lumps that are worth taking time with. They are self-referential; their subjects never stray from their materiality. The titles of the works hold clues, but even without them you intuit meaning through the surface treatment. Some parts that have been worked have a high glossy appearance, others have varying degrees of dullness, and finally there are the raw, jagged shiny conchoidal fractures that occur when the stone breaks.

I wasn’t familiar with anthracite as an art material. Roberta Fallon, The Artblog editor, mentioned the work of the Dufala Brothers, who have made beautifully crafted replicas of modernity in anthracite, such as an iPhone, vape stick, and tools of the trade like a hammer head and anvil. Andrea mentioned there is a rich local tradition of carving anthracite in Northern Pennsylvania, citing Charles Edgar Patience as a prime example. Patience, who died in 1972, was the son of a former breaker boy. He had a successful career as a sculptor, creating everything from small pieces of jewelry to life-size busts and even a church altar carved in anthracite.

Anthracite is a dirty material to work with. Krupp wears a mask and coveralls, and does all her sanding in water to keep the dust down, and yet that doesn’t seem to be a deterrent. In one of my conversations with her she said, “If someone has a spark of curiosity, anthracite will ignite it.”

Dark Matter: The Art of Anthracite by Andrea Krupp is on view at The National Museum of Industrial History through February 4, 2024. Krupp will present a gallery talk on January 28 at 2PM.