If you’re wondering how to define the concept of “liberty,” the artist and wry provocateur, Ai Weiwei, has an answer: “Liberty is about our rights to question everything.” That quote is on the website of the National Liberty Museum, where a current exhibition of large-scale works by seven artists fills multiple floors. The artists come from varied backgrounds and ask probing questions about the America of yesterday, today, and tomorrow. The works in the show are vastly different from each other but share a sophisticated blend of rich artistic execution and personalized political audacity. This is a great addition to the summer’s exhibition lineup.

Credit for assembling the artists, whose work is both visually and politically engaging, goes to the curators Elaine Crivelli and Leslie Kaufman of the non-profit group Philadelphia Sculptors. Planning started five years ago during widespread social unrest in the US. The curators had questions: What do artists from diverse cultural, ethnic and geographic backgrounds think America stands for? How would they define democracy? Why do some people benefit from the ideals of democracy and others don’t? While looking at artists, they were also looking for venues. They found a supportive partner in the intriguing and evolving National Liberty Museum. I can’t think of a better place for this work – a wonderful, quirky institution with an admirable mission and vision to build “a society that values freedom of thought, civil discourse, respect for all people and the essential pursuit of liberty.”

One particularly endearing aspect of the museum, created by Irving Borowsky and opened in 2000, is its affinity for sculpture. Yes, yes, there’s a replica of the Liberty Bell near the entrance, but what I wasn’t expecting was the large number of glass sculptures and installation works that accompany a permanent exhibit called “Heroes of Liberty from Around the World.” Or the site-specific 21-foot glass sculpture titled “The Flame of Liberty” by Dale Chihuly, that spans two floors through a circular opening. Commissioned in 1998 by Borowsky – https://www.libertymuseum.org/about-us/our-story/ an activist philanthropist and glass art collector who at the time was fundraising for his envisioned National Liberty Museum, “The Flame of Liberty” was the showpiece of the museum, which held annual glass art auctions to support glass art practitioners.

Not every institution would be comfortable cutting a large hole in a floor. And not every institution goes out of its way to foster design literacy as a tool for change. An impressive exhibition on the lower level called “Project Liberty: A Design Challenge” is a primer on the methodology and stages of the human-centered approach to solving problems called Design Thinking. In plain but engaging text and visuals, visitors, especially kids, are introduced to the different stages that make up Design Thinking, then they are given real world problems to practice their skills of empathy, definition, ideation, prototyping and testing on.

I admire politically focused work and programs that don’t simply complain and treat issues as subject matter to be depicted and passively consumed. What I saw in the “In Pursuit” and “Project Liberty” exhibitions are types of behavioral modeling with ambitions to help viewers understand a range of complex issues. I was particularly struck by the work of Artur Silva. His installation, “All Threats Came in Waves,” first hooked me with its comical juxtapositions. That feeling of delight and curiosity quickly gave way to a gut-punch of personal and national embarrassment.

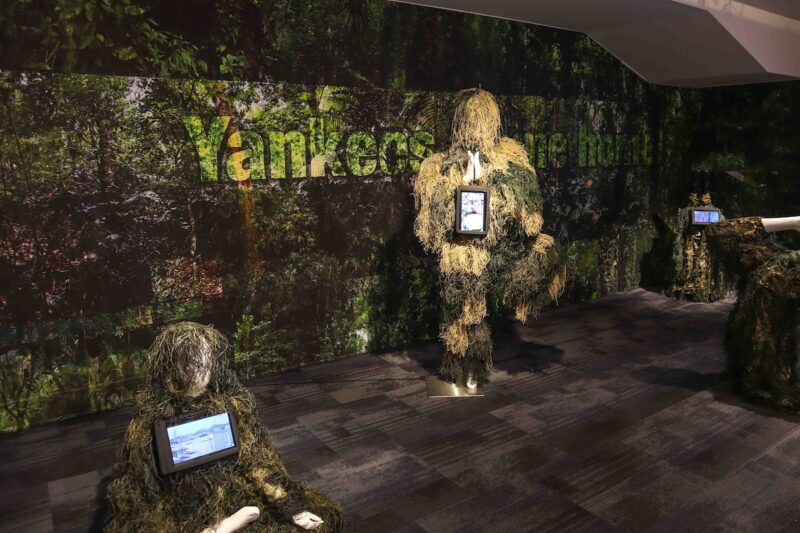

In Silva’s multimedia installation, a photographic image of a dense jungle with text reading, “Yankees, come home” is the backdrop for a gathering of bizarrely attired and posed mannequins. The figures are dressed in ghillie suits, which are camouflage patterned outfits covered with tangled masses of green or tan raffia-like fibers. They are used by the military for concealment. I’ve never seen one in person, let alone many adorning mannequins frozen in yogic postures and emitting images from the small monitors lodged in their bellies.

A larger monitor on the far wall shows footage of life in Brazil and explains the impact on the country of yet another ill-conceived, meddlesome part of American history that I wasn’t familiar with. The US, at President Kennedy’s direction, colluded to overthrow the democratically elected president of Brazil, João Goulart in 1964. The resulting military dictatorship lasted for over 20 years. Silva grew up during that period and lived with the consequences of the brutal and restrictive regime, while also being bombarded with waves of propaganda through TV shows like “I Dream of Jeannie” and “The A Team” that showed the US military in a fun and flattering light. I walked away from the installation knowing more than when I went in, and thinking about how I had watched those same shows growing up and how incomplete my public school education was.

I usually take the stairs in smaller museums but that day I took the elevator. The elevator’s “On View Now” list includes a warning: “PLEASE BE AWARE you may hear screaming.” The sign goes on to explain that there is a participatory artwork on the 3rd floor. That would be “Neon American Anthem,” by the Alaska-based Tlingít and Unangax̂ artist Nicholas Galanin. In a very dark room, large blue neon letters in all caps and a serif font spell a chilling message: “I’VE COMPOSED A NEW AMERICAN ANTHEM: TAKE A KNEE AND SCREAM UNTIL YOU CAN’T BREATHE.” Square rubber mats are thoughtfully placed a few feet from each other. The jumbotron-size neon letters referencing football’s Colin Kapernik’s “taking a knee” in protest during the singing of the American anthem, and the rubber exercise mats recall spectator sports events. We think of the last words of Eric Garner, the individual, but also of the subjugation of indigenous peoples and systemic racism. It’s a destabilizing work, beautifully executed yet woeful in its origin. What can one person do when peoples’ lives and liberties are lost? The artist invites us to communally share in shattering the silence around shameful histories. The piece could tip into obviousness, but it achieves a monumentality through its clarity and simplicity. I found out later that this is the third iteration. The previous versions were red and white.

Aram Han Sifuentes’s work also invites viewer participation. In her large fabric-based piece, “Memorial to Gun Violence: An AR-15 was Destroyed to Make this For You,” the Korean American artist created a large, circular enclosure from fabric panels dyed with iron pigment derived from dissolving an assault rifle. The circular structure is suspended from the ceiling, and handwritten notes are pinned to the exterior. It’s not clear what is going on until you read the signage and realize how the splotchy pinkish fabric was dyed. The artist provides cards and a pen with ink made from the dissolved firearm for visitors to write down their thoughts about gun violence.

I found this piece off-putting. The color of the fabric has a sickly feel and completely undermines what should be an inviting space to enter. When you do enter it, it’s a let-down. Something feels missing. Perhaps that’s another point that’s being made. Outside of the piece are beautiful and haunting life-size figural works on paper. Again, using residue to communicate, Han Sifuentes and her young daughter’s bodies are indicated using oil and charcoal to print partial impressions of their bodies in the series titled, “I Often Think About How I’ll Stop Bullets from Entering Your Body.”

In the same room, the Latino sculptor Angel Cabrales, who grew up in the border towns of El Paso, TX, and Juarez, Mexico, provides a wild ride through the possible experiences and fates of migrants by creating a 3D board game that is visually and conceptually complex. Cabrales’s work, “In Pursuit of Happiness: A Venture in Migration” shares elements of Hasbro’s “The Game of Life,” but Cabrales puts users in the shoes of players like “Unaccompanied Minor,” “Dreamer,” “International Student.” Each player or role has a different set of rules. It’s funny and heart wrenching. I wish every school had this game. A second piece surrounds the game. A video with images of actual people is animated to disguise them as they talk about their migration experiences.

Arghavan Khosravi, who was born in Iran and now lives in the US, creates beautifully rendered paintings in multiple panels each holding a part of an image and together making a broken puzzle of an image. The pieces recall Persian miniatures, and subvert the tradition through scale, image disruption and coded symbols. The artist collages and blends images and objects to hint at the complexity and tension she and other women face when their liberty exists only in private. There is a theatrical aspect to the work that underscores the roles women in repressive societies must take on.

Also theatrical – although it is a jarring transition from Khosravi’s lush and considered works – is Marisa Williamson’s sprawling, gritty installation, “Seedbed V,” a “ruin” according to the artist’s statement. The piece (see top image) is part of a series of works based on Williamson’s performances focused on the historical figure, Sally Hemmings, Thomas Jefferson’s slave and the mother to a number of his children. Williamson wonders “what is an appropriate monument to a foremother?” She approaches the question collaboratively, working with her students on the piece. A video projection plays in the background, showing an encampment indicated by a fabric ground cover. A shopping cart filled with collections of cards and papers anchors one corner. What looks like a papier mâché mummy is laid out on astroturf. The Artist Statement lists bottles of dried tears as elements in the work. It is hard to look at and hard to look away from.

I’m ending with the first work you see when you enter the museum. Just past the front desk is Anila Quayyum Agha’s “This is Not a Refuge.” A dazzler, literally and conceptually, the central object is a scaled-up version of an archetypal house, but the walls and roof are not solid planes. They are pierced with a pattern of swirling leaves and flowers: A beautiful cage. A blindingly bright light in the center of the closed space projects overlapping shadows on the walls and ceilings. There is so much going on in this brilliant, yet simple work. We are excluded from physically entering the structure, yet we are enveloped by its radiance. You see both a simple shape and infinite patterns. An audio component plays in the background. You hear a variety of stories from immigrants and refugees describing their experiences of coming to the United States. I listened and looked and wished for a bench.

In Pursuit: Artists’ Perspectives on a Nation is on view at the National Liberty Museum, 321 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106 from May 10th through October 28, 2024.

Read more articles by Sharon Garbe on Artblog.