The newest exhibition at Twelve Gates Arts, whose mission is to amplify contemporary art from South to West Asia, is an immersive, psychedelic installation titled Alhamdu | Muslim Futurism. Conscious of the nuanced, weighted experience of being a Muslim in the U.S. diaspora today the exhibit invites the viewer to call and answer, again and again, what they envision as Islamic Futurism. Through this guest curation, a single participant is invited to fill out a questionnaire via a QR code as they enter the gallery space and then stand in a taped-off square on the floor to face a projection on three blowing curtains. Those are the participant’s only two prompts, and the only question they have to answer on the QR code is “What would you like to contribute to a Muslim future?” The rest of what they gather from this community collaboration with the MIPSTERZ collective can be as variegated as the morphing, exuberant colors on the screen in front of them.

The name MIPSTERZ is a stylized portmanteau of “Muslim” and “hipsters”. Alhamdu | Muslim Futurism is a project by MIPSTERZ involving different video exhibits and public programs across the country. The collective, comprised of independent Muslim creatives in the U.S., works to produce culturally fluid and radically socially conscious art works and events with other arts organization, including eminent institutions like The Shed and Duke University in the past.

This joint effort is dynamic and considers the current and historic issues of Islamophobia, anti-blackness, xenophobia, imperialism, and racism affecting both the Zeitgeist and material conditions of displaced Muslims. The video installation – titled “The Mirage,” meaning “praise be to God” – is credited to Shimul Chowdhury, Abbas Rattani, and Yusuf Siddiq from MIPSTERZ.

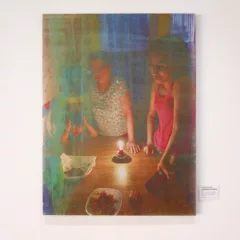

As soon as the participant is invited to stand in the designated square, they are enveloped with a pulsing, meditative frequency in an backing ambient track in front of a looping film. Characters in the videos, dressed in a color palette of teals, prussian blues, lilacs, plums, fuschias, browns, and golds, peer over their shoulders and make eye contact with the viewer. Like twisting a kaleidoscope with two hands and forming an immeasurable amount of geometric shapes out of the same reorganized visual properties, the film multiplies, fractures, and swirls in a diamond-shaped border around the videos main protagonists. A group of women wearing vibrant, cool-toned hijabs are split and the image changes into the next scene where a group of Muslims gather near the center of the lens, sometimes leaning against each other or the camera panning to details of their accessories, before the scene collapses into the next image. In between some of these scenes, an Arabic text with its English transcription is superimposed on the last visual. Through these projections, the viewer is invited to partake in an inquiry of Islamic futurism through timelessness, fashion, and the extent of community participation.

The video is evocative of time and aging across generations because to seek the shapes of a future is to excavate a past, per many ancestor devotional cultures from East and West Africa to West and South Asia. The film zooms in on many glimpses of “crows’ feet” on a kohl-rimmed eye followed by a younger eye not relaxed into these many gathered lines. Community elders in the film wear heart-rimmed sunglasses and trade glances with community members next to them who are decades younger while they both sport the most sophisticated cuts of salwar kameezes, the pants and tunic ensemble with scarf popular in contemporary South Asian fashion.

These visuals emphasize the importance of generational participation because of its age inclusion and juxtapositions. With elder Muslims still here seeing their futures as their community, an extension of their dreams and fantasies. Three of the projected transcribed Arabic phrases solidify this message: “time doesn’t change, time rewards,” “the dreamers never get old,” “everyone you meet has something to teach you.” These messages are the nexus of this video’s imagery on age and looking toward history to learn about the future. Time rewards community and culture-keepers with knowledge; dreamers can continue to paint their dreamscapes, and lessons exist everywhere from the past to present. After all, time is non-linear, just like distortions are non-linear; and just like participation, piety, and cultural allegiance are non-linear. These details are a part of the video’s storytelling, viewed cyclically like time.

The fashion in this video is also a statement on timeliness and where Muslims fall canonically, through design and generations. Fashion, after all, is an art form in itself based on design and textile crafts sometimes reduced from its artistic merit due to a culture of commodification and consumption. The figures in the videos model salwar lameezes, shaylas, hijabs, boubous, caftans, fezes, keffiyehs, ornate gold rings, and turquoise statement jewelry pieces. The outfits take a sophisticated twist on the clothing and styles from a broad range of cultures from the Asian and African continents with detailed beaded and embroidered work over satiny textures that reflect popular influence from both metropoles of their heritage.

The installation’s blowing curtains assist in the storytelling. On close inspection, as the participant is allowed to leave their square of floor space, as most displaced Muslims are metaphorically forced to leave their space, the texture is a synthetic waffle-print translucent fabric. From afar, the curtains look like saris blowing in a window or the ends of a hijab in the wind. The effect is dreamlike and ethereal, and as the text is projected through layers as the first of the three curtains is placed in front of the other two curtains extending out to the side, the images and words are further warped to produce a second image that bears two faded exposures to the original image. Projection on large scrims of fabric is a unique medium, unlike a video installation on a TV monitor, as it fills the entirety of a room. As the participant wanders the room, the image also becomes projected on their bodies as they engage with the physical materials in front of them. The curtains behave like a veil, and through the veil the participant can see the depth of the phrases referencing time reinterpreted, re-evoked, and remixed through many generations much like someone might engage with the complexity of their own religion with what the world projects on them. The participant in this exhibit is as much of a part of this community, with what they bring being who they are innately, as they too can become a part of this exhibit.

However, as conversations evolve and we discuss evolution, distortion, exclusion, reintegration, and reinterpretation in community, this video’s attempt of provoking conversation – whether in providing more prolific questions or answers – is one decade late because of its misunderstandings and the lack of nuances needing to evolve. I think about what subversive art means in the post-Refinery29, post-Tumblr interface art era with beautiful people wearing beautiful clothes and how valuable immigrant nostalgia is in factoring in how we interpret community. The questionnaire seems incohesive with the rest of the exhibit, with some of the potential answers to the question being locked into words with no nuance: “obstacles”, “knowledge”, “service”, and “skepticism”.

The projected video provokes many aesthetic sensations and contemplation rather than being “provocative”. This exhibit is wonderful for experiencing the stylized fashion history and examples of Muslim joy across generations that the original artistic statement does not place much emphasis on. Nonetheless the exhibit is worth visiting in spite of the participatory questions and answers.

Alhamdu | Muslim Futurism is on view until Saturday, February 24th at Twelve Gates Arts, 106 N. 2nd St.. You can visit the gallery space Thursday-Saturday from 11am-5pm.