ArtYard, a contemporary arts center in Frenchtown, NJ, has a history of creative transformation. The main building was once an egg hatchery; the newly constructed arts center now includes several galleries and a theater, all part of a chic interdisciplinary, collaborative campus encompassing several former residences and a former electronics warehouse. A little over an hour from both Philadelphia and New York City, ArtYard is a fitting site for Barrier, an interwoven group exhibition curated by artists Kaitlin Pomerantz and Lucia Thomé that explores shifting boundaries.

Greeting the visitor outdoors, a wooden gate structure by Pallavi Sen invites passage between arbitrary sides. The majority of its boldly painted design is oriented westward towards the Delaware River, a playful reminder of the natural – and easily traversed – division between New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Also facing west is Sandra SK Amoabeng’s upstairs installation, a free-standing, three-paneled screen consisting of soils and dyes on wood that celebrates floral, organic motifs in both form and content. A wide swath of red earth (a path of soil the artist created directly on the floor) connects the painted screen to the window where a planter box of succulents is positioned with the ideal view of the artwork, suggesting a non-anthropocentric hierarchy.

The exhibition as a whole destabilizes perceived divisions – sometime pictorially, like in Matthew Colaizzo’s intricate paintings and drawings, in which modular depictions of building materials, like bricks, cones and barricades, create and deny the illusion of space – and sometimes geographically, as in Ivanco Talevski’s linear explorations of the artist’s two homes, in Philadelphia and Macedonia. Using structured architecture as a mnemonic device, his bold charcoal drawings of remembered, domestic spaces span a four-year period of time, including the pandemic.

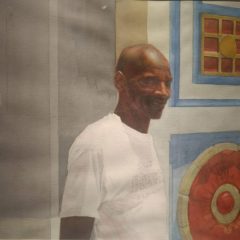

Looking back is a form of a temporal division. A large transparent print, rolled into a cylindrical column, reveals a bright blue sky shining through a tangle of barbed wire. This image was taken by the artist’s mother in 1992 in her home city of Beirut, a cross-generational collaboration by Ghida Dalloul that blurs barriers of time. Naomieh Jovin’s photograph connects via patriarchal lines back to Haiti; a man, who is taking a break from building a wall, is partially obscured by an extended hand dropping a pair of knuckle-bones in the jack-like game of Ossele. The striking image is paired with a gate salvaged from her family home, a signifier of place, memory and human passage – or denial of passage, when hung on a wall.

Diasporic connection is explored through the domestic in an ambitious installation by FORTUNE. Against a vibrant orange, riso-printed backdrop, a faux fireplace mantel displays framed photographs of barriers, taken in the family homelands of each of the artists of the collective: Japan, Thailand and China. The artists–Andra Palchick, Heidi Ratanavanich, and Connie Yu–also offer visitors a triptych of poetic prints to take home, further blurring divisions between exhibition space and lived experience.

Zach Ozma’s takeaway print is shelved with his collection of interrelated and intimate ceramic objects. Created from refuse gathered from Delco’s Darby Creek, the small works fuse and reframe discarded relics (like shards of pots) into new works. The two-sided print both identifies the artifacts and diagrammatically connects concepts of queer ecologies with a poetic, material sensibility, presenting boundaries as potential nodes of connection and transgression.

We are likewise reminded of the non-neutrality of the human-made material in Kristen Neville Taylor’s “Spectral Device.” Constructed from “chemically unstable handmade glass,” the semi-opaque crystalline rectangle stands upright like a window, framed in a metal stand. The veil-like window has an arched portal carved through the center; laser-printed black and white images adorn its surface: an ostrich with its head in the sand, two hands comparing polluted sand, an entrance to a mine. While mysterious, the piece offers a composite visual representation of the ecologically impactful process of glass manufacturing.

Reconnecting materiality to its source, Levester Williams examines extractive practices and systemic racism at the literal bedrock of the nation. A video embedded in a pile of marble chips on the floor loops mesmerizing drone footage of a Maryland quarry, just north of Baltimore. Its stone built the columns of the United States Capitol, the Washington Monument, and countless rowhouse stoops in the Philadelphia and Baltimore region. In the accompanying video and collages, the artist lovingly connects labor back to the black bodies – and lives – that this country has historically devalued.

Nearby, New York-based artist, David L. Johnson presents a collection of architectural plaques forcibly separated from the property they once claimed in a series called “Adverse Possessions.” Displayed on a long plinth on the floor, they form a new line, a delightfully anarchistic reminder of the capitalist underpinning of barriers and its legal implications against shared, public space.

Through critical intervention, human connection, and material collaboration, the artists and curators of Barrier creatively challenge divisions, directly citing (and invoking) 1960s-era icon, philosopher and political activist Angela Davis’s vision: “walls turned sideways are bridges.”

Transparency notes

Cindy Stockton Moore is a Philadelphia based artist and writer who has had the pleasure of working with many of the Barrier artists and curators through The Velocity Fund and Community Supported Art; she has shown with ArtYard at their former location during The Chalkboard Chronicles. On this recent trip, Cindy travelled to the exhibition with artist Erik Ruin and is grateful for his enlivening insight and company. With additional thanks to Mary Smull, her trusted first reader and fellow traveler.