About the (re)FOCUS and FOCUS projects:

(re)FOCUS 2024 celebrates the 50th anniversary of Philadelphia Focuses on Women in the Visual Arts/1974, a citywide festival recognizing women artists. It is organized by Judith K. Brodsky and Diane Burko. As the project expanded, Burko and Brodsky invited Marsha Moss, the Philadelphia curator/entrepreneur/public art expert to work with them. Diane Burko is one of Philadelphia’s most prominent artists. Her work has been shown nationally and internationally. She is especially well known for her paintings about climate change. Artist, writer, curator, activist, entrepreneur Judith K. Brodsky founded the print center which is now The Brodsky Center at PAFA (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts).

The original 1974 festival was one of the first large-scale surveys of work by contemporary American women artists, signaling the inception of the American Feminist Art Movement. The documents for this 1974 exhibition are in the Philadelphia Museum of Art archives.

Initiated by Philadelphia painter Diane Burko, the central event of the FOCUS program was Women’s Work: American Art, 1974, a contemporary art exhibit financed by and held in the Museum of the Philadelphia Civic Center. Burko and Judith Brodsky formed a group that organized the 1974 FOCUS. Burko headed the steering committee and Brodsky, the finance committee. They were joined by other young professional women starting their careers in the visual arts who participated as members of various committees.

With over 150 exhibitions, panels, lectures, workshops, and demonstrations, it was one of the first large-scale surveys ever of women artists, curated by a distinguished group of women pioneer curators: Marcia Tucker, who would go on to found the New Museum, New York; Cindy Nemser, art critic and founder, the Feminist Art Journal; Adelyn Breeskin, the former director of the Baltimore Museum who at that time was the curator of painting and sculpture at the Smithsonian American Art Museum; Lila Katzen, sculptor; and Anne d’Harnoncourt, then, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art where she later became director.

(re)FOCUS will also include exhibitions, workshops, lectures, and panel discussions, among other events. One of these is a two-part exhibition at Moore College of Art and Design. Judith K. Brodsky and Diane Burko curated part 1 which brings artworks created by 82 of the original participating artists together in one space and part 2, where gallery director Gabrielle Lavin Suzenski, along with Denise M. Brown, executive director of the Leeway Foundation present new and recent work/s by Philadelphia-based artists who are exploring ideas of gender identity, representation, marginalization, social justice, violence, equality, and empowerment in their contemporary studio practices. The exhibits will be on view through March 16. The catalog for (re)FOCUS is available to purchase here.

The Interview

Susan Isaacs

In 1974, I was a student at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, but I was completely clueless. When I was at Boston University (1971-73), I took two art history intro courses and the modern survey. Not a single woman was discussed nor included in the textbooks. It never occurred to me that this was a problem, despite being a feminist. I was involved with the feminist organization in my high school. I went to see Betty Friedan when she gave her talk at the University of Delaware, before I could even drive. A bunch of us piled into a station wagon to go listen to her, and yet, I still did not see the connection between political feminism and art history, much less contemporary art.

Also, I didn’t live in Philadelphia. I remember going to a big show at the Civic center, which, no doubt, was FOCUS. I was 20 in 1974, but it didn’t stick in my brain because I was on a path to conquer academic drawing and painting, which was not natural to me. It took me until seeing the Judy Chicago show at the Brooklyn Museum in 1979, to realize that there had been and were good women artists, writers, and musicians worthy of attention and equal to male artists, and that I did not need to be an academically good painter. That experience (standing quietly in line like going to visit a holy place) helped me see that my own decorative painting, inspired by Fauvism, textiles, and non-western art was a feminist/political stance. I just wasn’t ready in 1974.

Judy Brodsky

This is interesting because it resonates with stuff that we will say, or that you’ve already heard from us, from me. Being introduced to feminism in the art world was something that happened to me through FOCUS. You’re talking about not being aware that there were no women artists included in art history. When I was growing up, I knew a lot of women artists. My father was teaching English at Brown University, but he also had a lot of friends who were visual artists—people the generation of Perle Fine, and their work was in the Rhode Island School of Design Museum. I remember seeing all these artists in that period, when I was a teenager, and they were in the early stages of their careers. So, I don’t think I ever felt that women were not being recognized as artists. However, when I got to Harvard and I took Fine Arts 13, which was the standard Art Survey course, it didn’t occur to me that there were no women artists in it, because it was history. I didn’t make the connection to the contemporary art world that I was in. And then also because I became a printmaker and there were many women printmakers. I still didn’t become aware of the exclusion of women from the visual arts disciplines which were higher up in the hierarchy.

Susan

In the early 70s, I read all the time for pleasure, but I was not an intellectual. I had friends who were, but I was not a deep thinker.

Diane Burko

I’m with Susan. I also was not a deep thinker, and I always have envied you, Judy. You know that because you grew up in such a rich intellectual world. I’m first generation American, you know. My father was super bright. He read 5 newspapers. There were no books in my house. It’s not a question of people not being bright. It’s a question of what their opportunities have been.

Susan

We had books, the NYTimes, travel, dance, and classical music, but the discussions were more political in our household, though I always took art classes at the Delaware Art Museum and in my public high school. We did have contemporary art on our walls. I purchased my first art book with babysitting money when I was about 16; it was a brief history of modernism beginning with David. I was also fortunate to study with Ed Loper Sr. for two years before I went to college. He was an excellent teacher of what I later realized was his own interpretation of the Barnes method and the work of such artists as Gauguin and Cézanne. But art school for me (at Boston University School of Fine Arts and then PAFA) was more about learning academic painting. I just muddled around on my own for several years after graduating, finally ending up c. 1979, being what I later realized was a Pattern and Decoration painter. But I didn’t know that movement even existed. I didn’t know of any of those artists. I was not reading Art in America. It didn’t occur to me to go to the library to seek out publications on contemporary art, and I had no money to purchase the magazine of course.

Judy

I made my own pocket money because my family didn’t have any money. It was a natural thing for me to be around the cultural world, but in terms of that era before professors unionized and got decent salaries, I didn’t have the money for a magazine or a candy bar, anything like that. But what I will tell you is that I went to Sunday school and Hebrew school. I went to Hebrew school, even though my father and mother were, I think, agnostic. My father would say to me, you can always think as if there is a God. Apparently, there was a German philosopher who had the theory that human beings can think as if there is immortality. So that was very comfortable, but at any rate I would always win the prizes. I’d get $5, for having written the best essay about something at Sunday school. I wasn’t buying art books at that point. I was buying records. With my little $5 bill, I would go to the music store and be able to purchase a Beethoven Symphony or something like that. It’s interesting how we both later realized that there was a [feminist art] movement out there.

Susan

By the time I realized that P&D was a movement its moment was over. I maybe could have been showing with Miriam Schapiro and all these other people, but it took me a long time to grow up artistically and intellectually, despite being surrounded by paintings and books. I am only now earning my MFA in studio art, after having an extensive career as a professor of art history and curator.

Judy

And I want to say something about that. It’s better now, even if you regret that you weren’t aware when you were younger, than to do it when you’re young and then have nothing later. One of the sad things about all the research that Diane and I have done over this last period on the 82 artists in the original exhibition at the Civic Center, is how many have disappeared from being active, or having accomplishments, and my heart really goes out to them. I’m delighted that we were able to get them for this show, so that they do have something that will document them. They’re not in books or anything like that, and of course some of them are famous, but a lot are not. While the original FOCUS was to include a catalog, it was never published, but there is a catalog for (re)FOCUS which will be available at Moore College of Art and Design.

Susan

In the late 80s and early 90s, I co-hosted and then hosted a radio show on the arts for eight years in Wilmington, Delaware State of the Arts, and Guerrilla Girl Frida Kahlo was on my show via the phone. She talked about how the successes that women artists have had were generally outside of major cities. As a curator, I have shown the work of many artists of color and women artists. I began curating in 1986, but mostly in the Mid-Atlantic region, especially Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Maryland, generally not in what are considered the high-end art markets where national and international careers are most often made.

Diane

You have always shown a lot of women artists.

Judy

I’m supposed to be doing a new book for Bloomsbury, and that’s a big thing in this book that is still not being addressed, the regional aspect of women’s art careers.

Susan

I think the support of the NEA is a part of that, because the NEA began to disperse monies outside of New York and other major cities. And that’s important, at least in providing a regional voice for artists, who often are women.

Diane

And that’s what we’re doing in these exhibitions.

Judy

We had an NEA grant in 1974, which we think was the very first NEA grant that went to a feminist art project. And now we have another one, which is really great.

Susan

How did the two of you meet?

Diane

We met through FOCUS 50 years ago.

Judy

And we’ve been good friends ever since. But that’s how we met. Diane, as you know, had gotten interested in doing something feminist in Philadelphia. Diane knew about the meeting of 350 women artists in 1972 at the Corcoran Museum of Art. It was the first time that women artists ever collected to talk about their complaints. Everybody talked about how women were discriminated against and protested the male dominated art world. Inspired by the Corcoran event, Diane invited some friends to a meeting, and then a call went out. The reason I responded to the call is because I was just starting to teach my first full-time tenure track job at Beaver College [now, Arcadia University] where Jack Davis was the chair, and he told me that the women of Philadelphia were doing something and suggested that I might want to find out about it. And so, as a good, obedient young assistant professor, I wanted to do what my department chair told me to do. I found out that there was going to be this second meeting. And I got involved.

Diane

And it was April 1973. Right? Here’s a little-known fact. I had the first meeting at my house, and I invited people who were well known in Philadelphia, and Anne d’Harnoncourt was there. And some friends of mine, and then we all decided that we should expand it. So we made this notice, and we sent it out to other women. Judy, here’s the part you don’t know. I was shocked when it was published in the newspaper, (The Philadelphia Bulletin). That was not my doing. All of a sudden, the whole world knew about this meeting we were having. I think we had it in the basement of the Education Department at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. We probably have the notice in the archives. But I didn’t know that it was sent to the paper, and I said, Oh, my God, who did this? Someone gave it to, I think Victoria Donahue or Nessa Forman, I don’t remember. And that’s how Jack heard about it, and Jack asked Judy to come. She comes to the meeting, and she comes up to me after and says, you know, I would like to get involved. I don’t know what happened, but we just clicked. And not only was Judy Brodsky involved, she was my right-hand girl. We ended up sharing the finance Committee.

Judy

I kid around and I say that the pile of papers was as high as I was when I was working out the budget for the NEA grant application. And it’s what really started me doing that kind of thing, and I actually went down to Washington and met with the people at the National Endowment for the Arts. I wanted to make sure that they understood what we were doing. Sometimes you can explain things when you meet with someone in person that you can’t do through a written application. And they didn’t have to do that.

Diane

And we did that, it really was the start of my activism in a big way.

Judy

Diane started me out really in feminism in the art world. And Diane is the reason we kept doing more stuff together, like the Women’s Caucus for Art. She was invited to be the third president of the Women’s Caucus for Art, but she was busy with her career and her teaching, and she suggested that I be invited instead. Diane is modest about the many skills she has besides her wonderful painting. We all thought “she’s a real leader,” which she is, and I would follow her to the ends of the earth. We named her the Queen Maker, because over the years, she has done the same thing with other women, saying “Oh, I have someone better than me.”

Diane

And did Judy Brodsky change the WCA. She made it national. I mean, you know Judy is a trailblazer. She’s done so many firsts for every institution that she’s involved with.

Susan

What are some of the outcomes from that first citywide FOCUS on women in the arts?

Judy

The immediate outcome was that everyone noticed. We were covered in the New York Times, in Art in America, Art News, and Arts. Every magazine in New York came to us. And it really was the first time for Philadelphia.

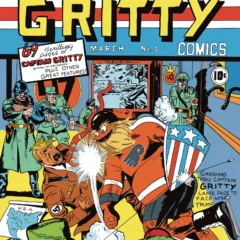

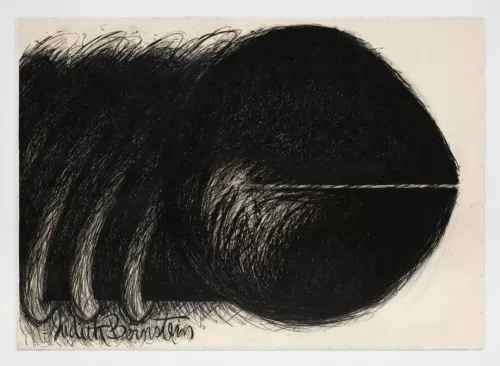

Then there was the Judith Bernstein incident. The Civic Center Museum director said if we didn’t take her work out of the show that he was going to take the whole show down, and we couldn’t do that to the 81 other artists. We did remove her drawing, Horizontal, from the show. And, Diane had a brilliant idea, which was a precursor really to the Guerrilla Girls because it was a performance piece.

Diane

The Button. At the opening, everyone wore a button that said, “Where’s Bernstein?” And you know, Judy, I didn’t tell you this either, because Judy and I don’t have time to really talk. All we do is stuff for FOCUS lately. But when I spoke to Joyce Kosloff about all this, she said, I don’t know if I remember what show that was. And then she asked, “Is that the one where we had the Judith Bernstein buttons?” That’s what she remembered, and it really was the first time that someone did a performance that captured people’s imagination for feminism.

Judy

It preceded by a decade at least, the Guerrilla Girls. But anyway, Judith Bernstein always says that was really the start of her visibility. It was the start of her successful career because the incident got such publicity that it catapulted her from invisibility to recognition.

Diane

And she is in the current show with a smaller piece, but we reproduce the one that she didn’t show on the wall label and in the catalog.

Judy

Ironically, that drawing is the one which the Metropolitan Museum of Art bought in 2022. It’s in their collection. The original FOCUS was one of the earliest feminist exhibitions, and it got a lot of publicity. It was the very first large scale one outside of New York city. There was one in New York just before that, but not one that large, and not one that involved all the other institutions in the city.

Diane

And we got a lot of mileage out of that. It wasn’t just the one exhibition. It was the whole city. It was cumulative. And it wasn’t just exhibitions. It was a film series. It was poetry readings. It was amazing, and it went on for just about three months. Marian Locks had three separate exhibitions from March all the way through to June.

Susan

What happened long term because of that 1974 exhibition?

Judith

All of us who were involved, it was our training ground, in a sense.

Diane

We cut our teeth working on the original FOCUS.

Judy

We ended up doing things on a on a grand scale from that point on and it’s not just Diane and me, but Thora Jacobson, who was the director of Fleisher Art Memorial for so many years; Penny Bach, who was director of the Association for Public Art in Philadelphia, Judy Stein, who became a nationally known curator and author, Ruth Fine, who was a curator for the National Gallery of Art, and , just to name a few. We were empowered by what we did, and so, from the point of view of all of us, we moved on into positions that enabled us to keep on having an impact on the art world.

Diane

And we kept in touch. I remember when Deborah Marrow came back to Philadelphia when she was on the board of the University of Pennsylvania. That was before she was the head of the Getty, but she already was a big shot at the Getty, and we kept up over the years. Some of us kept up really closely, like Judy Stein and Penny Bach and me. Ruth Fine, who went on to be a curator at the National Gallery; she’s relocated back to Philly, and she’s gotten involved again with us. She wrote one of the essays for our 200-page catalog for (Re)FOCUS.

Judy

The catalog is not only for the current show at Moore but includes a page for every single institution involved in (re)FOCUS. Whatever exhibition they’re doing, there is a write-up about it. There’s a photograph of what it is they are doing as well. And so they’re all getting recognition in the catalog and on the website.

Diane

We secured a grant for the catalog from Harriet Weiss, one of the outstanding philanthropists in Philadelphia’s visual arts community. She used to own CRW Printing Press. You know, Judy, I don’t know if you know this, either. All these little tidbits. She went to high school at Cheltenham High and was one of five young women who all went to high school at the same time and all five became makers and shakers: Mary Ellen Mark, Linda Brenner, Jill Bonovitz, Barbara Zucker, and Harriet Weiss. Do you believe it? It’s phenomenal. I don’t know what was in the water they drank, and they’re all the same age. They’re all 83 years old. So, there you go, and that’s something I know.

Judy

Wow.

The catalog will be available from January 26th. There are five essays.

We engaged in what turned out to be an extensive detective enterprise to reach out to the 82 artists in the original exhibition. Judith Stein and Ruth Fine were members of the 1974 FOCUS group. We invited them to write essays for this catalog because they wrote the primary materials for the 1974 FOCUS. We also invited Robert Cozzolino and Imani Roach to compose essays. Judith Stein actually did the essay for the Sandak slide set that was made for the 1974 Woman’s Work exhibition.

Diane

Oh, my God! Talk about the old days! Not everyone knows what Sandak means. I taught Art History so I know. [the Sandak company made the slide sets for teaching art history]

Judy

I tried to trace the slide set down—to make sure that we’ve got all the copyrights. Sandak went out of business in the mid-1980s which is also an interesting date—it’s about when we began to use digital images to teach art history. They were bought out by various publishing companies and those companies just lost track of the Sandak records completely. No one has any idea who’s got the copyright. At least I have my trail of emails. On each artist’s page we’re putting a plate of the work that is in the current show, but we are also putting a little image of the work from the Sandak slide set that the artist had in the original 1974 show.

Diane

We found one extant slide set in the archives at Rutgers University in New Brunswick.

Judy

That wasn’t completely pink.

Diane

There’s been a lot of detective work, and Judy gets the credit really for all the detective work that happened for the 82 artists in the show. That was more her doing than mine, but we share. We each do what we do best. One of my big tasks was contacting all the institutions.

Judy

As I said, a lot of them we had to trace down, and we’re missing four out of the 82. One is Luanne Keller. We had no idea who she was. We have nothing on her, not even an address for her on the loan form, because the Civic Center loan forms did not include addresses. Others not in the current exhibition for various reasons include Linda Howard, Katherine Porter, and Irene Moss. I feel badly about Irene Moss (d. 2012), who is one of the three founders of the Feminist Art Journal. We have a page for her in the catalog, and we have a bio, but we don’t have an artwork in the show because we could not find one that could be included.

Susan

When I look back at the lists of the artists in the original show, some of them are very well known today. I just saw the Alma Thomas show at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Others were Eleanor Antin, Louise Bourgeois, Barbara Chase-Ribaud, Elaine de Kooning, Agnes Denes, Joyce Kozloff, Lee Krasner, Yayoi Kusama, Joan Mitchell, Alice Neel, Louise Nevelson, Howardena Pindell, Adrian Piper, Faith Ringgold, Miriam Schapiro, and Pat Steir, to name just a few.

Judy

We have an Alma Thomas coming down to us from Albany. I finally found this small Thomas through Swann auction house. We needed a smaller Alma Thomas, not one of her huge canvases, because there was no way we could fit in 82 large works. I followed the auction records, and I knew that some small works by her had been auctioned recently at Swann. Through them, we got in touch with the various collectors who had bought them, and one collector finally, at the very end, said, “Yes, I will lend.”

Diane

We have a few pieces that are fairly large. We have a large-sized Alice Neel because she, of course, graduated from Moore College of Art. It’s really been an adventure. We could write a whole book just about the search for art for the 2024 show. What happens to artists in general? Because it’s not only women artists—only a small number of artists actually earn a living through their art or make it to the top.

Susan

You were visionaries in a lot of ways.

Diane

No, no stop right there. We were not visionaries. We were visionaries to pick the curators who picked the show.

If you look at the show at Moore, it’s our exhibition about them [the 1974 artists], but now it’s partnered with the show that Gabrielle Lavin Suzenski curated, and that one includes LGBTQ, non-identified, BIPOC, and non-binary artists. Judy is moderating a panel at Moore College of Art and Design centered on the artists in (re)FOCUS: Then and Now. Participants include me and Joyce Kozloff, Barbara Zucker, Wit Lopez, Isa Matisse, and Cynthia Carlson.

Judy

If you look at all of the exhibitions in (re)FOCUS, you’ll see that if not the majority, close to the majority, are actually BIPOC or non-binary artists.

Diane

I agree. I’m very proud of that. And because that’s what it’s all about. It’s taking the past, bringing it up to the present and introducing the present to the past.

Susan

Because, of course, one of the criticisms of the women’s movement and the women’s art movement was that it was middle class white women.

Judy

And that’s wrong. There were BIPOC artists, art historians, curators. That’s going to be discussed in my book, because, as Kimberly Camp said to me a few months ago, “People say we weren’t there, but we were there.” It’s one of the myths.

Diane

There was a lot of resistance to Black women in New York, with the women’s movement politically. But Judy’s right. If you look at the art part of the movement and the artists, they were there. My God! I just went to a lecture, you know, with Leslie King Hammond and Lowery Stokes Simms. They were active in the College Art Association and the women’s movement from the get-go.

Judy

Barbara Chase-Riboud was in the 1974 show. We’re showing a print of hers that was done at the Brandywine Workshop and Archives. https://brandywineworkshopandarchives.org/ Ruth Fine is curating a show of Brandywine women artists for (re)FOCUS. It’s a who’s who of BIPOC women artists. Diane often says we need to remind people of what women artists and art historians have contributed to the mainstream of art because the art practice of today, including art history, is completely different from what it was 50 years ago—and that’s thanks to the Feminist Art Movement and people have forgotten. It’s just like what happens to women artists who may be famous in their lifetimes but then they disappear after they die. People need to be reminded not just of the artists but also of the ideas that women have introduced.

That’s a little bit of what has happened. So much of art practice and art history today has changed because of the feminist art movement. [(re)FOCUS] reminds people of the importance and impact of women artists but It’s also a celebration of 50 years of feminist art. That’s amazing. A continuous development from a small group and how it spread out and how feminist artists introduced innovations that have become embedded in contemporary art practice—things like use of video, repetition, and decoration.

Susan

Finally, what are some of the highlights you would like to point out?

Diane

We’re having 10 billboards around the whole city, and that’s being sponsored by Mural Arts, and it’s being curated by a young Black curator Noah Smalls. We are focusing on the Colored Girls Museum. Imani Roach wrote about the museum and interviewed its founder Vashti Dubois for the catalog.

Susan

I see there is another public art project, The Artfront Partnership, curated by Marsha Moss, under the sponsorship of Philadelphia Sculptors. They commissioned artists with a feminist perspective to transform vacant, dark storefronts into illuminated art spaces.

Judy

There are panels. One will be at the Philadelphia Museum of Art connected to the Mary Cassat show in May near the end of (re)FOCUS.

Susan

Thank you both so much for this discussion. I look forward to attending as many of the events and exhibitions as possible!

EDITOR’S NOTE:

We’ve been writing about Judy Brodsky since 2007 and Diane Burko since 2003. There’s a lot more.