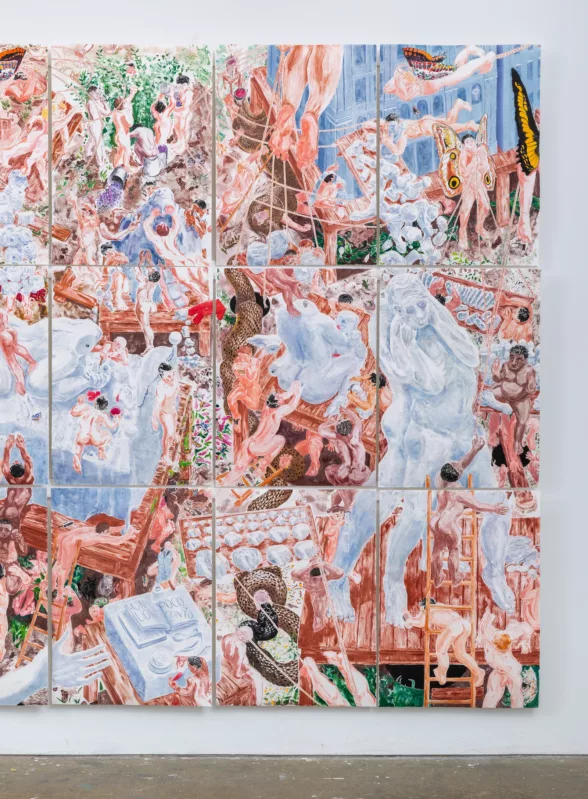

A chapel-ing of a churning-making on a 27-panel monotype depicts the building of an orgiastic sculpture park in an ode to the history of art history. It is the uncentered center of “Becoming Hole” an exhibition of new work by Todd Stong at Peep Projects.

The result of both careful planning and gestural marking creates a multi-timeline narrative of the building, by hundreds of unclothed workers, of a sculpture park of which the sculptures will tell the tale of Johann Joachim Winckelmann‘s murder and his murderer’s execution. A riotous contemplation on art, labor, history, faggotry, with a pair of small twining cats as guides throughout.

There is so much here to discuss, delicious and disgusting, fantastical and historical. Twenty beautiful graphite drawings in this show ought not to be forgotten, however, my interest and aim is to dive deep into the monotypes. As the viewer is directly implied in the work, I will implore you to walk with me as we build an understanding of this work together.

Let’s begin slowly and simply in the work of a moment. The present tense of when the ink is applied to paper. The creation of a monotype – hidden behind each, a week of painting onto plexiglass, months of planning, and years of practice. It is an interesting kind of planner that is willing to risk all this time on a one-shot image, an example of printerly daring and intelligence. Stong described how so much of it could go wrong in an instant – and would have to be done again. Some of the potential threat to the legibility of the image comes through (though is never seen), as well as the intuitive focus of a monotype artist, following the rhythm of applied pressure and pull.

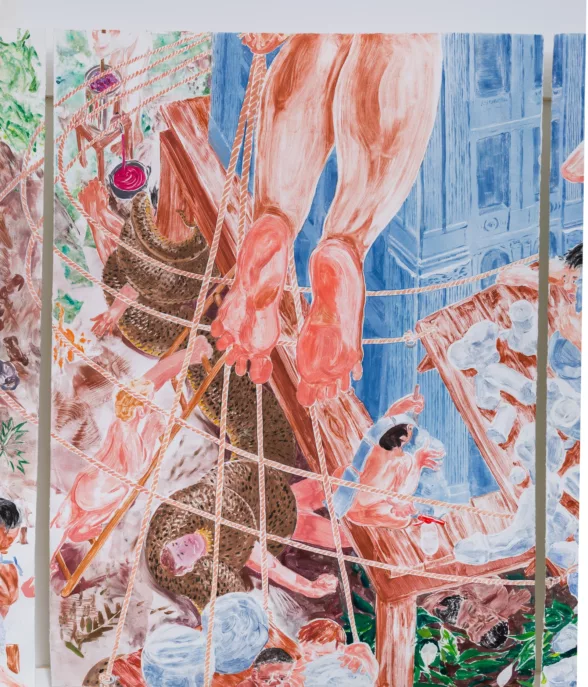

The prints themselves are a record of applied contact, ink to plexiglass, plexiglass to paper. The image itself is full of represented contact as well, skin on skin, on snow, on wood, on scales, on rope. A misalignment could distort the image or even cause one of the many busy nude workers to tumble off a raised platform into a dense and infinite hole. Part of me is curious to see these cursed pages (every artist has them), but also to go forward in understanding that each of these monotypes captured for us has infinity behind them – an impossible intersection of times and spaces and fantasies and realities.

Now we’re going beyond the present, into the fracturing of time itself. The monotype is made of many paper panels hung together, with a slight margin between them. Not so much patchwork as “worked” patches, breaking in and out of time to create a whole image – which contains its own fracturing. We are shown some signs of the passage of time and the impression of past events; tracks made by a gate opening, mud, snake skins, dead/dying bodies, lunch, a skeleton, and the workers relieving themselves in a multitude of ways.

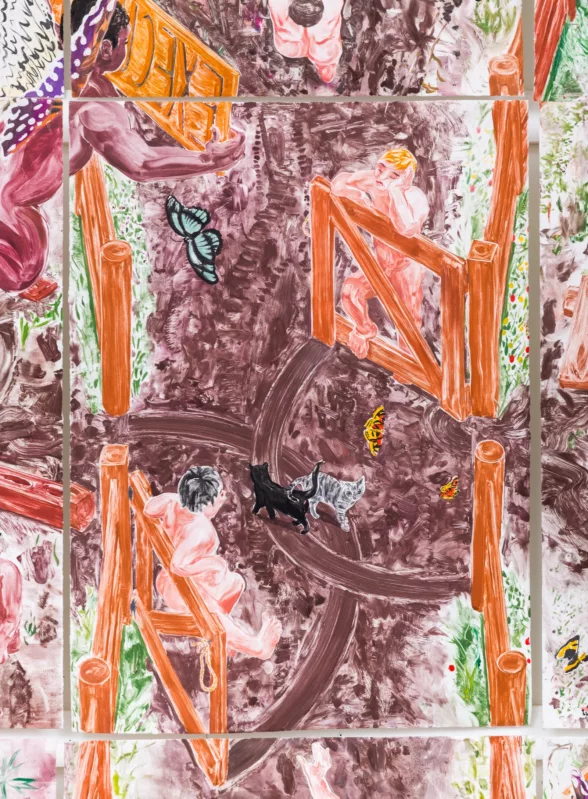

The tidy rectangular gallery at Peep doesn’t allow for a stepping back to view the whole image, instead, we must vibrate within feet of the panels, adding up the image ourselves. The pages of the story are splayed and the viewer is involved in the choose-your-own-adventure picture book, trying to add up a singular story out of a tangled plot of cause and effect. If a viewer is spending time with each panel they will eventually begin to see two figures repeating – seemingly able to travel anywhere on the picture plane, sneaking into multiple panels when the viewer is looking elsewhere, perhaps at a cock made of snow, or the choked purple face of one of the unfortunate workers killed by a gigantic snake that roams the borders.

I’m speaking of course of the pair of cats, one tabby and one black, they twine as a central (ish) element of the piece(s). They are the key to a small piece of information – that this image is not whole, it is not an illusion of one captured moment in time, but many. The gutters of space between the image, seams of our reality that trace a grid throughout the piece animate the image, moving quickly and invisibly to flip through pages in the pictures-world’s time.

The very essence of cathood, wise and knowing, flippant and carnivorous, violent and playful, living not in recognition of logic or hierarchy but instead a kind of amoral exploration I believe is key to the understanding of this piece.

Now we’ll move into the depiction of the physical, space. The whole composite dodges the center by one row. What appears to be the center at first, a thoroughfare that appears to be temporarily void amid deliveries, is in fact left of. Stong cites eccentric ( as in, not centered) composition as a political choice, seeing central composition as upholding Western notions of reason, power, logic, and whiteness.

Additionally, the order of the events depicted in the sculptures ought to be read right to left, the murder of Winklemann before the execution of his murderer, again choices made in mild opposition to Western reading. Our position as viewers on the ground looking up and above into the work makes us climb into it perspectively. As discussed in The Power of the Center by Rudolf Arnheim, “This means that merely by looking at a picture, the viewer gives it more depth than the structure of the work itself contributes.” (p. 48) This further jumbles us in time as the appearance of events in the background and foreground of the piece imply a steady progression in time, but with an image intent on climbing upwards, where are we? Where is now?

The world is depicted with laws of gravity, “…we acknowledge the eccentric power of gravity that pulls us down. In response, we struggle to liberate ourselves from the coercion of our earth-bound condition and to rise – with height as an eccentric objective, the explicit target of our striving.” (The Power of Center, Arnheim, 7). We can see this in ladders, ropes being used to pull artwork erect, platforms being held up by beleaguered butterfly angels, workers holding up the weight of sculptures, butterflies in flight, and deep dark holes.

The holes are flat and dense and all other marks are quite open and porous, where do they go? They are titular images of the show, being used as toilets and trash cans, as well as graves and moments of wonder. Their mystery is a large period stopping us from finishing a full sentence in which we claim to hold the entire work within. They in themselves are a concentration of the frantic mystery logic and rules that operate the world of the piece, under which there seem to be frequent and dire consequences.

Let’s discuss the sensory while we move closer and closer to the subject/s represented in the work itself. Almost every bodily projectile or refuse is present here or at least alluded to. The 200 nude workers while scrambling to build a sculpture park still manage to sneak to meet almost every need being attended, hunger, sex, rest, defecation, and death. Some of the most violent and volatile imagery is represented through the in-progress sculptures. While snowy in color they retain a kind of purity bestowed on Greco-Roman sculptures by Winkelmann himself, however, they depict his murder by a likely sexual companion, and that murderer’s gruesome execution. On the bottom, an assistant in charge of detail is adding red pigment into the sculptures, meant to signify blood. A deposit of extra-sensory information is given by the object of the prints themselves. With a space behind each of the prints distanced from the wall, I imagine cum and mud and blood and piss and shit smeared through the fibers and holes into the backs of the papers. If the backside of this web browser, floating in the unreality of the screen is a flat grey with a faint electric taste on the tongue, and the back of Monet’s “Le Dejeuner Sur l’herbe” is a perfumed must of sun-spoiled wine, pollen, and oil paint, and the back of Bruegel the Elder’s “The Harvesters” smells of heat and hay and the feeling of being “dead tired” while chewing a crust of bread, then surely there is a back to this world’s frantic episodes.

In Stong and I’s discussion about the work I brought up a comparison to frescoes in Rome, I immediately made connections to “The Last Judgment“ by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel. Piles of bodies, flying to salvation, being held to earth and damned, having a thousand small interactions on a huge field of blue and white sky. Stong revealed that his time studying on the Temple Rome campus in 2022 was hugely impactful and informative for his work. I also observed a connection more broadly and thematically to the images and content in depictions of the stations of the cross.

The Stations of the Cross is a series of fourteen pictures or carvings representing an order of events in Jesus’s progress towards his crucifixion and burial. In these depictions, each element that is located in time is not seen individually in sequence, but typically all at once. One is meant to understand every event cumulatively. The beginning is made severe by the end, and each step is more and more brutal knowing it will always “end” the same way. Christ is constantly marching towards death and also already dead, for it to function as a moral device it must be perpetual, not a concrete event in the past.

We see the murder of the art historian Winckelmann who at the time of his death was a papal antiquarian, step by step being erected by these busy stacks of working men, each moment of his death and the death of his murderer Francesco Arcangeli, happening all at once, always. Just as these men and cats and snakes and sculptures are suspended in perpetuity, infinitely working, dying, and sucking each other off.

There is fear, frenzy, focus, procrastination, preparation, disengagement, distraction, and even death in the faces and bodies depicted of the workers in the piece, every emotional and physical state of an artist while making an artwork. While viewing we are looking in interruption. The building of a sculpture park mid-project by a hard-working mass of putti-like nude men. We see them at all stages of making, sketching, carving, and assembling massive sculptures. We also see them lunching, fucking, sucking, napping, dying, and pissing. It is a chaotic workplace filled with horny men, bottomless holes, and murderous snakes.

One can see an artist’s (who also works as an artist’s assistant) rueful understanding of the chaotic inchoate labor of the artist’s studio. Where interpersonal boundaries shift and search wetly as materials dry or are cut, deadlines are approaching or lunch break is delayed.

There is an unseen god/boss implied in this work – “I guess it’s me.” Stong told me, with recognition. Do we command the creatures of our creation? The little workers scramble about the tilted perspective of the landscape, they seem bent on executing the orders of their boss in a single workday. The work isn’t done but the viewer is here! It isn’t done but, they are working hard. Don’t they deserve a little break? Some of the men help themselves to naps and sandwiches and one another’s bodies. I recognize the special kind of disoriented inertia that the overworked body moves through while repeatedly being driven towards pointless ends. The mischievous play between workers resulting from surviving the brutality of labor is reminiscent of the equally “ideal” masculine forms (and their activities) illustrated in Tom of Finland’s body of work. The sculptures are made out of snow – does that mean they melt and are built daily? Trying again and again to get these historical figures right, to get them into being from the past, and then to melt away and become passed again.

I wondered if any of the figures depicted would eventually notice death underfoot and around the margins – there seems to be one in the lower corner, perhaps a whistleblower. Drawing attention to the artful curlicues of men strangled by a snake about to have a very large meal. This man near the edge of the page reminds me of the plants and demons scrolling in the margins of illuminated manuscripts, whose actions ought not to be pointed out by the central text and are not meant to create consequences for the main story. He points to the corner, to the edge of the image dramatically and distinctly, what other horrors do the edges of the paper hide? A stern invitation, to look beyond one of the multiple tiers of organization in Stong’s sculpture park.

Stong let me know that he intends to further explore more lives in his artwork, “learning through living through other people.” I look eagerly towards the next gay foray into lapsed events, which presents the question of history; who’s life is worthy of note? Who will be remembered? Who will be forgotten?

“Todd Stong: Becoming Hole,” at Peep Projects through July 27, 2024. (727) 204-2853 peepprojectsphilly@gmail.com

Read more articles on Artblog by Lane Timothy Speidel.