In the group show organized by Rami George at TILT Institute for the Contemporary Image, found images from George’s “Untitled (minor details) are the catalysts for collaborative visual translations by six invited artists. minor details features work in various mediums and styles.

As a multidisciplinary artist who often works with archival objects, George (they/them) created “Untitled (minor details),” a poster-size photographic collage that is a reflection on queer domesticity and intimate moments of the mundane, from several sources including candid snapshots of their family photos, a photograph they created themself, and collected photos of anonymous lives over the decades, found in thrift stores and flea markets, including a few key erotic photographs – sourced from shops in San Francisco.

The six artists that George selected each interpreted “Untitled (minor details)” and used the photographs as inspiration or directly incorporated the images into their work.

The ritualized experimental video, “Napping on a cloudy day,” by Alina Wang (she/her) is captivating with its calm process of repetition. The single-channel diptych is set across from a “prop” that is the star of the video, namely, a cyanotype-printed pillowcase mounted on the wall. In the video, we see Wang on the right half of the screen sleeping on a cyanotype-dyed pillowcase covering a pillow, a white quilt up to her chin. The pillowcase is being exposed by the sunlight: she is making a cyanotype of herself imprinted on the pillow. Wang remains entirely still throughout the duration of the film (10 minutes and 37 seconds), but for the soft rise and fall of her chest. The left half of the diptych video screen shows an impeccably white bathtub, and Wang’s disembodied hands begin to wash the now exposed pillowcase in a rubber basin, scrunching, rinsing, squeezing it, and by doing so developing the image. She then dumps the water, refills the basin. Wang repeats this several times, periodically she unfolds the pillowcase and we see a brilliant tie dye of Prussian blue. “Napping on a cloudy day” acts as a quiet study on dormancy, time, and domesticity, the process of cyanotype represents what develops beneath the surface, a movement within stillness. As the act of sleeping becomes the negative imprinted on the pillowcase, Wang inserts herself into the art through this experimental process to make the temporary stasis of sleep a permanent design.

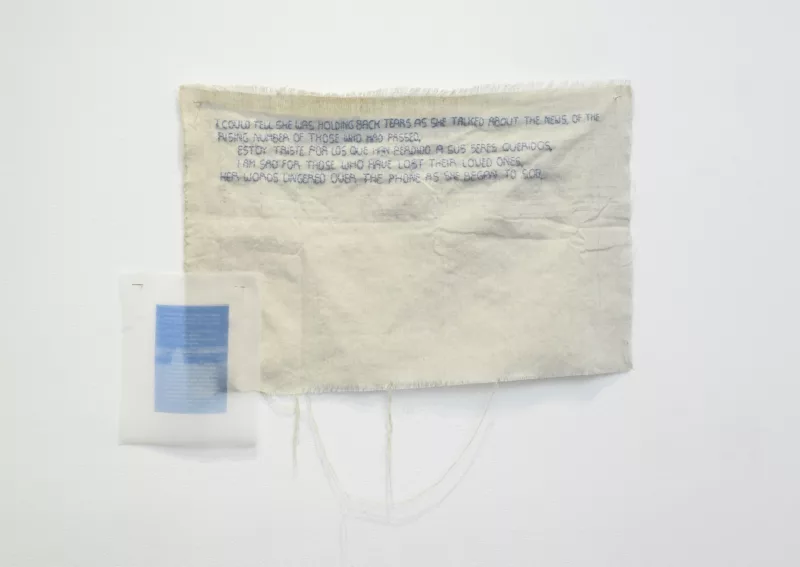

Also striking are Steph Garcia’s (she/her/ella) tapestries; in her piece, “Un Día,” a sheet of canvas hangs with embroidered text consisting of the first few lines of a poem. Beside it, a smaller sheer fabric has a blue, digital photograph of the entire poem’s transcript printed on. The beginning of the poem reads, “I could tell she was holding back tears as she talked about the news of the rising number of those who had passed.” This poem – written by the artist – reflects on a phone conversation Garcia had with her mother, and it conveys layers of grief. The poem shows Garcia’s mother’s grief over the loss of life during COVID-19 and Garcia’s own grief around the separation and distance from her mother, who lives in California, contrasted by the hope that they will one day be reunited. The poem is also partly inspired by Rebecca Solnit’s book A Field Guide to Getting Lost. The embroidered text is boxy and uniform on bulky canvas, in contrast, the crisp text on the blue digital photograph gives a lithe appearance. This contrast between angularity and softness, and between light and density, gives context to the tension felt in the mother and daughter’s parallel yet separate experiences. The canvas’s fraying and gathering at the bottom add a tangible materiality of disintegration and enmeshment.

A participatory conceptual piece, “totem,” by Nick Moncy (he/they) appears to be about archival creation. On a wall screen, part of the text reads, “what is ‘sacred’ in your world?” Viewers are encouraged to use a QR code to access and print out (at a small printer installed nearby) their “icons” and attach them to the silver and white refrigerator doors stacked and lined up, already adorned with printed images (such as The Cure bandmates, the night sky, art supplies), drawings, and post-it notes. Small pieces of moss creep through the crevices of the no longer functional appliance doors. Moncy reclaims iconography that graces the average refrigerator as extraordinary, and brings attention to a universal object that upholds our achievements, sentimental items, and small reminders. “totem” acts as a vestige of the domestic, the ordinary, the divine.

Connie Yu’s (they/them) burnt orange risograph “Rub” series also compelled my attention, a partial imprint of floorboards on hanging newsprint, a simple but elegant abstraction of interior space often overlooked. In particular, the negative space in “Rub” is very persuasive, giving a ghostly effect. MAP (they/them) also utilizes negative space effectively in their piece, “Weft,” which showcases a loom with an unfinished tapestry of twine interwoven with five images from “Untitled (minor details)” transferred onto various fabrics. Piercings peek through the tapestry as a playfully and overtly queer homage. Most of M Slater’s (they/he) work involves magazine cutouts of a young Leonardo DiCaprio, his face covered by various white-painted framing beams made with paper pulp and joint compound, that also seem to be propping up his picture on the walls.

Read as a sardonic take on pop culture, Slater’s work diverts thematically and tonally from the rest of the exhibition. However, this discrepancy emphasizes the creativity of minor details‘s concept; it highlights the interpretative nature of the exhibition, and allows the artists to be a directive part of the curatorial process. minor details breaks traditional barriers between curator and artist, and makes the gallery a space of collaboration.

minor details is on view at TILT Institute until March 23, 2024.