Some came for the music, others for the art; but I suspect the majority of the audience came for a glimpse of the evocative decay of the Royal Theater’s once splendid interior; the theater at 1524 South St. was built in 1920 when movie houses were still palaces, but has been closed for the past 40 years.

The Royal’s current condition can best be judged by the fact that the audience was required to don bright, blue hard hats provided by The Network for New Music which sponsored the program in conjunction with Hidden Philadelphia . The last time I wore a hard hat was on an early visit to Eastern State Penitentiary before its fate had been determined and the site had been made safe for visitors (although they still require a release).

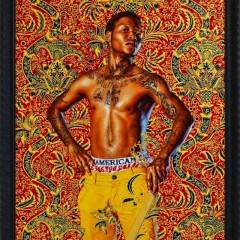

The Royal was Philadelphia’s first black-run theater, set in the middle of what was then a vibrant African-American neighborhood. The interior reflected the ambition of its name: the stage flanked by huge gilded columns, a chandelier (long gone) on the ceiling and walls decorated with stenciled patterns. It was an entertainment center for the community featuring live acts including Fats Waller and Bessie Smith as well as movies. I found myself sitting next to Jessie Frisby who owns Jessie’s Ladies’ Shop (across the street from the theater) and is president of the neighborhood merchants’ association; she recalled seeing movies at the Royal as a child, and proudly told me she’s included in the mural that’s now on the theater’s facade.

I was there to see the recent video by Anri Sala, an Albanian artist whose video, Intervista (1998) had been one of the high points of the exhibition Archive Fever at the International Center for Photography, New York last year. What I got was an adventurous duet of video with live performance in which the video, The Long Sorrow, was an equal partner.

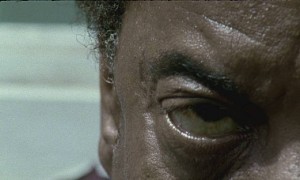

The performer I heard on Thursday was saxaphonist Marshall Allen, an early member of Sun Ra’s Arkestra and Free Jazz pioneer; he’d been given a lifetime achievement award the previous night at the Vision Festival at the Abrons Arts Center in New York’s Lower East Side. On Wednesday the performer was Jemeel Moondoc, the saxaphonist who is in Sala’s video. The video, spare and restrained, focused largely on Jemeel’s face as he played. The camera’s stillness left the music to carry the intensity off which Marshall Allen played.

The Long Sorrow was filmed at one of Berlin’s modern, high-density housing projects and the title comes from the inhabitants’ nickname for the building. It began with a close-up of Jameel’s face seen through a window and only at the end did the camera move back to give a view of the site and reveal the fact that the musician was suspended outside a top-floor window. Projected onto the theater’s side walls the video lost the crispness it would have in a gallery, but the contribution of the recorded musician lamenting the soulessness of his surroundings was as clear as the live musician’s recreation of better days at the Royal. It was a duet of memory, sadness, opposition and perhaps hope; of locations as well as performers. Its intensity blew away any possibility of the romance of ruin accruing to the theater. Instead it emphasized the power of the art and music that was nurtured there in its glory days, and of the neighborhood’s loss.